By this time Peregrine was feeling very limp, but he kept his chin up, and said in as even a voice as he could manage: “In that case, sir, I shall have to ask you to have the goodness to wait until next quarter-day, when I shall be able to pay you—not all, but a large part of the sum I owe you.”

The Earl once more looked him over in a way that made the unfortunate Peregrine feel very small, and hot, and uncomfortable. “Perhaps I should have told you—in the character of your guardian—that it is customary to settle your debts of honour at once,” he said gently.

Peregrine flushed, gripped his hands together on his knee, and muttered: “I know.”

“Otherwise,” said the Earl, delicately adjusting one of the folds of his cravat, “you may find yourself obliged to resign from your clubs.”

Peregrine got up suddenly. “You shall have the money by to-morrow morning, Lord Worth,” he said, his voice trembling. “Had I known—had I guessed the attitude you would choose to assume I should have arranged the payment before ever I called on you.”

“Let me make one thing quite plain to you—I am speaking once more as your guardian, Peregrine.—If I find at any time during the next two years that you have visited my friends Howard and Gibbs, or, in fact, any other moneylender, you will return to Yorkshire until you come of age.”

Very white about the mouth, Peregrine stared down at the Earl, and said rather numbly: “What am I to do? What can I do?”

The Earl pointed to the chair. “Sit down.”

Peregrine obeyed, and sat with his eyes fixed anxiously on his guardian’s face.

“Do you quite understand that I mean what I have said? I will neither advance you money for your gaming debts, nor permit you to go to the Jews.”

“Yes, I understand,” said poor Peregrine, wondering what was to become of him.

“Very well then,” said Worth, and picked up the little sheaf of papers, tore them once across, and dropped them into a wastepaper-basket under the dressing-table.

Peregrine’s first emotion at this unexpected action was one of staggering relief. He gave a gasp, and his colour came flooding back. Then he got up quickly, and thrust his hand into the basket. “No!” he said jerkily. “I don’t play and not pay, sir! If you will neither advance me the money nor permit me to obtain it in my own way, keep my notes till I come of age, if you please!”

The Earl’s hand closed over his wrist, and the grip of his slender fingers made Peregrine wince. “Let them fall,” he said quietly.

Peregrine, who had caught up the torn notes, continued to clutch them in his prisoned hand. “I won’t! I lost the money in fair play, and I don’t choose to put myself under such an obligation to you! You are very good—extremely kind, I am sure—but I had rather lose my whole fortune than accept such generosity!”

“Let them fall,” repeated the Earl. “And do not flatter yourself that in destroying the notes I am trying to be kind to you. I do not choose to figure as the man who won over four thousand pounds from his own ward.”

Peregrine said sulkily: “I do not see what that signifies.”

“Then you must be very dull-witted,” returned the Earl. “I should warn you that my patience is by no means inexhaustible. Put those notes down!” He tightened his grip as he spoke. Peregrine drew in his breath sharply, and allowed the crumpled papers to fall back into the basket. Worth let him go. “What was it you wanted to say to me?” he asked calmly.

Peregrine swung over to the window, and stood staring blindly out, one hand fidgeting with the curtain-tassel. His whole pose suggested that he was labouring under a strong sensation of chagrin. The Earl sat and watched him, slight smile in his eyes. After a moment, as Peregrine seemed still to be struggling with himself, he got up and slipped off his dressing-gown, tossing it on to the bed. He strolled over to get his coat, and put it on. Having adjusted it carefully, flicked a speck of dust from his shining Hessians, and scrutinized his appearance critically in the long mirror, he picked up a Sevres snuff-box from his dressing-table, and said: “Come! we will finish this conversation downstairs.”

Peregrine turned reluctantly. “Lord Worth!” he began on a long breath.

“Yes, when we get downstairs,” said the Earl, opening the door.

Peregrine made a stiff little bow, and stood back for him to go first.

The Earl went in his leisurely fashion down the stairs, and led the way into a pleasant library behind the saloon. The butler was just setting a tray bearing glasses and a decanter on the table. He arranged these to his satisfaction, and withdrew, closing the door behind him.

The Earl picked up the decanter, and poured out two glasses of wine. One of them he held out to Peregrine. “Madeira, but if you prefer it I can offer you sherry,” he said.

“Thank you, nothing for me,” said Peregrine, with what he hoped was a fair imitation of his lordship’s own cold dignity.

Apparently it was not. “Don’t be stupid, Peregrine,” said Worth.

Peregrine looked at him for a moment, and then, lowering his gaze, took the glass with a murmured word of thanks, and sat down.

The Earl moved towards a deep chair with earpieces. “And now what is it?” he asked. “I apprehend it to be a matter of some importance, since it sends you looking all over town for me.”

His guardian’s voice being for once free from its usual blighting iciness, Peregrine, who had quite determined to go away without mentioning the business which had brought him, changed his mind, shot a swift, shy look at the Earl, and blurted out: “I want to talk to you on a—on a very delicate subject. In fact, marriage!” He gulped down half the wine in his glass, and took another look at the Earl, this time tinged with defiance.

Worth, however, merely raised his brows. “Whose marriage?” he asked.

“Mine!” said Peregrine.

“Indeed!” Worth twisted the stem of his wineglass between his finger and thumb, idly watching the light on the tawny wine. “It seems a trifle sudden. Who is the lady?”

Peregrine, who had been quite prepared to be met at the outset with a flat refusal to listen to him, took heart at this calm way of receiving the news, and sat forward in his chair. “I daresay you will not know her, sir, though I think you must know her parents, at least by repute.”

The Earl was in the act of raising his glass to his lips, but he lowered it again. “She has parents, then?” he asked, an inflection of surprise in his voice.

Peregrine stared. “Of course she has parents! What can you be thinking of?”

“Evidently of something quite different,” murmured his lordship. “But continue: who are these parents who are known to me by repute?”

“Sir Geoffrey and Lady Fairford,” said Peregrine, watching very anxiously to see how this disclosure would be met. “Sir Geoffrey is a member of Brook’s, I believe. They live in Albemarle Street, and have a place near St. Albans. He is a Member of Parliament.”

“They sound most respectable,” said Worth. “Pour yourself out another glass of wine, and tell me how long you have known this family.”

“Oh, a full month!” Peregrine assured him, getting up and going over to the table.

“That is certainly a period,” said the Earl gravely.

“Oh, yes,” said Peregrine, “you need not be afraid that I have just fallen in love yesterday. I am quite sure of my mind in this. A month is fully long enough for that.”

“Or a day, or an hour,” said the Earl musingly.

“Well, to tell you the truth,” confided Peregrine, reddening, “I was sure the instant I set eyes on Miss Fairford, but I waited, because I knew you would only say something cut—” He broke off in some confusion. “I mean—”

“Something cutting,” supplied the Earl. “You were probably right.”

“Well, I daresay you would not have listened to me,” said Peregrine defensively. “But now you must realize that it is perfectly serious. Only, from the circumstances of my being under age, Sir Geoffrey would have it that nothing could be in a way to be settled until your consent was gained.”

“Very proper,” commented the Earl.

“Sir Geoffrey will have no scruple in agreeing to it if you are not against it,” urged Peregrine. “Lady Fairford, too, is all complaisance. There is no objection there.”

The Earl threw him a somewhat scornful but not unkindly glance. “It would surprise me very much if there were,” he said.

“Well, have I your permission to address Miss Fairford?” demanded Peregrine. “It cannot signify to you in the least, after all!”

The Earl did not immediately reply to this. He sat looking rather enigmatically at his ward for some moments, and then opened his snuff-box, and meditatively took a pinch.

Peregrine fidgeted about the room, and at last burst out with: “Hang it, why should you object?”

“I was not aware that I had objected,” said Worth. “In fact, I have little doubt that if you are of the same mind in six months’ time I shall quite willingly give my consent.”

“Six months!” ejaculated Peregrine, dismayed.

“Were you thinking of marrying Miss Fairford at once?” inquired Worth.

“No, but we—I had hoped at least to be betrothed at once.”

“Certainly. Why not?” said the Earl.

Peregrine brightened. “Well, that is something, but I don’t see that we need wait all that time to be married. Surely if we were betrothed for three months, say—”

“At the end of six months,” said Worth, “we will talk about marriage. I am not in the mood today.”

Peregrine could not be satisfied, but having expected worse, he accepted it with a good grace, and merely asked whether the betrothal might be formally announced.

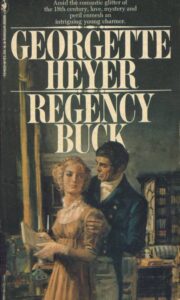

"Regency Buck" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Regency Buck". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Regency Buck" друзьям в соцсетях.