And then, only a half hour ago, Spencer had watched her dad’s Jaguar back out of the driveway and turn toward the main road. Her mom was in the passenger seat; Melissa was in the back. She had no idea where they were going.

She slumped down in her computer chair and pulled up that first e-mail from A, the one talking about coveting things she couldn’t have. After reading it a few times, she clicked REPLY. Slowly she typed, Are you Alison?

She hesitated before hitting SEND. Were all the police lights making her trippy? Dead girls didn’t have Hotmail accounts. Nor did they have Instant Messenger screen names. Spencer had to get a grip – someone was pretending to be Ali. But who?

She stared up at the Mondrian mobile she’d bought last year at the Philadelphia Art Museum. Then she heard a plink sound. There it was again.

Plink.

It sounded really close, actually. Like at her window. Spencer sat up just as a pebble hit her window again. Someone was throwing rocks.

A?

As another rock hit, she went to the window – and gasped. On the lawn was Wren. The blue and red lights from the police cars kept making streaky shadows across his cheeks. When he saw her, he broke into a huge smile. Immediately, she bolted downstairs, not caring how horrible her hair looked or that she was wearing marinara-stained Kate Spade pajama pants. Wren ran for her as she came out the door. He threw his arms around her and kissed her scruffy head.

‘You’re not supposed to be here,’ she murmured.

‘I know.’ He stood back. ‘But I noticed your parents’ car was gone, so...’

She pushed her hand through his soft hair. Wren looked exhausted. What if he had to sleep in his little Toyota last night?

‘How did you know I’d be back in my old room?’

He shrugged. ‘A hunch. I also thought I saw your face at the window. I wanted to come earlier, but there was . . . all that.’ He gestured to the police cars and random news vans next door. ‘You okay?’

‘Yeah,’ Spencer answered. She tilted her head up to Wren’s mouth and bit her chapped lip to keep from crying. ‘Are you okay?’

‘Me? Sure.’

‘Do you have somewhere to live?’

‘I can stay on a friend’s couch until I find something. Not a big deal.’

If only Spencer could stay on a friend’s couch too. Then something occurred to her. ‘Are you and Melissa over?’

Wren cupped her face in his hand and sighed. ‘Of course,’ he said softly. ‘It was kind of obvious. With Melissa, it wasn’t like . . .’

He trailed off, but Spencer thought she knew what he was going to say. It wasn’t like being with you. She smiled shakily and laid her head against his chest. His heart thumped in her ear.

She looked over at the DiLaurentis house. Someone had started a little shrine to Alison on the curb, complete with pictures and Virgin Mary candles. In the center were little alphabet magnet letters that spelled Ali. Spencer herself had propped up a smiling picture of Alison in a tight blue Von Dutch T-shirt and spanking new Sevens. She remembered when she’d taken that picture: They were in sixth grade, and it was the night of the Rosewood Winter Formal. The five of them had spied on Melissa as Ian picked her up. Spencer had gotten hiccups from laughing when Melissa, trying to make a grand entrance, tripped down the Hastingses’ front walk on the way to the tacky rented Hummer limo. It was probably their last really fun, carefree memory. The Jenna Thing happened not too long after. Spencer glanced at Toby and Jenna’s house. No one was home, as usual, but it still made her shiver.

As she blotted her eyes with the back of her pale, thin hand, one of the news vans drove by slowly, and a guy in a red Phillies cap stared at her. She ducked. Now would not be the time to capture some emotional-girl-breaks-down-at-thetragedy footage.

‘You’d better go.’ She sniffed and turned back to Wren. ‘It’s so crazy here. And I don’t know when my parents will be back.’

‘All right.’ He tilted her head up. ‘But can we see each other again?’

Spencer swallowed, and tried to smile. As she did, Wren bent down and kissed her, wrapping one hand around the back of her neck and the other around the very spot on her lower back that, just Friday, hurt like hell.

Spencer broke away from him. ‘I don’t even have your number.’

‘Don’t worry,’ Wren whispered. ‘I’ll call you.’

Spencer stood out on the edge of her vast yard for a moment, watching Wren walk to his car. As he drove away, her eyes stung with tears again. If only she had someone to talk to – someone who wasn’t banned from her house. She glanced back at the Ali shrine and wondered how her old friends were dealing with this.

As Wren pulled to the end of her street, Spencer noticed another car’s headlights turn in. She froze. Was that her parents? Had they seen Wren?

The headlights inched closer. Suddenly, Spencer realized who it was. The sky was a dark purple, but she could just make out Andrew Campbell’s longish hair.

She gasped, ducking behind her mother’s rosebushes. Andrew slowly pulled his Mini up to her mailbox, opened it, slid something in, and neatly closed it again. He drove away.

She waited until he was gone before sprinting out to the curb and wrenching open the mailbox. Andrew had left her a folded-up piece of notepaper.

Hey, Spencer. I didn’t know if you were taking any calls. I’m

really sorry about Alison. I hope my blanket helped you yesterday.

—Andrew

Spencer turned up her driveway, reading and rereading the note. She stared at the slanty boy handwriting. Blanket? What blanket?

Then she realized. It was Andrew who helped her?

She crumpled up the note in her hands and started sobbing all over again.

Rosewood’s Finest

‘Police have reopened the DiLaurentis case, and are in the process of questioning witnesses,’ a newscaster on the eleven-o’clock news reported. ‘The DiLaurentis family, now living in Maryland, will have to face something they’ve tried to put behind them. Except now, there is closure.’

Newscasters were such drama queens, Hanna thought angrily as she shoved another handful of Cheez-Its in her mouth. Only the news could find a way to make a horrible story worse. The camera stayed focused on the Ali shrine, as they called it, the candles, Beanie Babies, wilted flowers people no doubt just picked out of neighbors’ gardens, marshmallow Peeps – Ali’s favorite candy – and of course photos.

The camera cut to Alison’s mother, whom Hanna hadn’t seen in a while. Besides her teary face, Mrs. DiLaurentis looked pretty – with a shaggy haircut and dangly chandelier earrings.

‘We’ve decided to have a service for Alison in Rosewood, which was the only home Ali knew,’ Mrs. DiLaurentis said in a controlled voice. ‘We want to thank all of those who helped search for our daughter three years ago for their enduring support.’

The newscaster came back on the screen. ‘A memorial will be held tomorrow at the Rosewood Abbey and will be open to the public.’

Hanna clicked off the TV. It was Sunday night. She sat on her living room couch, dressed in her rattiest C&C T-shirt and a pair of Calvin Klein boxer briefs she’d pilfered out of Sean’s top drawer. Her long brown hair was messy and strawlike around her face and she was pretty sure she had a pimple on her forehead. A huge bowl of Cheez-Its rested in her lap, an empty Klondike wrapper was crumpled up on the coffee table, and a bottle of pinot noir was wedged snugly at her side. She’d been trying all night not to eat like this but, well, her willpower just wasn’t very strong today.

She clicked the TV back on, wishing she had someone to talk to . . . about the police, about A, and mostly about Alison. Sean was out, for obvious reasons. Her mom – who was on a date right now – was her usual useless self. After the hubbub of activity at the police station yesterday, Wilden told Hanna and her mother to go home; they’d deal with her later, since the police had more important things to attend to at the moment. Neither Hanna nor her mom knew what was happening at the station, only that it involved a murder.

On the drive home, instead of Ms. Marin reprimanding Hanna for, oh, stealing a car and driving piss-drunk, she told Hanna that she ‘was taking care of it.’ Hanna didn’t have a clue what that meant. Last year, a cop had spoken at a Rosewood Day assembly about how Pennsylvania had a ‘zero tolerance’ rule for drunk drivers under twenty-one. At the time, Hanna had paid attention only because she thought the cop was sort of hot, but now his words haunted her.

Hanna couldn’t rely on Mona, either: She was still at that golf tournament in Florida. They’d spoken briefly on the phone, and Mona had admitted the police had called her about Sean’s car, but she’d played dumb, saying she’d been at the party the whole time and Hanna had been too. And the lucky bitch: They’d gotten the back of her head on the Wawa surveillance tape, but not her face, since she’d been wearing that disgusting delivery hat. That was yesterday, though, after Hanna got back from the police station. She and Mona hadn’t talked today, and they hadn’t discussed Alison yet.

And then . . . there was A. Or if A was Alison, would A be gone now? But the police said Alison had been dead for years . . .

As Hanna scanned the guide feature on TV for what else was on, her eyelids swollen with tears, she considered calling her father – this story might be on the Annapolis-area news, too. Or maybe he’d call her? She picked up the silent phone to make sure it was still working.

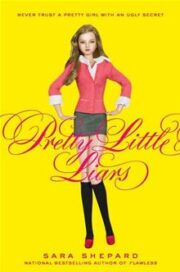

"Pretty Little Liars" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Pretty Little Liars". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Pretty Little Liars" друзьям в соцсетях.