With Uncle Henry away, Aunt takes supper in her room. I eat with the servants in the kitchen. The table is full. Uncle has hired on some men to help patch a leak in the roof. Raucous and friendly, they all leave afterward for the village and a few more pints and laughs at The Black Eye.

“Don’t you ever wish you were a man?” I ask Mavis later, as I’m having my bath in the scullery with Mavis on lookout. It’s our new custom, since it doesn’t seem fair to ask Mavis or any of Mrs. Sullivan’s overworked day girls to haul the washtub plus endless buckets of boiled water up the three floors. Besides, the scullery is almost cozy, near as it is to the overheated kitchen.

“Not the fighting part, but for the fun of it,” Mavis answers. “Mostly I’d like to roam free and never have to scour pots or have babies or wonder where my husband’s catting off to nights. Now, get scrubbing, Miss. Though by the look of your neck ’n’ nails, by the time I go in the water’ll be gray.”

On my way to bed, I check in on Quinn dozing in his armchair by the fire, and I accept his unprecedented invitation to join him for a hand of euchre. The game leaves him animated.

“Let’s play another round. For stakes,” he says as his fingers expertly shuffle the deck.

“If I had any.”

“Poor Fleur!” He smiles.

I smile to hear my old nickname, bestowed by my cousins from my long-ago summertime habit of arranging wildflowers in my hair. Funny, the things Quinn remembers. Of course his mind is as sharp as a nail even now. I curl myself more comfortably in my chair as he deals the deck.

“You seem more at ease these days.”

“Perhaps because I have more to see,” he says, referring to the fact that against the doctor’s orders, he has removed his eye patch. Quinn has a notion that his skin must be exposed to air to heal. I don’t tell him how I wish he’d kept it covered, how unnerved I am by his damaged eye that moves back and forth like a trapped fly behind his puffed, blue skin.

“Or perhaps I’m only grateful that after a month home,” I continue carefully, “you are paying me any attention at all.”

“Not fair, Fleur. We’ve always been close.”

I shrug. Close is not a word I’d have used. Though I suppose he has been closer to me than to anyone else since his return. Before the war Quinn was endlessly pursued by the smart young Brookline and Boston set, but he’s been home for weeks, and has refused to see any friends. Partly I’m sure it’s got to do with his injury, which makes him self-conscious.

“Let me lend you some money for cards,” he suggests, a smile playing on his lips, “and you can pay me back later.”

“Ha! You have a more optimistic view of my fortunes than I.”

Quinn laughs outright, which catches at my heart, he sounds so much like Will. He enjoys cards, and I play longer than I want until the clock in the hall strikes twelve long chords. As I leave, I give Quinn’s unshaven cheek a quick peck and abscond with the jack of hearts. It’s my first kiss for anyone since Will left, and I’m surprised by the spark of feeling it ignites though of what specific emotion, I’m not sure I could say. My lips feel as if they’ve brushed fire, and my heart trips in my ribs. Does Quinn notice? I avert my head as I hasten to the door.

“Jennie.” At my name I stop. “A question.”

I pause and turn.

“Did you really love my brother?” Quinn asks. “Or did you just love him back?”

I can’t hide that I’m startled. “What do you mean?”

Casually, he says, “The oldest son. The heir of Pritchett House. You would have been put in a sticky position if you’d rejected his advances. You know how…persuasive Will could get.”

“I wasn’t forced to love Will.” A nervous laugh catches and dies in my throat.

“No. Not overtly.” Quinn looks uncomfortable. “Ah, I’m being an ass. When all I wanted to comment on was your sweetness, Jennie. You give so freely of your time and good humor, I wondered if Will and I ever realized how much we depended on it.”

Then he selects a book from a stack on the carpet and opens it, pretending to be absorbed, and clearly embarrassed by his confession.

Quinn’s newfound sensitivity is touching. I’m happy that he has spoken his brother’s name, even if the question he posed was odd. I had never conceived of rejecting Will, but I assumed it was because I loved him, not because I feared any consequence. But the hour has grown late for such prickly introspections.

Though I’d set a fire before dinner, it has died and the room is cold. The glass is frosted over, and my candle is a single star in a dark sky. I pull out my scrapbook and page through notes from Toby, uneven and misspelled; letters from Will, with his elegant script and stilted declarations of love; still more scraps of paper, oddities, and curios, before I reach the pages I have kept from Will’s sketchbook. Where I find him again. His best gift was for capturing the outdoors.

A thread of black ink becomes a bird wing or loop of ivy. I linger over them before turning to a section in the back with drawings, some of myself, where I compare Will’s art with Geist’s print.

Will’s pen unlocks my secret moments. My smile on the cusp of laughter. The breeze in my unbound hair. The bow of my neck against the sun. Fleur. I’d forgotten. It’s a name that conjures summers past when I gathered starflowers, bluebonnets, thistle, and daisies on the riverbanks, twining them into bracelets and crowns, filling vase after vase, setting them on every windowsill and mantel, much to Aunt’s dismay.

But in Geist’s print I glower. As if my closed mouth might hide a pair of fangs. We are all dour, all but Viviette, who looks positively beatific.

And then I see what has eluded me. This fragment of detail is now so clear, and yet so radically different, that for a moment I wonder if I’ve lost my mind.

Quickly, I pry the paper from its backing and bring the candle close. And yet I’m sure my memory is serving me correctly and that the discrepancy is real. Unlike the Harding photograph or the print that I’d set on Uncle Henry’s desk, in this image Viviette’s head is crowned not by holly berries but by a wreath of dark flowers.

But. The negative could not have changed.

Irises. I trace them with my fingertip. They are inky flames leaping around the angel’s head. Transfixed, I can feel myself slipping away again. Geist had called it the undertow, and that strange word now redefines itself as I skid deep into memory.

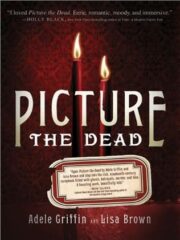

"Picture the Dead" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Picture the Dead". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Picture the Dead" друзьям в соцсетях.