I see them as soon as I’m around the bend on Cypress. Beyond the spire of First Parish, beyond the snowy lawn of the old burying ground, a cluster of mourners has gathered around a fresh grave. Even considering the weather, this funeral seems paltry. I pause a moment to watch before I continue into the church.

Though Aunt Clara flung it as an accusation and is too much of a goose to know if it’s true or not, she is correct. My father was an Universalist. When he was alive, we occasionally attended services. I feel more lapsed than blasphemous, though, as I enter First Parish, where I slide into a pew in back. But this morning I crave something different from prayers and hymns. I need the breath of Will’s spirit. I need him before me. My heart aches with hope.

I open my Bible to my selected passage. My lips silently mouth the words of the ancient prayer. “Grant, O Lord, to Thy servant departed, that he may not receive in punishment the requital of his deeds. May Thy mercy unite him above to the choirs of angels.”

I’ve slid both of Geist’s prints into the book to mark the page. Viviette’s crown of irises and the heart on my breastbone are

Will’s communication in plain sight. “I forgive any crimes you’ve committed, Will,” I whisper, “and I promise that I’ll wear my necklace always, to honor our love and your memory. I’m glad you led my way to it.” There.

From my perch at the edge of the pew, I watch the drift of dust motes caught in the sunbeam through the stained-glass windows. It is mesmerizing, light and dust creating a reminder that God’s beauty is all around us.

I’ve been so eager for a sign. The fever again. The undertow. Nothing comes. After a few minutes I allow myself a peek around me. The faces of the congregation are hard in their unfamiliarity, and the air feels strained with other peoples’ fervor. We worship in unison, but our troubles are all our own.

Why did I think Will would be here? Will, who preferred a Sunday picnic to a Sunday service. Disappointment eddies through me. How stupid, really, to believe that church was a consecrated space for him. My attention falters through the rumble of the sermon, the recitations, prayers, and song. Will is like a dream just out of my reach.

A final processional hymn and the service is over. I’m first to go. Outside, walking under the dripping yews, I see mourners trudging back from the burial. Among them I see Wigs, the barkeep from the Black Iris.

I stop and shade my eyes to get a better look. Though protected by the hood of his mackintosh, Wigs feels my watch on him. He looks up, his fish mouth agog, as I dart to the cemetery gates.

“Eh. Didn’t even bother to pay a last regard? Least you might’ve done.” He grasps the top of the gate and knocks the toe of one boot and then the other against the iron rail to dislodge the snow. “Though the boy said you weren’t his Frances, after all, he called you a friend. ’Tain’t much of one, in my eyes. Got your servant girl to send a chicken soup, and a call from your fancy doctor, who couldn’t do no more for him than our own Norris. So I guess your conscience is clean.”

“That burial was Private Dearborn’s?”

“Don’t play innocent with me, Miss.” Wigs shakes a handkerchief from his pocket and blows his nose wetly into it.

“I didn’t…” I stare across to the farthest, snowy reach of the cemetery, bordered by pines. A lone figure stands at the grave.

Even from that far away, I can see that it’s Quinn.

“He went quick.” A harried young woman, her hair halfunbundled and her face tinged with cold, has come to stand next to Wigs. A child clinging behind her wipes his nose on her skirts. “He came down with fever Tuesday morning, died Friday, and was buried today.” She looks kinder than her father. She turns to him now. “Best to hurry, Fa. I’ve got the stew on.”

“Are you the one who cared for Nate?” I ask.

“I am. I’m Sue.” When she smiles, shyness turns her face even rosier.

“Not that it makes a whit of difference to you,” Wigs adds in his blunt, bullying way, “who didn’t share that burden at all.”

“I’m sorry, but I didn’t really know him.” I catch my breath and then say, awkwardly, “My name is Jennie Lovell. Nate Dearborn was in the same regiment as my fiancé, William Pritchett. He was killed this summer in battle at the Wilderness, in Virginia. I hadn’t met Nate until last week, but I’d like to pay my condolences to the boy’s family all the same. Are they here?”

My words have caused Sue’s eyes to round like an otter’s, and I sense a change in Wigs’s manner, too. “No, Miss, there’s no family,” she answers faintly. “We telegraphed to Pittsfield to notify his kin. Seemed he hadn’t anyone close, though a cousin did telegraph back. ’Twas a most distressing communication. He’d thought the boy’d been dead for months. In fact, he’d had a captain’s telegram this past summer that stated Nate had fallen in battle. In the Wilderness. Just like your William.” She concentrates her stare on me, awaiting some clarification.

“The records of the fallen are sometimes painfully inaccurate,” I note. But my mind is reeling. It’s too much a coincidence.

“He’d been lucky to have died in battle,” adds Wigs, whose disapproval toward me seems to have neutralized with my explanation.

“Least it’d been over quick.”

“Pyemia is the name the doctor gave it. An infection that got in Nate’s blood after the amputations.” Sue hoists the child to her hip. “Such suffering in that boy’s short life.”

I murmur sympathies, but then have to ask, “Did the cousin in Pittsfield give you the captain’s name? The one who signed the death notice?”

Sue taps her fingers to her lips. “There was a name, but I can’t recall.”

“James Fleming, perhaps?”

“That’s it, yes.” Sue nods. “He was commander to your fiancé, too?”

“He was.” Out of the corner of my eye, I watch Quinn exit the cemetery, skirting through to a shortcut that leads to the wooded trail back home.

“It’s a forgiving commander who allows folk to think their boy fell on the field,” says Wigs. “There’s honor in it. For your fiancé, too, I’d warrant.”

It is an almost audible click into place. Of course. In one powerful signature, Fleming bestowed legitimacy on the captured men of his company. The grace of a death in combat, so that families wouldn’t suffer to learn the horror of death in prison. What did Nate say? Slipped the noose. Nate Dearborn was supposed to be dead. My stomach lurches. Quinn would never confess it, but he might confirm it.

First I’ll need to catch up with him, though. Before he locks himself in his room or disappears for the rest of the day.

“Excuse me, then.” To Sue, “Very glad to meet you.” To Wigs, “Good day, sir.” And I peel off as fast as my muddy boots can take me.

Quinn has kicked a path through the snow, which helps my own journey, but he has a lead by a few minutes. When I reach the bend and shout his name, I can feel him startle, though he keeps his pace.

“Where are you coming from?” He looks suspicious. “Are you spying on me?”

“Spying on you?” I try a laugh, which falters. “’Course not. Why would I be?”

He doesn’t answer, but his answering scowl reminds me of a particular day, years ago, when Toby and I’d first arrived at Pritchett House. Exuberant, Will had taken me in hand at once, eager to show off all his home’s delights from Uncle’s ivory menagerie to the lions carved in the parlor fireplace, and the Dresden jar where Aunt kept her digestive peppermints.

Quinn had followed from an aloof distance. Every moment we’d waited for him to turn his heel altogether. As if we were hunting him. “Best not to spy on cousin Quinn for a while,” Toby had decreed in those early days. “His guard is high as ours.” His guard is up now.

“I’m not spying at all,” I promise. “But I saw you at Nate Dearborn’s burial.”

Quinn’s silence speaks to his uncertainty.

“You were in the Twenty-eighth together,” I continue. “In fact, you’d sent away a messenger a few weeks ago to prevent me from talking to him. But I found him anyway.”

“However you know him, let me assure you, Dearborn wasn’t fit for your company,” Quinn retorts. “I’m paying for his tombstone as an anonymous gift, so he and I are square but he wasn’t welcome in Brookline. Not by me, anyway. He ought to have stayed on that train and gone all the way home.” He pivots and starts to walk, but I won’t let him outpace me.

“Nate was hiding something shameful from his family, and you know it. Stop lying, Quinn, it’s no service to me Will’s letter confessed more than you’d ever want me to know.”

He halts so suddenly that I almost careen into him. He turns. Behind the steely freeze of his face lives the truth. I am sure of it.

“Will’s letter?” he repeats. Is it fear that flickers in his eyes? Or is it something else?

“Yes. It told everything. That he and Nate were both prisoners of war, and both of them were sent to Camp Sumter.” My words spill before I can catch them back. “Something happened to Will there, didn’t it? He had no glorious death on the battlefield. He wasn’t any hero. That’s what Nate meant when he spoke about being the only one to slip the noose. Did Will commit some horrible crime while in prison? Was he…punished? Was Will hanged in prison?” I feel my lungs strain against the pressure of my corset as I voice my most shocking thought. “Quinn, was he?”

But he is shaking his head. “How did you get hold of that letter?”

“Nate gave it to me.”

“This changes everything,” Quinn says.

“It changes nothing,” I protest. “Except that you can stop protecting Will. Please, tell me the truth.”

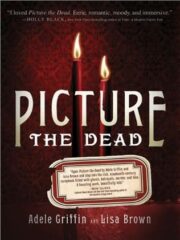

"Picture the Dead" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Picture the Dead". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Picture the Dead" друзьям в соцсетях.