“I’m a doctor and these are my patients. I won’t leave!” The soldiers ignored him and began searching the belongings of the patients. “What are you doing?”

“Searching for contraband,” said what appeared to be the leader of the band as he fingered a pocketknife. He put the object into his pocket and picked up a book.

One of his fellows laughed. “‘Contraband!’ Oh, good one, Pyke!”

“Since when is a man’s Bible contraband?” Bingley cried. He moved to confront the man Pyke. “Put that back!”

Suddenly, Pyke drew a knife. “Resistin’ the surrender, mister?” he growled dangerously. “You don’t want ta be doin’ that—no, sir.”

During the whole time, Darcy had lain quietly, pretending to be asleep, all the while slowly reaching beneath his cot. As Pyke gestured at Bingley with his knife to the enjoyment of his fellows, Darcy whipped out his saber and threw himself at their tormenters. Sweeping backhanded, he struck one on the head with the pommel, stunning the man, before grasping Pyke with his left arm about his throat, threatening him with the sword and using him as a shield against the last soldier.

Darcy stared at the third man with a cold, deadly look. “You will not threaten the doctor while I live.”

“Don’t do anything!” cried Pyke. “He’ll kill me!”

“No, he won’t,” came a voice from the entrance to the ward. “Drop that sword, Johnny Reb.” Darcy turned, forcing Pyke between him and the new threat. He saw a dark-haired man in a blue captain’s uniform holding a pistol on him from his left hand.

“I am Captain Darcy,” Darcy said in his best command voice. “Are you in charge of this rabble?”

“I am, Captain. My name is Whitehead. Release that man, or I shall be forced to shoot you.”

“Your men, Captain, were stealing from sick and wounded men and were about to attack a doctor. This is strictly against the rules of war. Tell them to stand down.”

Captain Whitehead’s mouth twisted into an amused grin under his pencil-thin moustache. “Were they? Very well.” Whitehead barked out an order and the two Yankee soldiers backed away, holstering their pistols. “Good enough, Captain?”

Darcy hesitated a moment, then slowly withdrew his strong left arm from Pyke’s throat. Pushing the frightened corporal away, Darcy reversed his sword and offered the pommel to Whitehead. “My sword, sir. I am yours to command.”

Whitehead holstered his pistol and took the weapon. “A fine saber, Captain. Where on earth did you get it?”

“It’s Spanish, sir—fine Toledo steel. It’s been in my family for four generations.”

“Hmm.” Whitehead inspected the workmanship with ill-disguised envy. “You would hate to lose it, I am sure. Well, have no fears, Captain.” Whitehead glanced at his men standing behind Darcy and nodded. Bingley saw the men move to his friend and cried a warning, but it was too late. A moment later, Darcy lay sprawled insensible on the cave floor. Bingley tried to help, but a soldier seized him, pinning his arms behind his back.

Whitehead walked over to the prone man and laughed. “Yes, Captain, I would not concern yourself over your sword. You’ll have no need for it where you’re going.” He turned to his remaining men. “Take this man prisoner—hold!” As the two lifted Darcy from the ground, Whitehead rifled through the unconscious man’s pockets.

“You bastard!” cried Bingley as he struggled in the soldier’s grip. “You’re no better than a common thief!”

“Now, now, Doctor,” Whitehead remarked as he withdrew Darcy’s pocket watch, “there’s nothing common about me at all. Besides,” he turned to Bingley, “you’re a Rebel and a traitor. You’re fortunate that I don’t shoot you out of hand where you stand.”

“You won’t get away with this,” Bingley vowed.

“Oh, I think I will. You are nothing. I’d keep quiet if you value your parole.”

Bingley threw a rather strong curse at Whitehead, and the officer lost all good humor.

“Very well, Doctor. Take him away, boys.”

July 5

Major General Ulysses S. Grant, commander of the victorious Army of the Tennessee, sighed as he enjoyed an after-supper cigar and whiskey in his tent with his friend and subordinate, William Tecumseh Sherman, Major General of Volunteers and commander of his XV Corps.

Sherman puffed his cigar. “I told you, Grant, that if you stayed in the army, some happy accident might restore you to favor and your true place. Well, when news of this victory reaches Washington, you’ll be the toast of the nation.”

“Perhaps, perhaps. You did give me good counsel, though.”

“Hah!” Sherman gulped down a bit of his drink. “You stood by me when they all thought I was crazy before Shiloh, and I stood by you when they all said you were a drunkard!”

Grant eyed him. “I was not a drunkard.”

Before Sherman could respond to that, an aide came in with a message for Grant. The weary-looking bearded man scanned the two-page dispatch while Sherman refilled his glass. He looked up as a curse escaped Grant’s lips. “Trouble?”

The general tossed the notes upon his field desk. “Yes! Some fool is demanding that a Rebel doctor and one of his patients be arrested for insubordination, assault, and violation of the surrender.”

“So?”

“Well, there is also an affidavit from the doctor stating that Union soldiers were stealing from the patients, and he demands I take action against them!”

Sherman sat back. “It happens, no matter how many orders we issue or men we arrest. If it gets too bad, we put a few in the stockade. Is there something else?”

“The officer involved is a George Whitehead, attached to XIII Corps. Made captain because his father is the postmaster back in Illinois and active in the Republican Party. I’ve had complaints before about this fellow, but McClemand always stood by him.”

“You think Whitehead is guilty?”

“I’ve no reason to trust the man.”

Sherman grunted. Both the Union and Confederate armies were filled with political officers—men who received their rank not because of military training or experience in battle but because of their civilian connections. They were usually incompetent troublemakers for their professional brethren, but they had friends in high places, and it was detrimental to one’s career to oppose these men without being very careful. The former XIII Corps commander, Major General John A. McClemand, had been just such a man, and it had taken Grant months to orchestrate his removal.

Grant pinched the bridge of his nose with two fingers. “I finally got rid of McClemand, and now I must divest myself of another political officer. Damnation! I’ve a war to fight!”

“That was good work, shipping out that vainglorious fool,” Sherman said as he took a sip of his whiskey. “Why not do the same with this bastard? Kill two birds with one stone.”

“Eh? What’s that?”

“Whitehead. Have him escort his precious prisoners to prison camp with a letter requesting transfer. Let him be someone else’s problem. Meanwhile, you don’t have to try both Whitehead and those Rebels.”

Grant sat back. “Sherman, I knew there was a reason I let you drink my whiskey.”

Jackson, Mississippi—1865

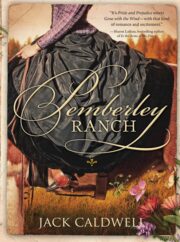

"Pemberley Ranch" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Pemberley Ranch". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Pemberley Ranch" друзьям в соцсетях.