The meetings of Huguenots and Catholics continued and some agreement was reached. She had Navarre’s assurance that he wished to keep his wife with him; and Margot had said that she would stay in her husband’s kingdom. So now Catherine was ready to return to Paris.

Navarre was satisfied by the agreement he had made with the King of France through the Queen Mother. Huguenots and Catholics were now more or less of equal standing in France; nineteen towns had been made over to the Huguenots. Catherine was leaving, and that delighted him, for he neither liked nor trusted his mother-in-law; she was taking Dayelle with her, and Dayelle had been a charming mistress, but he had for some weeks had his eye on a frail and delicate creature—a Mademoiselle de Rebours, who seemed different from any woman he had loved before, as he usually chose them for healthy looks which matched his own. No, he had few regrets when he contemplated the departure of the Queen Mother.

As for Margot she was so deeply absorbed in her love affair with the handsome Turenne that she had forgotten her longing for Paris. And so, unregretted, Catherine began her journey northwards.

But her troubles were not over. There had been an attempted rising against the crown in Saluces, a town of some importance because of its position on the borders of France and Italy. A certain Bellegarde, who was the Governor of the dominion of Saluces, had descended on the capital town and fortified it against the French.

Catherine was travelling through Dauphine when she heard this news, and she summoned Bellegarde to her there; but he ignored the summons; she then ordered the Duke of Savoy to bring the man to her; and after an irritating delay of weeks, during which her desire to see the King made her both uneasy and depressed, the man was brought to her.

With the Cardinal of Bourbon at her side, she received Belle-garde and the Duke of Savoy.

She talked sadly to them of the virtues of the King, of all he had done for his subjects; she spoke of the shock it was to her to discover that there were those who did not appreciate his goodness. She wept a little. She brought out her favourite fiction: ‘Who am I but a weak woman? What can I say to you? How can I deal with traitors?’

Bellegarde was so overcome by her tears and her eloquence that he wept with her; but when she asked him what he intended to do about the dominion of Saluces, he talked at length of the religious differences between the people of that town and the court of France, and he stressed his opinion that the will of the people must be taken into account. He could not be held responsible for what had happened, he told Catherine; the people had simply chosen him as their mouthpiece because he was their Governor.

‘Monsieur,’ said Catherine, no longer the weak widow, have come to settle this matter and nothing more. I shall not leave this town—nor shall you—until you have sworn an oath of allegiance to the King. If you will not do so . . .’ She shrugged her shoulders and gave him the full force of one of those quiet smiles which had never failed to terrify all those on whom they were bestowed.

The outcome of his interviews with the Queen Mother was that Bellegarde, in the presence of the council, vowed his allegiance to the King. But Catherine was not satisfied with this man’s conduct. She kept him surrounded by spies, and nothing he said or did was allowed to go unnoticed.

‘I do not trust a man who has betrayed his King,’ she said to the Cardinal of Bourbon. ‘It is never wise to do so.’

She certainly did not trust Bellegarde. He died quite suddenly one night. There had seemed nothing wrong with him on the previous day and he had eaten a hearty supper and drunk his share of wine.

Catherine was now free to go back to her son.

She shed real tears of joy when once more she held his scented body in her arms.

It did not take Catherine long to realize that while she had been away time had not stood still at the court of France; and she began to wonder whether she could not have been better employed by staying at court than effecting a peace between Huguenots and Catholics and patching up a marriage, the parties of which were two such feckless and immoral people that they had no more hope of achieving happiness together than had the Huguenots and Catholics.

She was greatly disturbed by the activities of one man about whom she feared she had not thought sufficiently during the months she had been absent. It was never wise to forget the existence of the Duke of Guise.

The Catholic League, she discovered, had grown enormously since she had left Paris. It was spreading its roots all over the country, and offshoots were springing up in most towns. It was supported by Spain and Rome. What was the object of this League? Not quite what it professed, she was sure. It was reputed to be endeavouring to bring comfort to the multitude, but Catherine suspected that its real object was to bring power to one man.

She had found that the extravagances of the King were as great as ever. Joyeuse and Epernon were now his chief darlings. Joyeuse was but a simpering fool; but she was not sure of Epernon. Henry had made gifts to his friends of hundreds of his abbeys, and these places were now mainly in the hands of people who should have had no connexion with them at all. The Battus paraded the streets with their fantastic processions; and the King’s banquets had become more preposterously extravagant.

Catherine was terrified, too, of what her younger son, Anjou, would do next; and when Queen Elizabeth declared to Simiers, who was now in England trying to persuade the Queen to a French marriage, that she would not marry a man whom she had not seen, Catherine felt it was a Heaven-sent opportunity to rid France of the mischievous youth; and, if Elizabeth would be so benevolent as to keep him, she should have the sincere gratitude of his mother.

Anjou, looking for fresh adventures, was not averse to making the journey, and so, one day in June, he crossed the Channel and landed in England.

Catherine, with the aid of her spies, followed that most farcical of all courtships. She knew that Elizabeth was as shrewd as she was herself, but that the Englishwoman was possesed of many feminine qualities with which Catherine was not burdened. Catherine laughed to contemplate that other Queen, whose vanity she believed was her most powerful characteristic. She knew of the coquetting with Leicester, who, in despair of ever marrying the Queen and becoming King of England, had recently married the Countess of Essex in secret. Simiers and his spies had, on Catherine’s orders, brought this about by assuring Leicester that the French match was further advanced than he knew, and that he had no prospect of marrying the Queen, since she had decided on the Duke of Anjou.

As for her son’s method of courting the woman who was forty-six while he was only twenty-five, she left that to him; he was, after all, very experienced in the ways of making love.

So Anjou went in disguise to Greenwich Palace, asked permission to see the Queen, and when it was granted—for she was well aware who her visitor was—threw himself at her feet murmuring that his admiration rendered him speechless.

Elizabeth found this method of approach romantic and enchanting, although it set her countrymen jeering at French habits and customs. She confided to her ladies—and this was brought back to Catherine—that he was far less ugly than she had been led to believe. His nose was big, admitted the Queen of England, but all the Valois had big noses, and she had not expected his to differ very much from those belonging to other members of his family; if his skin was pitted by the smallpox, she was prepared for that; he was small, it was true, but that merely made her feel tender towards him. She liked his fancy manners; he was bold, but she liked his boldness; and he could dance more daintily than any English courtier.

Catherine knew that the red-headed Queen was making secret fun of her suitor, just as her subjects did. In the streets young gallants and even apprentices would affect mincing manners as they walked, deliberately provoking the onlookers to laughter; these young men had taken to exaggerated fashions, copied, they said, from ‘Mounseer’—as they called Anjou—and his pretty entourage. Catherine knew that once Anjou realized that he was being made fun of, he would be furious; but apparently the dry-humoured English had managed to keep this from him.

The Queen petted him as she might have petted a monkey; she made him appear with her in public; she called him her ‘little frog’.

She knew, of course, that her actions were being watched. She was coquettish and vain enough to wish to be courted by the quaint ‘Mounseer’, but at the same time she had an eye for the advantages and the disadvantages of such a match. A Protestant Queen of forty-six to marry a Catholic Prince of twenty-five! It was not the most satisfactory match she could have made, but as long as her ministers dissuaded her, she was ready to view it with favour, simply because she wished to keep the young man gallantly dancing attendance on her as long as possible.

Catherine had seen a copy of the letter the great Sir Philip Sydney had written to the Queen concerning this marriage. It was daring, and as she read it, Catherine wished she could have asked Sir Philip to dine with her. He would not long have survived that meal.

Most beloved, feared, most sweet and gracious Sovereign. How the hearts of your people will be galled—if not alienated—when they shall see you take a husband, a Frenchman and a Papist, in whom the very common people know this, that he is the son of that Jezebel of our age—that his brother made oblation of his own sister’s marriage, the easier to make massacre of our brethren in religion. As long as he is Monsieur in might and a Papist in profession, he neither can nor will greatly shield you; and if he grow to be a King, his defences will be like Ajax’ sword, which rather weighed down than defended those that bare it.’

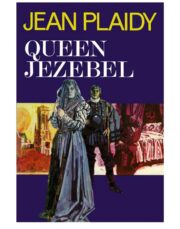

"Queen Jezebel" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Queen Jezebel". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Queen Jezebel" друзьям в соцсетях.