“I desired you to visit me, sir, to explain, if you please, this letter which you wrote me,” said Judith, pulling the offending document out of her reticule.

He took it from her. “Do you know, I never thought that you would cherish my poor notes so carefully?” he said.

Miss Taverner ground her teeth, but made no reply. The Earl, having looked her over with what she could not but feel to be a challenge in his mocking eyes, picked up his eyeglass, and through it perused his own letter. When he had done this he lowered his glass and looked inquiringly at Miss Taverner. “What puzzles you, Clorinda? It seems to me quite lucid.”

“My name is not Clorinda!” snapped Miss Taverner. “I wonder that you should care to call up the recollections it must evoke! If they are not odious to you—”

“How could they be?” said Worth. “You must have forgotten one at least of them if you think that.”

She was obliged to turn away to hide her confusion. “How can you?” she demanded, in a suffocating voice.

“Don’t be alarmed,” said Worth. “I am not going to do it again yet, Clorinda. I told you, you remember, that you were not the only sufferer under your father’s Will.”

Her cousin’s warning flashed into Miss Taverner’s mind. She said coldly: “This way of talking no doubt amuses you, sir, but to me it is excessively repugnant. I did not wish to see you in order to discuss the past. That can only be forgotten. In that letter which you are holding you write that there is no possibility of your consenting to my marriage within the year of your guardianship.”

“Well, what could be plainer than that?” inquired the Earl.

“I am at a loss to understand you, sir. Certain applications have been made to you for—for permission to address me.”

“Three,” nodded his lordship. “The first was Wellesley Poole, but him I expected. The second was Claud Delabey Brown, whom I also expected. The third—now who was the third? Ah yes, it was young Matthews, was it not?”

“It does not signify, sir. What I wish you to explain is how you came to refuse these gentlemen without even the formality of consulting my wishes.”

“Do you want to marry one of them?” inquired the Earl solicitously. “I hope it is not Browne. I understand that his affairs are too pressing to allow him to wait until you are come of age.”

Miss Taverner controlled her tongue with a visible effort. “As it happens, sir, I do not contemplate marriage with any of these gentlemen,” she said. “But you had no means of knowing that when you refused them.”

“To tell you the truth, Miss Taverner, your wishes in the matter do not appear to me to be of much importance. I am glad, of course, that your heart is not broken,” he added kindly.

“My heart would scarcely be broken by your refusal to consent to my marriage, sir. When I wish to be married I shall marry, with or without your consent.”

“And who,” asked the Earl, “is the fortunate man?”

“There is no one,” said Miss Taverner curtly. “But—”

The Earl took out his snuff-box, and opened it. “But my dear Miss Taverner, are you not being a trifle indelicate? You are not proposing, I trust, to command some gentleman to marry you? The impropriety of such an action must strike even so masterful a mind as yours.”

Miss Taverner’s eyes were smouldering dangerously. “What I wish to make plain to you, Lord Worth, is that if any gentleman whom I—if anyone should ask me to marry him whom I—you know very well what I mean!”

He smiled. “Yes, Miss Taverner, I know what you mean. But keep my letter by you, for it tells you just as plainly what I mean.”

“Why?” she shot at him. “What object can you have?”

He took a pinch of snuff, and lightly dusted his fingers before he answered her. Then he said in his cool way: “You are a very wealthy young woman, Miss Taverner.”

“Ah!” said Judith, “I begin to understand.”

“I should be happy if I thought you did,” he replied, “but I feel it to be extremely doubtful. You have a considerable fortune in your own right. More important than this is the fact that under your father’s Will you are heiress to as much of your brother’s property as is unentailed.”

“Well?” said Judith.

“That being so,” said Worth, shutting his snuff-box with a snap and restoring it to his pocket, “there is little likelihood of gaining my consent to your marriage with anyone whom I can at the moment call to mind.”

“Except,” said Miss Taverner through her teeth, “yourself!”

“Except, of course, myself,” he agreed suavely.

“And do you suppose, Lord Worth, that there is any great likelihood of my marrying you?” inquired Judith in a sleek, deceptive voice.

He raised his brows. “Until I ask you to marry me, Miss Taverner, not the least likelihood,” he replied gently.

For fully a minute she could not trust herself to speak. She would have liked to have swept from the room, but the Earl was between her and the door, and she could place no dependence on him moving out of the way. “Have the goodness to leave me, sir. I have no more to say to you.”

He strolled forward till he stood immediately before her. She suspected him of meaning to take her hands, whipped them both behind her, and took a swift step backward. A large cabinet prevented her from retreating further, and the Earl very coolly following, she found herself cornered. He took her chin in his hand, and made her hold up her head, and stood looking down at her with a faintly sardonic smile. “You are handsome, Miss Taverner; you are not unintelligent—except in your dealings with me; you are a termagant. Here is some advice for you: keep your sword sheathed.” She stood rigid and silent, staring doggedly up into his face. “Oh yes, you hate me excessively, I know. But you are my ward, Miss Taverner, and if you are wise you will accept that with a good grace.” He let go her chin, gave her cheek a careless pat. “There, that is better advice than you think. I am a more experienced duellist than you. I have brought you your snuff, and the recipe.”

It was on the tip of her tongue to refuse both, but she bit back the words, aware that they would sound merely childish. “I am obliged to you,” she said in an expressionless voice.

He moved to the door, and held it open. She walked past him into the hall. He nodded to the waiting footman, who at once brought him his hat and gloves. As he took them he said: “I beg you will make my excuses to Mrs. Scattergood. Good night, Miss Taverner.”

“Good night!” said Judith, and turning on her heel, went back into the front drawing-room.

She entered with a somewhat hasty stride and shut the door behind her if not with a slam, at least with a decided snap. Her eyes were stormy; her cheeks looked hot. She flashed a look round the room, and the wrath died out of her face. Mrs. Scattergood was not present; there was only Mr. Taverner, seated by the window, and glancing through a newspaper.

He got up at once, and laid the paper aside. “I am so late. Forgive me, cousin! I was detained longer than I had thought possible—hardly liked to call upon you at this hour, and indeed should have done no more than leave the book with your butler, only that he assured me that you had not retired.”

“Oh, I am glad you came in!” Judith said, holding out her hand to him. “It was kind in you to remember the book. Is this it? Thank you, cousin.”

She picked it up from the table, and began to turn the leaves. Her cousin’s hand laid compellingly over hers made her look up. He was regarding her intently. “What is it, Judith?” he asked in his quiet way.

She gave a little, angry laugh. “Oh, it is nothing—it should be nothing. I am stupid, that is all.”

“No, you are not stupid. Something has occurred to put you out.”

She tried to draw her hand away, but he did not slacken his hold. “Tell me,” he said.

She looked significantly down at his hand. “If you please, cousin.”

“I beg your pardon.” He stepped back with a slight bow.

She put the book aside, and moved towards a. three-backed settee of lacquered wood and cane, and sat down. “You need not. I know you only wish to be kind.” She smiled up at him. “I am not offended with you, for all I may look to be in one of my sad passions.”

He followed her to the settee, and at a sign from her seated himself beside her. “It is Worth?” he asked directly.

“Oh, yes, it is, as usual, my noble guardian,” she replied, with a shrug of her shoulders.

“Mrs. Scattergood informed me that he was with you. What has he been doing or must I not ask?”

“I brought it upon myself,” said Judith, incurably honest. “But he behaves in such a way—oh, cousin, if my father had but known! We are in Lord Worth’s hands. Nothing could be worse! I thought at first that he was amusing himself at my expense. Now I am afraid—I suspect him of a set purpose, and though it cannot succeed it can make this year uncomfortable for me.”

“A set purpose,” he repeated. “I may guess it, I suppose.”

“I think so. It was you who put me a little on my guard.”

He nodded; he was slightly frowning. “You are very wealthy,” he said. “And he is expensive. I do not know what his fortune is; I imagined it had been considerable, but he is a gamester, and a friend of the Regent. He is in the front of fashion; his clothes are made by the first tailors; his stables are second to none; he belongs to I dare not say how many clubs—White’s, Watier’s, the Alfred (or, as I have heard it called, the Half-Read), the Je ne sais quoi, the Jockey Club, the Four Horse, the Bensington—perhaps more.”

“In a word, cousin, he is a dandy,” Judith said.

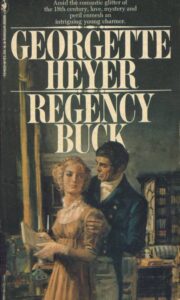

"Regency Buck" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Regency Buck". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Regency Buck" друзьям в соцсетях.