I stare up at her. My urge to vomit has passed. I’m seized by a new urge… to hug her.

I know better than to act on this urge, however. Instead, I hug myself, and say in a soft voice, “Thanks, Tiffany. I… it’s been kind of… weird.”

“I can imagine,” Tiffany says, sauntering the rest of the way across the room to her chair and collapsing into it. “I mean, for you. You’re not used to being a bad girl. But the thing is”—she reaches into her enormous bag and pulls out a chocolate croissant, then gestures for me to make her a cappuccino, which I do—“you’re not really even being that bad. You know? I mean, it’s not like you and Luke are married. You’re engaged. And, like, barely. You haven’t even set a date. On the Bad Girl Scale, ten being really bad, and zero being barely bad, you’re like a one.”

I hand her the cappuccino I’ve whipped up, having already turned on the machine when I got in. “What are you?”

“Me?” Tiffany bites into her croissant and chews thoughtfully. “Well, let’s see. Raoul’s married, but his wife left him for her personal trainer. The only reason they aren’t divorced is because he doesn’t have his green card yet. As soon as he gets it—which should be any day now—he’s going to divorce her and marry me. But we are living together. So, on the Bad Girl Scale, I’m like a four.”

I’ve never heard of the Bad Girl Scale—never having done anything before to put me on it. I’m genuinely interested.

“What’s Ava?” I want to know.

“Ava? Oh, let’s see. She’s sleeping with this DJ Tippycat guy, and he’s married. But, according to the tabloids, his wife came after him in an Outback Steakhouse parking lot with a chain saw, so he’s got a restraining order out on her. That only puts her at about a five on the Bad Girl Scale.”

“That’s higher than you,” I say, impressed.

“True,” Tiffany says. “Tip’s got a rap sheet. He tried to take an ounce of marijuana on a plane once. It was in one of his kid’s stuffed animals. But still. Oh my God. I have to remember to tell Ava about you and Chaz. She’s gonna be stoked. She had a fifty riding on it too. Little Joey’s got a hundred on it!”

“Please,” I say, raising a hand. Ava’s a bit of a sensitive subject, since she still hasn’t spoken to me since that morning we woke up to find the paparazzi swarming outside the shop. “Can we just keep it on the D.L. for now? There are people who don’t know that I’m trying to figure out how—or if—I’m going to tell. Like Luke.”

Tiffany blinks at me. “What do you mean, if? Of course you’re gonna tell Luke.”

I look down at the ring I’m still wearing on my left hand and don’t say anything.

“You are going to break up with Luke, right, Lizzie?” Tiffany demands. “Right, Lizzie? Because, oh my God, if you don’t, do you know what number you go to on the Bad Girl Scale? Like, directly to ten. You cannot string along both those guys at the same time. Who do you think you are, anyway? Anne Heche?”

“I know,” I say with a groan. “But it’s just going to hurt Luke so much. Not the part about me, but the part about Chaz. I mean, he’s his best friend… ”

“That’s Chaz’s problem,” Tiffany says. “Not yours. Come on, Lizzie. You can’t have them both. Well, I mean, I could. But you can’t. You wouldn’t be able to handle it. Just look at you. You’re falling apart as it is, and one of them isn’t even on the same continent, and there’s no chance of you getting caught. You’re going to have to decide. And, yes, one of them is going to get hurt. But you should have thought of that before you decided to become a Bad Girl.”

“I didn’t decide to become a Bad Girl,” I insist. “It just happened. I couldn’t help it.”

Tiffany shakes her head. “That’s what they all say.”

At that moment the bells over the front door tinkle, and Monsieur Henri comes in, followed by his wife, looking tight-faced, and another woman I’ve never seen before. The woman is dressed in a summer-weight business jacket and skirt and is carrying a briefcase. She looks a little too young to be a mother of the bride, but a little too old to be the kind of bride who wears the type of gowns in which we generally specialize. Not to be ageist or anything. But it’s true.

“Ah, Elizabeth,” Monsieur Henri says when he sees me. “You’ve returned, I see. We were very sorry to hear of your loss.”

“Um,” I say. I haven’t seen Monsieur Henri since his first—and last—venture to the city after his heart surgery. According to his wife, with whom I’ve spoken on the phone several times since then, he’s been back at their home in New Jersey, brushing up on his pétanque skills and watching Judge Judy. “Thank you. I’m sorry I was away for so long.”

I was actually gone for four days, only two of which were actual workdays. But I can’t think of any other reason why Monsieur Henri should be back so suddenly, and with what appear to be reinforcements.

“Not to worry, not to worry,” Monsieur Henri says, waving my concerns off as if they were nothing. “Now, Miss Lowenstein. This is the shop, as you can see. Let me take you into the back room.”

“Thank you,” Miss Lowenstein says, giving me the briefest of smiles as she passes by, following closely behind Monsieur Henri.

I turn my bewildered gaze on Madame Henri, who can barely look me in the eye. “Oh, Elizabeth,” she says to the carpet. “I hardly know what to say.”

“Oh, yeah,” Tiffany says, breaking off while taking a slurp of her cappuccino. “I totally forgot to tell you… ”

F or many years it’s been assumed that the wedding veil, which was traditionally worn over the face, was used to disguise the bride, and thus protect her from evil spirits. But more recent historians argue that perhaps the veil served a more practical purpose… the veil may actually have been to keep her betrothed, in case of an arranged marriage, from seeing the face of his intended until after he was already committed. A less than charitable interpretation, but have you seen some of those twelfth-century portraits?

Tip to Avoid a Wedding Day Disaster

Make sure the color of your veil matches that of your dress! Not all whites are the same. Never choose an ivory veil to go with a cream-colored dress. You might think the difference is slight, but believe me, it will show up in the photos, and you’ll notice, and slowly, over the years, looking at the photos will drive you insane. Make sure you match the color of your dress to your veil. These are two items you won’t want to mix and match.

LIZZIE NICHOLS DESIGNS™

• Chapter 19 •

Marriage—a book of which the first chapter is written in poetry and the remaining chapters written in prose.

Beverley Nichols (1898–1983), English writer and playwright

“I should have told you,” Madame Henri says miserably as she dumps another sugar packet into her latte. We’re sitting at a table in the window booth at the corner Starbucks, and she keeps glancing nervously toward the doors of the Goldmark Realty Offices, through which her husband has disappeared with Miss Lowenstein, Goldmark’s self-proclaimed top sales agent. “But it was all decided so suddenly, and you’d already had the bad news about your grandmother… I just didn’t have the heart to pile on this bad news as well.”

“I understand,” I say.

I don’t, actually. I really don’t see how, after everything I’ve done for them—all my hard work these past six months—they can do this to me. I mean, I can—it’s their business, after all, and they have the right to sell it if they want to. But it seems awfully cold. On the Bad Girl Scale, I’d give what they’re doing about a five hundred.

“So… he really just wants out?”

“He wants to go back to France,” Madame Henri says glumly. “It’s so strange. All these years, before the heart attack, I was begging him to take more time off, to spend more time with me at our house in Provence, and he wouldn’t hear of it. For him, it was always work, work, work. Then he has the heart attack, and suddenly… he doesn’t want to work anymore. At. All. All he wants to do is play pétanque. That’s all I hear about. Pétanque this and pétanque that. He wants to retire to our house in Avignon and just play pétanque until he dies. He’s already contacted his old friends there—his schoolmates—and formed a team. They have a league. A pétanque league. It’s insane. I suppose I should be glad he’s found something that interests him. After the operation, I thought nothing would, ever again. But this… it’s obsessive.”

I look down at the Diet Coke I’ve bought but haven’t even opened yet. I can hardly believe this is happening. How could my day, which had started out so incredibly well, be going downhill so fast?

“But… what about your boys?” I ask. “I mean, doesn’t he want them to come with you?”

I can’t imagine Provence would hold any appeal whatsoever for the two club-hopping Henri boys.

“Oh, no, of course not,” Madame Henri says. “No, and they don’t want to come with us. They have to stay and finish school. But that’s why we need to sell the building. We’ll need something to pay for that. New York University is so expensive.” She sighs. Her eyeliner, usually so carefully and expertly put on, is smudged, a clear sign of the stress she’s under. “And then we’ll need something to live on. If he’s doing nothing but playing pétanque all day… I suppose I could look for work, but there isn’t much a middle-aged woman who used to manage a bridal gown refurbishment shop can do in the south of France.” She sighs again, and I can see the pain the admission has caused her.

“Of course,” I say. The urge to vomit that I’d felt while speaking to Tiffany earlier returns. “And you don’t think you can get by just from the sale of your house in New Jersey?”

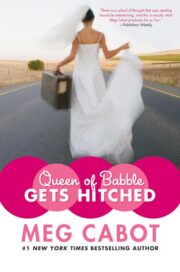

"Queen of Babble Gets Hitched" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Queen of Babble Gets Hitched". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Queen of Babble Gets Hitched" друзьям в соцсетях.