I don’t see my parents’ faces, don’t wonder if they are horrified or mortified or both, because I can’t look at them and watch all the respect they had for me drain away before my eyes.

I try to be a grown-up. I attempt to say it all with no emotion, without showing how terrified I am of these questions. The detail is astounding—in McMillan’s wording and how much I’m supposed to reveal in my response. I have to close my eyes sometimes, shut out everyone in the room and talk like I’m relaying the plot of a movie. I don’t shake so much if I think about someone else in the role of Theo Cartwright. My voice wavers a few times, but McMillan just tells me to take my time, waits patiently as I stop to take in a few deep breaths or sip from my water.

Chris’s lawyer isn’t so nice. He spits questions at me rapidly, so quickly that my body grows too warm and my thoughts become muddled. But I keep up with him. I have to, because the sooner I answer his questions, the sooner I can get out of this hard seat and away from all these probing eyes. His own are an icy, crystal blue and they peer at me the whole time he’s cross-examining, daring me to doubt him. I knew from the second I saw him that he’d be anything but easy on me. He keeps asking if Chris ever flat-out told me he was going away with Donovan, or if I ever saw anything inappropriate between them with my own eyes. He asks if Chris threatened me, if I ever felt like my life was in danger when I was around him.

McMillan objects a few times—maybe one time too often, because the judge admonishes him and almost seems ready for Chris’s lawyer to get back to it. But I appreciate that he’s looking out for me, that he knows how hard it is to sit in front of a courtroom and have my past laid bare.

I glance at Chris a few times and it’s hard to believe how the tables have turned. It feels amazing to have the power over him, and I become stronger as he sinks a little lower into his seat with each admission. He’s done. Ruined. And maybe my life is, too, but at least I’m not going down alone.

I wonder when he decided—that it was going to be me, and then Donovan, for as long as he could have him. Did he know how it would play out as soon as we stepped through the front door of Big Red’s? Or did he wait a few days to feel us out?

I think the part that bothers me the most is not knowing if he’d targeted us specifically or if he would have done the same thing to any two kids who walked through the door.

I don’t want him to have that choice ever again and that’s how I pull through the questions from Chris’s attorney. Even the hateful ones that imply I was stupid and probably deserved what I got.

Maybe he thinks that. A lot of people might think that when they find out. But I told the truth. I did what I could for Donovan and people can call me all the names they want, but selfish won’t be one of them.

CHAPTER THIRTY

I SLEEP FOR WHAT FEELS LIKE A WEEK, BUT WHEN I

finally get out of bed it’s only four in the morning.

I’m groggy. Disoriented. I crawled into bed as soon as we got home from the courthouse, and the trial comes flooding back in a rush.

The defense attorney’s accusing tone as he fired the most embarrassing, personal questions at me. Questions no one should ever have to hear, let alone answer in front of a crowd. The hushed sounds of shock from the gallery. Chris’s eyes. Always Chris’s eyes.

McMillan and the suits escorted us to our car, protected us from the throng of reporters shouting questions and shoving microphones in our faces. We made it home in record time only to find the same type of scene outside of our house. Once we were inside safely, I walked directly to the stairs. I hadn’t said a word to either of my parents since I stepped off the stand.

They talked to me, though. Even when I didn’t talk back, they kept going. They must have said they loved me no fewer than twenty times on the drive back, then assured me it wasn’t my fault, that I should never think it’s my fault. They told me that what I did was brave, that they were proud of how grown up I was on the stand.

Dad chimed in, but Mom did most of the talking. I wondered why, until I saw his eyes when he opened the car door for me. They were red and watery and he’d been hiding his tears from me the whole ride home.

I turn on my light and look down at myself. I’m still in all the clothes I wore to the trial: black pants and a gray blouse that reminds me of Hosea’s eyes. My black cardigan lies on the floor next to my flats. My phone sits on top of my dresser across the room, turned off as soon as I got home. I couldn’t take any chances. I still can’t. Everyone must know the news by now.

I think of the reporters who greeted us on our trip back from the courthouse and I jump back over to the wall, slam my hand down against the light switch. I wait for my eyes to readjust to the dark, then creep slowly to the window. I crouch down so my eyes are level with the ledge and I slowly part the curtains, look out at the dark street below.

Still there. Not as many as before, and they’re not standing outside, but a couple of vans are parked across the street. One is planted boldly in front of our house. I can’t make out any shapes inside the tinted windows, but I can only imagine the men inside. Leaned back in the seats with their mouths open as their snores fill the cabin, or heads slumped over chests as they try to catch a few winks. They can’t miss anything. For many, this is probably their biggest story yet and it was delivered straight to them, practically on a silver platter.

I pad downstairs to the kitchen in the dark and open the refrigerator, casting a halo of light around my face. Boiled eggs. Leftover macaroni and cheese—homemade, not from the box. A couple of aluminum-foil-wrapped slabs catch my attention. I peel off the top layer of foil, look down to discover leftover slices of frozen pizza.

I close the fridge and open the pantry. My eyes skim over bags of potato chips and boxes of fancy crackers and the package of British cookies my father loves. (“They’re biscuits,” he says in a bad accent every time he pulls out the package, just to annoy me and Mom.) Things I haven’t touched in months, can barely remember the taste of. My stomach growls but I can’t eat. I haven’t eaten anything since the granola bar yesterday morning and most of that sits in the silver trash can across the room.

Maybe I’ll never eat again. Maybe I’ll just waste away in front of everyone because that seems like the easiest choice now. My ballet career—or the promise of one—is over. My friends must be furious at me for keeping such a huge secret from them. And Hosea . . . Well, he didn’t choose me anyway, but now he must be glad he didn’t end up with a girl who’d been sleeping with a pedophile.

I slip back upstairs, where I walk into the bathroom and turn on the shower. It’s likely to wake my parents but the hot water shooting down on me is just the right kind of pain and I stay in until the skin on my fingers prunes.

When I come out of the bathroom wrapped in a towel, a triangular beam of light peeks out from the door of Mom and Dad’s room. It’s cracked, just slightly. I pause in the space between our rooms, wonder if they’ll call out to me. A couple of seconds later, Dad’s muffled voice says, “You okay, babygirl?”

“Do you need anything, honey?” Mom asks.

I hear a pair of feet drop to the floor.

“I’m fine,” I say. “I’m going back to bed now.”

A long pause, then, “Okay, sweetheart. We’ll be right here if you need us.”

“We love you,” Dad calls out before I shut my door.

I change into a fresh pair of pajamas, dressing in the dark, and get back into bed, feeling worse than I did forty-five minutes ago.

Two minutes later I get back out and walk into their room without knocking. They won’t care. They’ve wanted me to talk to them for hours now. Mom is sitting up in bed, her back propped against their nest of pillows. Dad is pacing the room in flannel pants and a T-shirt. They were murmuring before I walked in, but they stop. Smile at me, gesture me in from the doorway. I stand in place.

“Sweetie?”

Mom’s voice is soft. Tentative. Comfort. Love. All of the reasons I can’t respond.

Dad walks toward me, says: “Can’t shut off your brain, babygirl?” His voice is decidedly upbeat—even if it’s forced—but I suspect from the bags under his eyes that he hasn’t slept much tonight, if at all.

I shake my head. I know the routine. Yet I don’t walk over to their bed and slip under the sheets between them, lying there as my mother strokes my hair and tells me everything will be all right. I yearn for their soothing voices, would like nothing more than to fall asleep to their placating words.

I lean against the doorframe for support, close my eyes for a moment to trigger the memories of that summer. Things could be different this time. It could be a totally different experience, knowing what I do now and I have to at least try because I’m not sure being here is an option.

I pinch my thumb and forefinger around the skin on my waist. Skin suctioned like glue to muscle and bone.

“I think I need to go back to Juniper Hill.”

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

THE HOUSE LOOKS COZIER WHEN WE PULL UP THIS TIME, BUT maybe it’s because of the snow blanketing the peaks of the Victorian architecture like a real-life gingerbread house.

It’s strange to walk up the steps in snow boots, to stamp the soles on the rough fibers of the welcome mat as we wait for someone to come to the door. Last time the air was thick and hot, the landscape buzzing with insects and fat bees that swooped in front of our faces. This time I can see my breath.

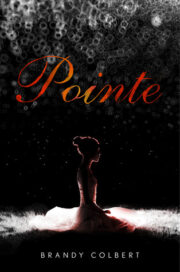

"Pointe" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Pointe". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Pointe" друзьям в соцсетях.