Within a week the rich Miss Taverner’s phaeton was one of the sights of town, and several aspiring ladies had attempted something in the same style. But since no one, with the exception of Lady Lade, who was so vulgar and low-born (having been before her marriage to Sir John the mistress of a highwayman known as Sixteen-String Jack) that she could not be thought to count, could drive one horse, let alone a pair, with anything approaching Miss Taverner’s skill, these attempts were soon abandoned. To be struggling with a refractory horse, or jogging soberly along behind a sluggish one, while Miss Taverner dashed by in her high phaeton could not add to any lady’s consequence. Miss Taverner was allowed to drive her pair unrivalled.

She did not always drive, however. Sometimes she rode, generally with her brother, and occasionally with Lord Anglesey’s lovely daughters, and very often with her cousin, Mr. Bernard Taverner. She rode a very spirited black horse, and it was not long before Miss Taverner’s black was as well known as Lord Morton’s long-tailed grey. She had learned the trick of acquiring idiosyncrasies.

In a month the Taverners were so safely launched into Society that even Mrs. Scattergood admitted that there did not seem any longer to be anything to fear. Peregrine had not only been made a member of White’s, but had contrived to get himself elected to Watier’s as well, its perpetual President, Mr. Brummell, having been induced to choose a white instead of a black ball on the positive assurance of Lord Sefton that Peregrine would bring into the club not the faintest aroma either of the stables or of bad blacking—an aroma which, in Mr. Brummell’s experience, far too often clung to country squires.

He went as Mr. Fitzjohn’s guest to a meeting of the Sublime Society of Beefsteaks at the Lyceum, and had the felicity of seeing there that amazing figure, the Duke of Norfolk, who rolled in looking for all the world like a gross publican, and presided over the dinner in dirty linen and an old blue coat; ate more beefsteaks than anyone else; was very genial and good humoured; and fell sound asleep long before the end of the meeting.

He took sparring lessons at Jackson’s Saloon; shot at Manton’s Galleries; fenced at Angelo’s; drank Blue Ruin in Cribb’s Parlour; drove to races in his own tilbury, and generally behaved very much as any other young gentleman of fortune did who fancied himself as a fashionable buck. His conversation became interlarded with cant expressions; he lost a great deal of money playing at macao, or laying bets with his cronies; drank rather too much; and began to cause his sister a good deal of alarm. When she expostulated with him he merely laughed, assured her he might be trusted to keep the line, went off to join a party of sporting gentlemen, and returned in the small hours considerably intoxicated, or—as he himself phrased it—a trifle above par.

Judith turned to her cousin for advice. With the Admiral she could never be upon intimate terms, but Bernard Taverner had very soon become a close friend.

He listened to her gravely; he agreed with her that Peregrine was living at too furious a rate, but said gently: “You know I would do anything in my power for you. I have seen all you describe, and been sorry for it, and wondered that Lord Worth should not intervene.”

She turned her eyes upon him. “Could not you?” she asked.

He smiled. “I have no right, cousin. Do you think Perry would attend to me? I am sure he would not. He would write me down a dull fellow, and be done with me. It is—” he hesitated. “May I speak plainly?”

“I wish you would.”

“Then I will say that I think it is for Lord Worth to exert his authority. He alone has the right.”

“It was Lord Worth who put Perry’s name up for Watier’s,” said Judith bitterly. “I was glad at first, but I did not know that it was all gaming there. It was he who took him to that horrid tavern they call Cribb’s Parlour, where he meets all the prizefighters he is for ever talking about.”

Mr. Taverner was silent for a moment. He said at length: “I did not know. Yet he could hardly be blamed: it is his own world, and the one Perry was all eagerness to enter. Lord Worth is himself a gamester, a very notable Corinthian. He is of the Carlton House set. It may be that he is not concerning himself very closely with Perry’s doings. Speak to him, Judith: he must attend to you.”

“Why do you say that?” she asked, frowning.

“Pardon me, my dear cousin, it has seemed to me sometimes that his lordship betrays a certain partiality—I will say no more.”

“Oh no!” she said, with strong revulsion. “You are mistaken. Such a notion is unthinkable.”

He made a movement as though he would have taken her hand, but controlled it, and said with an earnest look: “I am glad.”

“You have something against him?” she said quickly,

“Nothing. If I was afraid—if I disliked the thought that there might be some partiality, you must forgive me. I could not help myself. But I have said too much. Speak to Lord Worth of Perry. Surely he cannot want him to be growing wild!”

She was a good deal stirred by this speech, and by the look that went with it. She was not displeased: she liked him too well; but she wished him to say no more. A declaration seemed to be imminent; she was thankful that he did not make it. She did not know her own heart.

His advice was too sensible to be lightly ignored. She thought about it, realized the justice of what he had said, and went to call on Worth, driving herself in her phaeton. To request his coming to Brook Street would mean the presence of Mrs. Scattergood; she supposed there could be no impropriety in a ward’s visiting her guardian.

She was ushered into the saloon, but after a few minutes the footman came back, and desired her to follow him. She was conducted up one pair of stairs to his lordship’s private room, and announced.

The Earl was standing at a table by the window, dipping a sort of iron skewer into what looked to be a wine-bottle. On the table were several sheets of parchment, a sieve, two glass phials, and a pestle and mortar of turned boxwood.

Miss Taverner stared in considerable surprise, being quite unable to imagine what the Earl could be doing. The room was lined with shelves that bore any number of highly glazed jars and lead canisters. They were all labelled, with such queer-sounding names as Scholten, Curacao, Masulipatam, Bureau Demi-gros, Bolongaro, Old Paris. She turned her eyes inquiringly towards his lordship, still absorbed in his bottle and skewer.

“You must forgive me for receiving you here, Miss Taverner, but I am extremely occupied,” he said. “It would be fatal for me to leave the mixture in its present state, or I would have come to you. Have you left Maria Scattergood downstairs, may I ask?”

“She is not with me. I came alone, sir.”

There seemed to be a fine powder in the wine-bottle. The Earl had extracted a little with the aid of the skewer and dropped it into the mortar, and had begun to mix it with what was already there, but he paused at Miss Taverner’s words, and looked across at her in a way hard to read. Then his gaze returned to the mortar, and he went on with his work. “Indeed? You honour me. Will you not sit down?”

She coloured faintly, but drew forward a chair. “Perhaps you may think it odd in me, sir, but the truth is I have something to say to you I do not care to say before Mrs. Scattergood.”

“I am entirely at your service, Miss Taverner.”

She pulled off her gloves and began smoothing them. “It is with considerable reluctance that I have come, Lord Worth. But my cousin, Mr. Taverner, advised me—and I cannot but feel that he was right. You are after all our guardian.”

“Proceed, my ward. Has Wellesley Poole made you an offer of marriage?”

“Good heavens, no!” said Judith.

“He will,” said his lordship coolly.

“I have not come about my own affairs, sir. I desire to talk to you of Peregrine.”

“Life is full of disappointments,” commented Worth. “Which spunging house is he in?”

“He is not in any,” said Judith stiffly. “Though I have little doubt that that is where he will end if something is not done to prevent him.”

“More than likely,” agreed Worth. “It won’t hurt him.” He picked up one of the phials from the table and delicately poured a few drops of what it contained on to his mixture.

Judith rose. “I see, sir, that I waste my time. You are not interested.”

“Not particularly,” admitted the Earl, setting the bottle down again. “The intelligence you have so far imparted has not been of a very interesting nature, has it?”

“It does not interest you, Lord Worth, that your ward is got into a wild set of company who cannot do him any good?”

“No, not at all; I expected it,” said Worth. He looked up with a slight smile. “What has he been doing to alarm his careful sister?”

“I think you know very well, sir. He is for ever at gaming clubs, and, I am afraid—I am nearly sure—worse than that. He has spoken of a house off St. James’s Street.”

“In Pickering Place?” he inquired.

“I believe so,” she said in a troubled voice.

“Number Five,” he nodded. “I know it: a hell. Who introduced him to it?”

“I am not perfectly sure, but I think it was Mr. Farnaby.”

He was shaking his mixture over one of the sheets of parchment. “Mr. Farnaby?” he repeated.

“You know him, sir?”

His occupation seemed to demand all his attention, but after a moment he said, ignoring her question: “I gather, Miss Taverner, that you consider it is for me to—er—guide Peregrine’s footsteps on to more sober paths?”

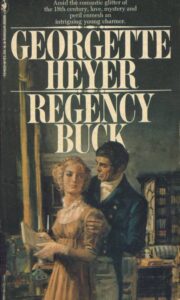

"Regency Buck" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Regency Buck". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Regency Buck" друзьям в соцсетях.