Melissa shook her head. ‘You don’t understand, Spence – it’s soooooo much work. When I was president, I barely had time for anything else!’

‘You do have quite a few activities, Spencer,’ Mrs. Hastings murmured. ‘There’s yearbook, and all those hockey games . . .’

‘Besides, Spence, you’ll take over if the president, you know . . . dies.’ Melissa winked at her as if they were sharing this joke, which they weren’t.

Melissa turned back to her parents. ‘Mom. I just got the best idea. What if Wren and I stayed in the barn? Then we’d be out of your hair.’

Spencer felt as if someone had just kicked her in the ovaries. The barn?

Mrs. Hastings put her French-manicured finger to her perfectly lipsticked mouth. ‘Hmm,’ she started. She turned tentatively to Spencer. ‘Would you be able to wait a few months, honey? Then the barn will be all yours.’

‘Oh!’ Melissa laid down her fork. ‘I didn’t know you were going to move in there, Spence! I don’t want to cause problems—’

‘It’s fine,’ Spencer interrupted, grabbing her glass of ice water and taking a hearty swallow. She willed herself not to throw a tantrum in front of her parents and Perfect Melissa. ‘I can wait.’

‘Seriously?’ Melissa asked. ‘That’s so sweet of you!’

Her mother pressed her cold, thin hand against Spencer’s and beamed. ‘I knew you’d understand.’

‘Can you excuse me?’ Spencer dizzily shoved her seat back from the table and stood up. ‘I’ll be right back.’ She walked across the boat’s wooden floor, down the carpeted main stairs, and out the front entrance. She needed to get to dry land.

Out on the Penn’s Landing walkway, the Philadelphia skyline glittered. Spencer sat down on a bench and breathed yoga fire breaths. Then she pulled out her wallet and started to organize her money. She turned all the ones, fives, and twenties in the same direction and alphabetized them according to the long letter-number combination printed in green in the corners. Doing this always made her feel better. When she finished, she gazed up at the ship’s dining deck. Her parents faced the river, so they couldn’t see her. She dug through her tan Hogan bag for her emergency pack of Marlboros and lit one.

She took drag after angry drag. Stealing the barn was evil enough, but doing it in such a polite way was just Melissa’s style – Melissa had always been outwardly nice but inwardly horrid. And no one could see it but Spencer.

She’d gotten revenge on Melissa just once, a few weeks before the end of seventh grade. One evening, Melissa and her then-boyfriend, Ian Thomas, were studying for finals. When Ian left, Spencer cornered him outside by his SUV, which he’d parked behind her family’s row of pine trees. She’d merely wanted to flirt – Ian was wasting all his hotness on her plain vanilla, goody-two-shoes sister – so she gave Ian a peck good-bye on the cheek. But when he pressed her up against his passenger door, she didn’t try to run away. They only stopped kissing when his car alarm started to blare.

When Spencer told Alison about it, Ali said it was a pretty foul thing to do and that she should confess to Melissa. Spencer suspected Ali was just pissed because they’d had a running competition all year over who could hook up with the most older boys, and kissing Ian put Spencer in the lead.

Spencer inhaled sharply. She hated being reminded of that period of her life. But the DiLaurentises’ old house was right next door to hers, and one of Ali’s bedroom windows faced one of Spencer’s – it was like Ali haunted her 24/7. All Spencer had to do was look out her window and there was seventh-grade Ali, hanging her JV hockey uniform right where Spencer could see it or strolling around her bedroom gossiping into her cell phone.

Spencer wanted to think she’d changed a lot since seventh grade. They’d all been so mean – especially Alison – but not just Alison. And the worst memory of all was the thing ... The Jenna Thing. Thinking of that made Spencer feel so horrible, she wished she could erase it from her brain like they did in that movie Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

‘You shouldn’t be smoking, you know.’

She turned, and there was Wren, standing right next to her. Spencer looked at him, surprised. ‘What are you doing down here?’

‘They were . . .’ He opened and closed his hands at each other, like mouths yapping. ‘And I have a page.’ He pulled out a BlackBerry.

‘Oh,’ Spencer said. ‘Is that from the hospital? I hear you’re a big-time doctor.’

‘Well, no, actually, I’m only a first-year med student,’ Wren said, and then pointed at her cigarette. ‘You mind if I have a bit of that?’

Spencer twisted the corners of her mouth up wryly. ‘You just told me not to smoke,’ she said, handing it over to him.

‘Yeah, well.’ Wren took a deep drag off the cigarette. ‘You all right?’

‘Whatever.’ Spencer wasn’t about to talk things over with her sister’s new live-in boyfriend who’d just stolen her barn. ‘So where are you from?’

‘North London. My Dad’s Korean, though. He moved to England to go to Oxford and ended up staying. Everyone asks.’

‘Oh. I wasn’t going to,’ Spencer replied, even though she had thought about it. ‘How’d you and my sister meet?’

‘At Starbucks,’ he answered. ‘She was in line in front of me.’

‘Oh,’ Spencer said. How incredibly lame.

‘She was buying a latte,’ Wren added, kicking at the stone curb.

‘That’s nice.’ Spencer fiddled with her pack of cigarettes.

‘This was a few months ago.’ He raggedly took another drag, his hand shaking a little and his eyes darting around. ‘I fancied her before she got the town house.’

‘Right,’ Spencer said, realizing he seemed a little nervous. Maybe he was tense about meeting her parents. Or was it moving in with Melissa that had him on edge? If Spencer were a boy and had to move in with Melissa, she’d throw herself off Moshulu’s crow’s nest into the Schuylkill River.

He handed the cigarette back to her. ‘I hope it’s okay that I’m going to be staying in your house.’

‘Um, yeah. Whatever.’

Wren licked his lips. ‘Maybe I can get you to kick your smoking addiction.’

Spencer stiffened. ‘I’m not addicted.’

‘Sure you’re not,’ Wren answered, smiling.

Spencer shook her head emphatically. ‘No, I’d never let that happen.’ And it was true: Spencer hated feeling out of control.

Wren smiled. ‘Well, you certainly sound like you know what you’re doing.’

‘I do.’

‘Are you that way with everything?’ Wren asked, his eyes shining.

There was something about the light, teasing way he said it that made Spencer pause. Were they . . . flirting? They stared at each other for a few seconds until a big group of people came whooshing off the boat onto the street. Spencer lowered her eyes.

‘So, do you think it’s time we go back?’ Wren asked.

Spencer hesitated and looked at the street, full of taxis, ready to take her wherever she wanted. She almost wanted to ask Wren to get in one of the cabs with her and go to a baseball game at Citizens Bank Park, where they could eat hot dogs, yell at the players, and count how many strikeouts the Phillies’ starting pitcher racked up. She could use her dad’s box seats – they mostly just went to waste, anyway – and she bet Wren would be into that. Why go back in, when her family was just going to continue to ignore them? A cab paused at the light, just a few feet from them. She looked at it, then back at Wren.

But no, that’d be wrong. And who would fill the vice president’s post if he died and she was murdered by her own sister? ‘After you,’ Spencer said, and held the door open for him so they could climb back aboard.

Starts and Fitz

‘Hey! Finland!’

On Tuesday, the first day of school, Aria walked quickly to her first-period English class. She turned to see Noel Kahn, in his Rosewood Day sweater vest and tie, jogging toward her. ‘Hey.’ Aria nodded. She kept going.

‘You bolted from our practice the other day,’ Noel said, sidling up next to her.

‘You expected me to watch?’ Aria looked at him out of the corner of her eye. He looked flushed.

‘Yeah. We scrimmaged. I scored three goals.’

‘Good for you,’ Aria deadpanned. Was she supposed to be impressed?

She continued down the Rosewood Day hallway, which she’d unfortunately dreamed about way too many times in Iceland. Above her were the same eggshell-white, vaulted ceilings. Below her were the same farmhouse-cozy wood floors. To her right and left were the usual framed photos of stuffy alums, and to her left, incongruous rows of dented metal lockers. Even the very same song, the 1812 Overture, hummed through the PA speakers – Rosewood played between-classes music because it was ‘mentally stimulating.’ Sweeping by her were the exact same people Aria had known for a gazillion years . . . and all of them were staring.

Aria ducked her head. Since she’d moved to Iceland at the beginning of eighth grade, the last time everyone had seen her she was part of the grief-stricken group of girls whose best friend freakishly vanished. Back then, wherever she went, people were whispering about her.

Now, it felt like she’d never left. And it almost felt like Ali was still here. Aria’s breath caught in her chest when she saw a flash of blond ponytail swishing around the corner to the gym. And when Aria rounded the corner past the pottery studio, where she and Ali used to meet between classes to trade gossip, she could almost hear Ali yelling, ‘Hey, wait up!’ She pressed her hand to her forehead to see if she had a fever.

‘So what class do you have first?’ Noel asked, still keeping pace with her.

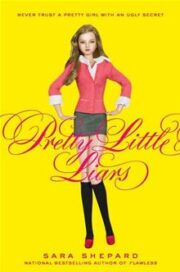

"Pretty Little Liars" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Pretty Little Liars". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Pretty Little Liars" друзьям в соцсетях.