The nuts had been placed on the table, and my uncle Montague was well into his fourth cup of wine and loudly declaiming on politics when Romeo at last stumbled into the hall. I say stumbled as an accurate description; he tripped on a rug, skidded, and grabbed onto a servant to stay upright. The servant noisily dropped a tray containing the sticky remains of roast pork, and Romeo immediately pushed away, heading with speed but not precision toward the table. As always, he left damage in his wake.

“You’re not Veronica,” he said to me as he poured himself into his usual chair. “Ronnie usually sits there, and she’s far prettier company.”

“She’s out of favor with Grandmother,” I said.

“For what?”

“Ignoring her summons.”

He laughed with wine-fueled good humor. “Good for Ronnie. If we didn’t bow and scrape so much to the old witch, life would be infinitely sweeter.” Romeo balanced his chair up on two wavering legs, and spotted Veronica sitting at the far end of the table with our youngest and most disfavored country cousins. She looked mutinous and flushed, and Romeo gave her a drunken little wave, which she ignored with a lift of her chin.

I kicked the side of his chair, which made it wobble even more unsteadily; Romeo thumped it back down to four legs with more alarm than grace. “Attend me, fool. It’s not just Ronnie who’s in disfavor. Grandmother’s not well pleased with you, either.”

“She’s never well pleased with any of us, save perhaps for you, O perfect one,” he said, and waved a servant over. The servant in question had a strained, long-suffering look as he bent to listen. “Where lurks dinner?”

“It has been served, master,” the servant said. I didn’t know this one by name; he was new, I supposed, though he seemed flawlessly well trained. “Shall I bring you soup?”

“Soup and bread. And wine—”

“Water,” I interrupted. “Bring him water, for God’s sake and his own.”

“A traitor at my side,” my cousin said. The servant left, looking relieved.

“Where were you?” I asked Romeo.

He let his head drop against the high back of the chair. We looked similar, but I was taller, broader, and not as handsome. My nose had once been just as fine and straight, but a street brawl with the Capulets had done for that decisively. At least one maid had claimed it granted me character, as did the faint scar that cut through my eyebrow, so there was some benefit to my adventures. And, of course, my eyes. My eyes always betrayed my half-foreign ancestry.

“Hmmm. Where was I?” Romeo echoed dreamily as his eyelids drooped. “Ah, coz, I was in contemplation of peerless beauty, but it is a beauty that saddens. She is too fair, too wise, wisely too fair, since she refuses to hear my suit.”

He was very drunk, and coming dangerously near declaiming his wretched poetry. “Who inspires you to such heights of nonsense?”

“I shall not cheapen her name in such company, but in sadness, cousin, I do love a woman.”

“We’ve all loved women, and almost always sadly.” Well, I reflected, almost all of us had done so. But that was another subject that needed no expression here. “We’ve survived the harrowing.”

Romeo, even drunk, was sensible enough to know that uttering a Capulet’s name at a Montague dinner table wasn’t sane. He left it to me to read between his lines. “Not I,” he said. “She cannot return my love; she’s vowed elsewhere. I live dead, Benvolio. I am shattered and ruined with love.”

The servant returned with a bowl of hot soup, which he deposited in front of Romeo, along with a plate of fresh bread. The soup steamed gently in the cool air, and I smelled pork and onion in the mix, along with sage. Romeo picked up the bread and sopped a piece in the broth.

“I see death hasn’t dimmed your appetite,” I observed. “Do you think to change the girl’s mind?”

“I must, or sicken and wither.” He said it with unlikely confidence, and took a bite of the bread. “Already my words are in her hands tonight. They’ll add to the chorus proclaiming my faithfulness. She will favor me soon.”

“Chorus . . . How many of these missives have you sent to her?”

“Six. No, seven.”

I stared at him as he spooned up the soup. I was hard-pressed to bring myself to ask the question, but I knew I must. “And did you . . . sign them?”

“Of course,” said the idiot, and missed his mouth with the spoon, spilling hot liquid all over his chin. “Ouch.” He wiped at it with the back of his hand, frowned at the bowl, and raised it to his mouth to take a blistering gulp. “I could not let her ascribe them to some other suitor. I’m not a fool, Ben; I know it was unwise, but love is often unwise. Your own father took a wife from England. What wisdom is that?”

I narrowly resisted the urge to cut his throat with a conveniently placed carving knife left on the tray in front of me. I took a deep breath and tried to blink away the reddish tinge across my vision. “Leave my mother out of it,” I said. Insults from Grandmother were one thing, but Romeo using my parentage to justify his own folly . . . “If the girl’s relatives don’t slaughter you in the streets, I’m certain that La Signora will order you manacled to a damp wall somewhere very deep, and have your madness exorcised with whips and hot irons. I’ll wager you won’t look fondly on your ladylove then.”

He was smart enough to realize that I was serious, and his drunken grin vanished, replaced by something that was much more acceptable: worry. “She’s just a girl,” he said. “No one takes it seriously.”

“Grandmother does, and so do many others. No doubt your fairest love has whispered it about the square as well.”

He grabbed me by the arm and pulled me closer, and his voice dropped to an intense whisper. “Ben, Rosaline wouldn’t betray me! Someone else, perhaps, but not Rosaline!”

I remembered her gilded in candlelight, watching me very levelly as I stole from her brother. She could have betrayed me. Should have, perhaps.

And she hadn’t.

“It doesn’t matter whose tongue wags,” I said. “She has servants paid to be sure she does nothing to dirty her family’s name . . . such as accepting poems from you. If her uncle hasn’t yet been told, it’s only a matter of time. It’s nothing to do with her. It’s how the world works.” I felt a little sorry for him. I couldn’t remember being that young, that ignorant of the consequences, but then, I was the son of a Montague who’d died on the end of a Capulet’s sword before I’d known him. I’d been raised knowing how seriously we played our war games of honor. “I pray you haven’t met her in secret.”

“She refused to come,” he said. “The verses were my voice in her ear. It was safer so.”

Safer. It seemed impossible for a man to be so innocent at the age of sixteen, but Romeo had indulgent parents, and a dreamer’s hazy view of responsibility.

“Your voice must go silent, then,” I said. “I’ll retrieve your love letters by any means necessary. Grandmother has given me orders.”

“But why would she send you to—” Drunk, it took a second more than necessary for the clue to dawn on him, and Romeo did a foolish imitation of shushing himself before he said, still too loudly, “I suppose the Prince of Shadows must go after them, being so well practiced in the art.”

“Oh, for the love of heaven, shut up!”

Not so far away, Montague and his wife were standing from table, as was my lady mother; we all rose to bow them off. As soon as they had achieved their exit, Romeo snapped back upright from his bow, turned to me, and took me fast by the shoulders. “Have I put Rosaline in danger?” He seemed earnestly concerned by it, an attitude that surely would not earn him praise from any other Montague . . . except, perhaps, from me. “Tell me true, coz; if they find my verses in her possession—”

“Sit,” I said, and shoved him. He collapsed into his chair with the boneless grace of someone well the worse for drink. “Eat your soup and clear your head. I’ll send for Mercutio. If risks must be taken, it’s better they’re shared.”

He spooned up soup, and gave me a loose, charming smile. “I knew you wouldn’t fail me, coz.”

• • •

Mercutio was a strong ally of Montague, but much more than that: He was my best friend, and Romeo’s as well. Mercutio had once refused to race off with my cousin, calling it a wild-goose chase, and Romeo had—rightly—declared that Mercutio was never there for us without also being there for the goose. In short, he was a brawler, a jester, and one other thing . . . the keeper of a great many secrets.

He kept mine, as the Prince of Shadows, and had for years, but his own secret was far more dire. He was in love, but his love, if discovered, would be more disastrous than Romeo’s failed flirtation. It was not simply unwise, but reckoned unnatural by Church and law alike.

I had never met the young man Mercutio adored, and hoped I never would; secrets of such magnitude were far easier to hold in ignorance. Romeo and I regularly sent notes to Mercutio’s family’s villa explaining his absences, pretended to be carousing with him while he slipped away in secret to a rendezvous. Upon occasion, when Mercutio was fully in his cups, we listened to his torment in never seeing his lover’s face in the light of day.

But those bouts of passionate longing were rare in him, and the Mercutio the world knew was a bright, sharp, hotly burning star of a man. He was widely admired for his willingness—nay, eagerness—to take risks others might call insane. Romeo and I knew where the roots of that dark impulse grew, but it never made us love him less.

This night, he might have knocked and cried friend at the palazzo doors and been granted an easy entry, but that was not exciting enough.

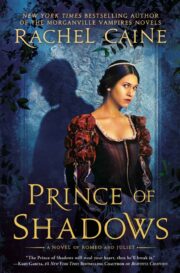

"Prince of Shadows" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Prince of Shadows". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Prince of Shadows" друзьям в соцсетях.