But he had succeeded only in hurting her deeply, in making it seem as if he wanted to destroy her sense of self. She had seen his actions as an unforgivable example of tyranny, spying on her in her most private moments.- She hated him now worse than ever, and he could hardly blame her. He was consumed by an agony of remorse. He had had no right to listen to her all those times, uninvited.

Holding her in his arms the day before had been a terrible agony, because he knew as he did so that it would be the last time he would ever touch her. He had known that as soon as she recovered from her fit of sobbing he would tell her that he would stay away from her, never force his presence on her again. And even then he had not been able to resist one final act of self-indulgence. He had kissed her.

And fare-thee-well, my only Luve,

And fare-thee-well, a while!

The words of that song would haunt him forever, he felt. The next line would never apply to him, though: "And I will come again, my Luve." He would never be able to come to her again now. Once she was gone, he would probably never see her again, except for a chance glimpse at some ton event when she was in town, perhaps. And she might as well be gone already. He had pledged not to see her while she remained in his house, except on Friday evening, if she still planned to attend his concert.

Raymore thought about Sir Bernard Crawleigh. He hated to think of Rosalind belonging to him. The man was pleasant enough, he supposed, and he would certainly never ill-treat her. But there was no depth to the man's character. He still kept a mistress at an establishment that he owned. Raymore had checked quite carefully into the matter within the last week. And Crawleigh had made a lengthy call there since his return to London. The fact did not call for any great alarm. Crawleigh might be a perfectly decent husband despite the existence of a mistress. He would merely be doing what a large number of other husbands did. But it was not good enough for Rosalind, Raymore decided. She was very special: intelligent, talented, very cultured. She needed a man who could match her passion for the beauties of life. And Crawleigh was definitely not that man.

Had she chosen him freely? Had he himself pushed her into the betrothal by making such an infernal to-do over the episode in Letty's summerhouse? Had his treatment of her in general forced her to consider marriage to Crawleigh a welcome escape from his guardianship? Or did she love the man? It was impossible to know the answer.

But Raymore made a decision. Before he left the house, he wrote a letter, which he left with the housekeeper to deliver to Rosalind the following morning. He would have liked to speak with her himself, but he could not for two reasons. He had promised that she would not have to see him before Friday night. Also, he knew from experience that any meeting between the two of them was bound to flare into an angry quarrel. He did not wish to quarrel with her ever again. He wanted to love her.

Both letters were received the following morning. Rosalind was sitting at the breakfast table alone when she broke the seal of hers. She could not understand why her guardian would be writing to her unless it was in reply to her own note. Perhaps he had changed his mind and did not wish her, after all, to play at his concert. She read:

My dear Rosalind,

In reflecting on our conversation of yesterday afternoon, it has occurred to me that you might have engaged yourself to marry Sir Bernard Crawleigh only as a means of escaping my control over your affairs. I would not wish to drive you into an unwelcome marriage.

If your heart is engaged, I sincerely wish you joy of your union. But if not, I urge you to put an end to the betrothal. I shall send you home to Raymore Manor next week and allow you to live there for the rest of your life as if it belonged to you. I shall release to you control of your fortune and engage never to enter the property without an express invitation from you. You can be free, Rosalind. All this I am willing to put in legal form if you so choose.

Believe me when I say that I wish only what is best for you, and that I remain now and always,

Your servant,

Edward Marsh, Earl of Raymore.

Damn him, she thought, crumpling the paper and holding it rightly in her hand. He was determined, it seemed, to keep her mind and her life in turmoil. She had disliked him from the start, but at least then he could always be relied upon to behave consistently. She had labeled him as a cold man, totally devoid of all the finer feelings in life. It would have been more comfortable for her peace of mind if he had not recently begun behaving as if he had a heart. Even two days ago it had been hard to continue hating him, but at least then she could convince herself that his gentleness had an ulterior motive. But what could be his motive this time? He must already have had her letter telling him that she would play at his concert. She could not explain his letter in any other way than by seeing it as a sincere attempt to give her some freedom of choice about her future. Oh, damn him!

And what about the choice he had given her? Why did everyone seem intent upon putting doubts in her mind just at a time when she was feeling less than certain about her own feelings? She wanted to marry Bernard, of course she did. He was handsome, kindly, good-humored. He was the only man who had ever shown a real interest in her, if one discounted Sir Rowland Axby and the strange advances of her guardian. She could be happy with him. Only a few months before, she had resigned herself to a life of spinster-hood, believing that no man could tolerate her disability and her dark, unfashionable looks.

But first Lady Elise and now Raymore were attempting to make her take a closer look at her feelings. She did not wish to do so. She was terrified of doing so, in fact. She wanted to be safe. Lady Elise had even made the quite absurd suggestion that she loved the Earl of Raymore. And she had always considered her new friend to be a woman of good judgment. She was not going to stop to think about him. She was already too disturbed by the uncharacteristic nature of his behavior in the past two days. She would not think anymore.

Rosalind spread the letter on the table before her and folded it carefully into its original creases. She would not think about him or about her betrothal until Saturday. She had only two days to prepare herself for the concert. It was imperative that she be calm so that all her concentration could be given to her music. She rose from the table, her breakfast untouched, and went to the morning room to write a letter to Sir Bernard, canceling a dinner engagement with him that evening and explaining that she needed to be alone until Friday evening to prepare her mind as well as to practice her music. Then she went to the music room to make the best use of her time until the Austrian arrived.

For his part, Raymore was handed Rosalind's note when he returned very early to his own house. He had spent the night playing cards, or most of the night, anyway. Late in the evening he had kept an appointment to escort the new actress from Hamlet to dinner and then to her home. He completely mystified and enraged her when, after a half-hearted conversation of ten minutes' duration, he picked up his cloak and took his leave of her without having so much as touched her Her anger was somewhat mollified when she saw the number of bank notes he had deposited on the table where his hat had been, but she still made straight for a mirror after he had left and gazed at her own image, wondering what defect had turned away such a desirable protector.

He was done with such unsatisfactory liaisons, Raymore decided during the course of the night. Occupying a woman's body could bring him no further delight unless the woman herself was the object of his love. When Rosalind was gone, he would make an honest effort to find himself another woman whom he could love. He doubted that it was possible, but he would take the risk. He had been absent from life too long.

Rosalind's note delighted him. She had given him a last chance to show her that he esteemed her for herself. He must be very careful of the way he introduced her and of what he said to her afterward, if he had a chance to speak to her at all. Most of all, he wanted her to see that his assessment of her talent was correct. If she received the acclaim that he expected, she would have restored to her the confidence that her lameness and the loss of her parents had deprived her of at a very early age.

Tired as he was, Raymore took the stairs to his room two at a time and rang for a hot bath.

The next two days were intense ones for Rosalind, who practiced morning and night and shut herself into her room during the afternoons. Nothing was to be allowed to disturb her concentration. At first she found that her playing was full of mistakes and that the music itself was lifeless. She had to make a determined effort to control her nervousness. There was really no need to be afraid. The people who were coming on Friday night were coming, not in the hope that she would fumble, nor in order to criticize. They were coming to be entertained. And she was not even the star attraction. She was capable of performing well. He had said so and she must trust his judgment. Strangely, Rosalind found in the end that the best calming influence on her was to see his face before her, the rather austere aquiline features, the intense blue eyes, the blond hair. It was a face that could be trusted, as far as her music went, anyway. She played for him. She would play for him on Friday.

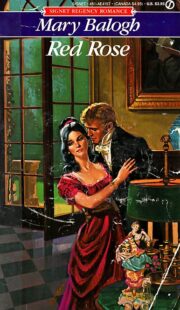

"Red Rose" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Red Rose". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Red Rose" друзьям в соцсетях.