She found it almost impossible to tear her eyes away from the actors. How did they manage, so instinctively, to make themselves so interesting to watch? It was compelling viewing. She wanted to know everything about them, and yet oddly enjoyed this temporary stage of not knowing anyone well enough to be able to fix any significance to their actions. It was like watching a foreign film in glorious technicolour Without the subtitles. She didn't want to miss a moment of it. Her eyes were everywhere. She kept trying to turn her attention to the wallflowers like herself, but couldn't do it. The butterflies were too entrancing.

A tall, blond man wandered in, looking keenly at everyone, reminding Jazz of a big golden Labrador looking for a stick. He had twinkly blue eyes and rosy cheeks. She couldn't remember what play or programme she'd seen him in, but she knew his face well. He sat down on a chair by the wall opposite her and quietly studied a script. To her surprise, the woman in the brown jacket went over and joined him. She noticed that they were intimate enough not to need to talk to each other. The woman in the jacket was then joined by a shorter, less stunning friend, who was in turn accompanied by a man whose face had had a fight with gravity and lost.

What made the whole exercise so enjoyable for Jazz, was that for the first time ever, she was able to watch people without them minding. Usually, when she people-watched, she had to do it subtly - with quick sideways glances -otherwise people started to stare back. But these actors seemed to expect her stares; in fact, some of them were happily giving Jazz her own private performance. She wondered whether, if she got up and left the room, they would, en masse, collapse in a silent, audience-less heap on the floor, waiting for the next observer to come in so that they could start again. Naturally, not one of them was wasting any time looking at her unknown face.

Eventually, she tore her eyes away from them and looked towards the door. There she saw a face that made her innards shrink. It certainly wasn't an unpleasant face; in fact, Jazz could still see its charms, although now they left her cold. It was a smiling, unctuous face that she could now barely tolerate. Yet at the same time, by some obstinacy she didn't understand, she couldn't take her eyes off it. It was incongruously feminine, with pale skin and full red lips and cheeks, topped with a crop of dark hair, slicked forward into the newest French style with thick Brylcreem. Of course the mouth was upturned into a forced smile, but those eyes she knew so well were darting here and there; it was only a matter of time before they alighted on her. Still she couldn't look away. All too soon, the bright eyes met hers and Jazz only detected a nano-second of consideration before they were filled with careful warmth.

“Jasmin Field, I might have guessed you'd be here,” said Gilbert Valentine, ex-colleague and now self-important theatre journalist for a small, exclusive, self-important theatre magazine. Gilbert, she knew, always liked to think of himself as a superior sort of journalist - and, indeed, as a superior sort of person - but it was common knowledge that he used his privileged position, one that enabled him to get into previews and cast parties, to supplement a spin-off career as the tabloids' primary source of luvvie gossip. He didn't do it for the money, although the money was good; he did it because it gave him the kind of fame he craved. To be famous within the most desperate circle of fame-hunters was quite an achievement.

Gilbert Valentine was dangerous. When he had first entered the theatrical world, he had, chameleon-like, adopted a camp manner to endear him to his victims. He had never been able to shake it since. Gilbert was the only 100% straight man who minced like a true thespian. And like his manner, nothing about him could be trusted. He was the sort of journalist who gave journalists a bad name, and he put all actors in a no-win situation. If they didn't invite him to their parties, he got the gossip on them anyway, through fellow-actors anxious to get on his right side. So actors were forced to treat him as a friend, which for many of them was the most successful performance of their lifetime. However, it wasn't really difficult to butter Gilbert up. All one needed to do was natter his writing. Gilbert's Achilles' heel was his genuine insecurity about the quality of his work. He was the sort of man who couldn't wait until his obituary was published and all the quality newspapers would beat their chests for never utilising his genius themselves. It didn't occur to him that his obituary was already written and filed under T for Tosser.

“I didn't know you were an actor manqué!” he oozed patronisingly, as if Jazz's presence at the auditions was somehow more revealing than his. He came over and sat down next to her.

Jazz always found herself in the unhappy position of wanting to say to Gilbert, “Likewise”, but knowing that it would only belittle her. It was incredibly frustrating.

Instead she smiled and said simply, “Well, now you know everything.”

“Oh, hardly everything,” he simpered. “How are things at your lovely little women's mag?”

Jazz decided not to mention the trivial fact that Hoorah! her "little women's mag" had roughly three-quarters of a million more readers than his. Instead, she took a big breath and answered composedly, “Lovely thanks.”

“Oh good, good,” he smarmed.

“And how are things in the artistic world of theatre journalism?”

Gilbert sighed heavily, rubbed his eyes with his podgy, pale hands and just remembered in time not to brush them through his Brylcreemed hair. Jazz began to worry that he might be auditioning for the part of Darcy.

“Extremely harrowing. Nobody appreciates the work we do. But,” he admitted bravely, “I love it. Couldn't be without it.”

“Of course you couldn't.”

“Yes, you know me so well.”

Jazz nodded sadly.

He patted her hand. She moved it to scratch a suddenly itchy cheek.

“So tell me, what part do you want?” he asked.

Jazz laughed. “Oh, I'm just here for the experience.”

“Aha!” exclaimed Gilbert, pointing an accusing finger at her. “You're using it for copy in your column! "Working with Harry Noble." Like it! Well done, that girl! I did exactly that for a piece last year when they opened up auditions to the public for Where's My Other Leg? at the Frog and Whippet. It was a very, very funny piece. Very funny.”

Jazz impressed herself by managing a smile. She knew she didn't need to ask Gilbert why he was here. Just sitting in this church hall he had surrounded himself with people who were scared of him and could make him money at the same time. And she knew that deep down he had always wanted to be an actor, like so many arts journalists before him, and doubtless many after him.

“Of course,” said Gilbert silkily, “you do realise I almost know Harry Noble personally.”

Jazz raised her eyebrows questioningly and Gilbert needed no more prompting.

“Well, you know that his aunt, Dame Alexandra Marmeduke,” here Gilbert cast his eyes downwards as if she were dead, or a saint or something, “is the patron of our magazine? Without her, my life would have no purpose. No other publication, as you well know, has quite the same reverence for the theatre as we.” Jazz winced. “I owe her my livelihood and therefore my life. She's a spectacular woman. And her 1930s' Ophelia . . .” he closed his eyes as he savoured the memory “. . . was an all-time great. No one has ever surpassed it,” he whispered in hushed reverence.

Jazz nodded, wondering if that was the version where Ophelia wore a wig that looked like a dead octopus.

“But of course,” continued Gilbert, when he had quite recovered, “she and her nephew” - he paused for effect -“Do Not Speak.”

Jazz's eyes lit up. Inside information! “How come?” she asked.

“Didn't you know?” said Gilbert, delighted. Strictly speaking, he was aware that he shouldn't impart such a valuable piece of gossip to a fellow journalist without consulting terms first, but the temptation to impress Jazz proved irresistible. And anyway, it had always frustrated him that he could never actually make any money on this one - he couldn't risk Dame Alexandra finding out that he had been the source of such information. But, one day, who knew? He could receive payment of another kind from Jazz . . .

“Well, strictly entre nous,” he began, as he always did when about to sell a gem to a hack, “they had a furious family row years and years ago. That part's common knowledge within the theatrical world, but nobody - and I mean Nobody - knows the details quite like myself. Not many have had to visit Dame Marmeduke's Devon cottage. If I didn't work for that wonderful woman, I'd have sold this for a fortune, my dear. A fortune.”

Jazz started to grin mischievously and her eyes twinkled. She'd never heard this one.

Gilbert was just about to launch into the story when, to Jazz's extreme frustration, he sat back and stared at her, much in the same way one would eye a painting.

“You know, it's an absolute living, breathing joy to see you again,” he said, emphasising each word as if someone, somewhere, was writing down everything he said. “You look ravishing.”

Just when she thought she was going to have to get up and run out screaming, Jazz caught sight of her smiling sister George, coming towards her. She introduced George to Gilbert, hoping that somehow she could get him back to spreading malicious gossip and away from "joy", "ravishing" and, indeed, breathing.

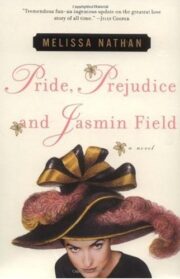

"Pride, Prejudice and Jasmine Field" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Pride, Prejudice and Jasmine Field". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Pride, Prejudice and Jasmine Field" друзьям в соцсетях.