He kissed her cheek lovingly. “It is. Ah, you mean the voyage!”

She laughed and put her arms over his.

“I was on the point of regretting the voyage when we were all afflicted with seasickness, but now I find myself wishing it would never end,” she said. “There is something invigorating about a life on the water.”

“This is just the start of things,” said Darcy. “Only a few more weeks, and we will be in Egypt.”

“Today it is all water, then it will be all sand!”

“And I have something to show you when we arrive.”

“Oh? And what might that be?”

He took evident satisfaction in her curiosity.

“Let us just say it is a surprise.”

***

While the others amused themselves on deck, Edward was in his cabin, poring over a print of the Rosetta Stone. He had been obsessed with its translation when it had first been discovered at the start of the century, but his interest had waned, only to be reawakened when he had found the map.

He became thoughtful as he relived the memory.

His father’s tales of Egypt had inspired him as a boy, and the thought of a map marking the spot of an undiscovered—and unplundered—tomb had fired his imagination. But his father had refused to let him examine the map, saying it was worthless and telling him not to waste his life on daydreams. So Edward had stopped talking to his father about Egypt, but he had not stopped visiting museums, reading about the latest findings, and collecting pottery.

And then, on a particularly rainy afternoon the previous winter, he had gone into the attic in search of a brace of pistols which had been taken there by mistake, and on a table in a wooden box he had found the map—or at least part of it, for it was incomplete. Nevertheless, there was enough to show that the tomb lay near a city and between two oases. His initial excitement had been dampened by the knowledge that Egypt was full of cities and oases and that his father had been unable to find the tomb despite a diligent search. He reminded himself that it would not be any different for him… until he saw that, along the top of the map, there were several rows of hieroglyphs. In his father’s time, there had been no hope of translating them. But now, with the discovery of the Rosetta Stone, it seemed that such a translation might be possible; and then the fabled tomb, with its fabled treasure, would be within his grasp.

And so he had written to some of the learned men who were working on translating the hieroglyphs and discovered enough to know that the city on the map was Cairo and not Luxor. Knowing that Sir Matthew Rosen was engaged on a dig in that area, he had arranged the meeting in London, hoping that he might be able to persuade Sir Matthew to allow him to join the dig. To his great excitement, Sir Matthew had agreed to his proposal. And what had excited him more had been the discovery that Sir Matthew had in his possession a frieze showing the likeness of Aahotep. The frieze, the doll, and the tomb were all linked, for his father had believed that the tomb was that of the young bridal couple Aahotep had supposedly poisoned.

He thought of the story again. Aahotep had murdered a pair of lovers in a jealous rage and they had been buried in a hidden tomb, protected by magical spells to ensure they would rest undisturbed. Strip away the fantastic story of magicians and spells, so beloved by the ancient Egyptians, and what was left was a down-to-earth tale of two wealthy people buried together in an undiscovered tomb. And he had a map to the whereabouts of the tomb.

But most exciting of all was the knowledge that Sir Matthew had discovered the frieze in a souk near Cairo, confirming that Cairo was indeed the city on the map, and not Luxor, as his father had thought. No wonder his father’s efforts to find it had been in vain!

For the first time, Edward felt he had a real chance of succeeding where his father had failed.

Visions of gold and jewels swam before his eyes… and then visions of himself bestowing them on Sophie Lucas. He had never met anyone like her. She was fragile and delicate and ethereal, and he thought her the most beautiful creature he had ever seen. When she spoke, he bent his head to listen, as if it was drawn to her by a string. Her deep sadness brought out all his chivalrous instincts and he found himself wanting to bring a smile to her beautiful face. And what better way to do it than to shower her with jewels and lay all his earthly possessions at her feet?

Pushing aside his books, he decided to take a turn on deck in the hope that Sophie might happen to be there as well.

***

Sophie was enjoying the open air and the Mediterranean sunshine. After a long, dark time, she was beginning to come to life again. The new sights and scents stimulated her, and the uncomplicated love of the Darcy children soothed her battered spirit, for although her own family had tried to help her, their constant attentions had depressed her spirits rather than otherwise. They had exhorted her to count her blessings, but this had only made her feel worse, because she then felt guilty for being ungrateful as well as feeling unhappy; they had told her to forget Mr Rotherham, which she had been unable to do; and they had reminded her that she must not leave it too long to return to the land of the living, for at the age of twenty-two she was in danger of becoming an old maid and could not delay her search for a husband. They had talked incessantly of her married sisters: Charlotte, with her comfortable rectory and three children, and Maria, with her handsome husband and her new baby. They had said that she must find the same—never realising that it was those very exhortations which had made her so vulnerable to the attentions of the handsome but fickle nephew of her father’s old business partner, Mr Rotherham, in the first place.

A fresh breeze sprang up and a sudden gust caught her bonnet, diverting her thoughts to the immediate task of keeping it on her head. She put her hand on it, catching it before it was ripped away, but her feather was not so lucky. It was torn loose by the wind and danced along the deck, whirling and pirouetting as it was blown toward the rail.

Laughing at the comical sight, she sprang up to chase after it, but Paul Inkworthy was quicker. Putting aside his sketch, he leapt up and caught it, handing it to her with a laugh and a bow.

Sophie blushed as she took it, feeling suddenly awkward. Mr Inkworthy was not handsome, but his eyes were kind and intelligent and there was no denying the fact that his evident admiration had done much to restore her confidence in recent weeks. But still she did not have the courage to speak.

“Miss Lucas…” said Paul, and then he stopped.

She willed him to continue but was not surprised when he did not. What could a young man such as Mr Inkworthy—for he was a year younger than she—have to say to a woman of her age? His kindness and gentleness were indisputable, but his admiration, she told herself, was of an artistic kind. But still she could not bring herself to walk back across the deck to her embroidery. And so she looked at him, willing him to continue, for she wanted to talk to him, but she had grown tongue-tied.

He lapsed into silence again and she felt a certain empathy with him. He, too, was shy and, she suspected, uncomfortably aware of his situation. His position was a difficult one. He was not a friend of the family nor yet quite a servant, and so he was an outsider to both parties. As, in a way, was she. For although the Darcys had invited her as their guest, she was considerably younger than Elizabeth, who had been a friend of her older sister Charlotte rather than a particular friend of hers, and she did not have the wealth or the position of the Darcys. Then, too, it was not always easy for her to talk to older people. True, there was another young man on board, for Edward was more of an age with her, but she did not encourage her feelings for him, as she knew too well how vulnerable a woman made herself when she entertained feelings for a rich and handsome man.

The silence was becoming awkward and so she turned to go but, emboldened by her step toward departure, Paul said, “I have no right…”

She stopped and waited for him to continue.

“I have no right,” he said again and then went on in a rush, “but I cannot bear to see you so sad. I know I should not talk of it, but I can think of nothing else to talk to you about, except commonplaces, and I do not want to bore you with my feeble attempts to talk about the weather. Something has happened to you, I can tell that, something which has robbed you of your happiness. I just wanted to know if there was anything I could do for you. If I might be of service to you in any way—even if it is only to listen—well, then, I would gladly do anything in my power to lighten your burden.”

He spoke with such obvious sincerity that Sophie found herself wanting to confide in him. She had tried to speak to her siblings at the time, but they had been busy with their own affairs and inclined to dismiss the feelings of the youngest member of the family. Her parents had had time and interest aplenty but no way of understanding her.

“There was an unhappy love affair, I think,” he said, not looking at her but instead looking over the sea.

It made it easier for her.

“There was someone…” she said, not knowing how to begin but nevertheless wanting to speak.

“In Hertfordshire?” he asked, looking back toward her. “That is where you are from, I think?”

She nodded. “Yes.” And then she stopped, for she did not know how to go on.

“I have never been to Hertfordshire, but I hear it is very pretty.”

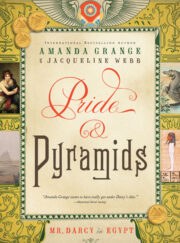

"Pride and pyramids : Mr. Darcy in Egypt" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Pride and pyramids : Mr. Darcy in Egypt". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Pride and pyramids : Mr. Darcy in Egypt" друзьям в соцсетях.