Although Quinn doesn’t bring up my leaving Pritchett House, he has injected the fear into me. Where would I go? What would I do? Over the next few days, I am a mouse in search of a new flowerpot under which to hide.

Homing in on what she (rightly) perceives as my insecurity, Mrs. Sullivan starts to give me lists, misspelled commands on scraps of brown butcher paper, and though she hasn’t assigned me the charwoman’s work yet my hours are spent sweeping, mending, and so much dusting that my lungs ache from sneezes. But I do everything she asks, afraid to raise a fuss.

But by the week’s end, when Uncle mentions that he’ll be going into town for an early meeting at the bank, I’m resolute. This Saturday is my only chance, for it’s when Mrs. Sullivan takes a half day to commiserate with her elder sister, Millicent, over tea in Fort Hill. She flourishes a newly printed carte de visite that she’d ordered expressly for the occasion though it seems a bit of a pretension, considering Millie has been receiving her sister every other Saturday for the past thirty years.

But Mrs. Sullivan has a dozen and surely won’t miss one, so a I spirit it into the folds of my apron while she checks her hat in the mirror.

She hurries out, lugging her basket that is no doubt stocked with stolen wares from our pantry. But she doesn’t open the carriage door, however, without burdening me with yet another list, this one for items to pick up from Kirke & Sons.

Battleship clouds glower in the sky that morning. I stay downstairs to ensure I’ll catch Uncle as he departs. My photograph and letter are hidden in my pocket, and my excuse is writ firm in my head.

“Mrs. Sullivan needs me to go to Merchants Row. Might I ride with you, sir?”

“For dry goods?” Uncle looks befuddled. “Couldn’t she send someone else? Next Monday, perhaps?”

“No one can be spared,” I demur. “We are sorely understaffed.”

His cheeks bloom with embarrassment. “Such are our sacrifices in wartime.”

“Yes, Uncle.” But he’s annoyed. He is a slipshod manager and we both know it.

On the ride into the city, Uncle Henry pays me no mind, though his dossier seems to perplex him. Once, he looks up hard at me, as if trying to calculate my personal worth versus cost, and then it’s my turn to blush as I imagine him pondering my financial inconvenience to his family.

And I would go! I want to shout at him. If I had half an opportunity, I’d leave today!

“Jennie, I need one word with you about that medium,” he remarks as we enter the heart of South Side, lively with Saturday morning hackneys and omnibuses as well as a few street vendors setting up their fruits and flowers.

“Yes?” There’s a squeeze in my heart. Does he know my morning’s plans?

Uncle brings his pocket watch from his waistcoat and pays excessive attention to polishing its surface. “On further inquiry, it seems this chap Geist is a two-bit fraud. As some of the fellows at the bank explained it, his camera is loaded with mirrors, double images. The specifics are beyond me, but it must not get out that we’d been hoodwinked.”

“Our visit was a private family meeting,” I jump in to assure him.

“Correct. For there’s no reason to doubt William isn’t in heaven with the Lord’s angels. I don’t need proof of it.” Uncle blinks rapidly. “S’pose I can see why Geist’s business might be a comfort to the uneducated. But we Pritchetts are made of sterner stuff.”

“Yes, Uncle. Without doubt.”

And that seems to settle it. Still, I worry that Uncle has just sent me a subtle warning against visiting Geist, and so after the carriage lets me off I pay my legitimate call at Kirke & Sons, where I put in an order for needles, rickrack, and a bolt of twill to be charged to our house account, all the while looking over my shoulder to see if Uncle has followed me.

A spy must watch for all options and exits. I can almost hear Toby whisper it, his words a secret spell in my ear.

“We’ll deliver by early next week. But your account is three months in arrears,” says old Mr. Kirke, looking down over his pincenez and handing me a sheaf of horrifyingly overdue bills. “You’ll need to settle in full.”

I nod, mortified, and resolve to hide the bills away as I take leave for Geist’s townhouse. How awful. Somebody needs to confer with Uncle Henry about the household debt, but it won’t be me. Aunt a seems to have lost any ability to manage Pritchett House. Awkward as it might be, perhaps I should speak to Quinn.

Geist opens the door himself, which catches me by surprise. And he has company, which I also didn’t expect. His guest resembles my girlish imaginings of Moses. His floss of long white hair is balanced by an equally snowy beard. That, the pouches under his eyes, and his shabby Inverness give him the look of a wandering holy man.

Geist introduces him as Mr. Locke, the war photographer. “He has just returned from a field tour. Thirteen states in six months,” says Geist, but Mr. Locke clearly isn’t inclined to speak of it. His lips press thinly, and he avoids Geist’s eyes as he murmurs in his rasping voice about the promise this year of an early spring and how he will be heading up to Portland come April. The strings and pulleys of his conversation yank our talk far from topics such as where he’s come from and what he’s witnessed.

Eventually Geist escorts Locke down the steps to a waiting coach.

“Poor man can’t even live under the same roof as his most recent work,” Geist says as he reenters, bolting the door and rubbing his hands against the cold. “He has given it to me to archive.” He gestures to a battered satchel by the stairs.

“May I see?”

“It’s nothing you’d want to look at.” The photographer grimaces. “Locke has been from Anderson to Shiloh. Most of this winter he followed General Sherman to Savannah, documenting the ruin. He thinks his images will act as living history so that we don’t repeat our mistakes.” There’s no mistaking the skepticism in Geist’s tone. Then he rolls back onto his heels, his fingers webbed across his chest. “So what can I do for you, Miss Lovell? For I presume there’s a purpose to your call?”

“Yes. You were correct, after all.” I give him my print and prepare myself for his astonishment.

He stares, lifts his brows. “Intriguing.” He hands it back. “Yet I find it curious that you’d want to dupe me.”

“Dupe?” I almost laugh. “You think I meddled with this image?”

“What else should I think?”

Bewildered, I look for what Geist sees. In new light the black curlicues of the iris petals look different. A delicate but all-toohuman work of quill and ink. “I swear on my life, sir. I didn’t touch it.” My finger crosses my heart, a gesture of childlike earnestness and yet I am feeling increasingly, mortifyingly childlike.

“And I swear on mine, neither did I. And so now we circle each other, wondering who is the charlatan?”

Truly, not the outcome I’d expected. “I don’t know what to say…” I falter. “Except that no matter what you think of this photograph, I’m here as a believer. On my last visit, you were convinced that Will’s spirit had come to me. I couldn’t bring myself to admit it at the time. I’d had a vision right in your parlor, of one afternoon during my last summer with Will, when a prankster had destroyed his sketchbooks by pitching them into the water. But then it was more than a memory. It was as if Will had conjured his very life energy to stand before me.”

Geist is listening. I take it as a sign to continue. And so I confess my choking nightmares and my belief that the black irises in the photograph linked me to my discovery of Private Dearborn, which couldn’t possibly be pure coincidence.

Finally, I take Will’s letter from my purse and hand it to him. Geist opens it and reads.

“You see, it’s my proof,” I tell him. “Will must have got himself a into some terrible trouble, before the end.” My fingers twist at the place where my engagement ring once sparkled. I’m as unused to its absence as I was to its weight. “Whatever Will has done, perhaps he wants to communicate something to me. I think he wants me to know that he is angry enraged about something. Just like that day by the lake. If your photo ”

“He mentions yellow jackets and mosquitoes,” Geist interrupts, lifting his eyes from the letter. “A pestilence of summer.”

It takes me a moment to understand. “But hardly ever found in spring,” I say slowly. “Will was killed May sixth.”

“He was reported killed. You saw the telegram?”

I nod, thinking of it in my book. “I did. Signed by a Captain Fleming.”

The spiritualist looks puzzled as he rocks back on his heels. “Undoubtedly, Fleming acted on the power of his best judgment.”

“What are you saying?”

“I am saying that a man cannot die twice, both in the spring and in the summer. Somewhere there is a falsehood. Most likely with Fleming’s record.”

“Well.” I am taken aback. An answer, but not the one I’d have wagered. “If there’s a cover-up, my cousin Quinn knows more than he’s telling.”

Geist frowns. “Perhaps you should let sleeping dogs lie.”

“Except that nobody is sleeping,” I say. “Nobody is at rest. That’s why I’m here. Mr. Geist, you said on my last visit that if you took my photograph it might help me commune with Will. And so I thought if we could take the photograph today, I’d have another chance ”

But he is tut-tutting me. “Your visit is ill timed, Miss Lovell. The photogenic process is a recipe of art and science. There’s not enough light today. Exposure would be interminable.”

Geist must see my disappointment. “Stay for tea,” he says. “Though it’s not a perfect day for a photographic portrait, I have several sheets of albumen paper drying in my darkroom. Perhaps in an hour or so the clouds will have broken up. And then,” he says, with another dubious glance at Will’s letter before he folds it and returns it to my hand, “we shall see what we shall see.”

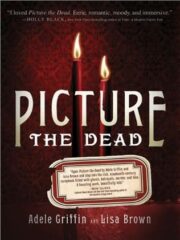

"Picture the Dead" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Picture the Dead". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Picture the Dead" друзьям в соцсетях.