“Too long, Bertram. I’ve been away too long.” Darcy took a sip as Bertram raised an eyebrow. “I want you to tell me everything that’s been going on around town.”

“Everything? That’s going to take some time.”

“I have the time, if you do.”

“Then I’d better tell Rushworth to put on another pot. We’ll be here awhile.”

Chapter 11

August

The new month saw the end of Jane’s confinement, and Beth and Caroline were able to put aside their mutual loathing long enough to help Mrs. Bennet and Charles bring Susan Jane Bingley into the world. Beth thought the little girl was the prettiest thing she had ever seen. Caroline’s only comment was, “Susan—Susanna—was my mother’s name. That’ll do.” Beth wasn’t sure if she saw a gleam in Caroline’s eye, so swiftly did the other woman excuse herself to rest.

Jane recovered quickly from her ordeal, so only two weeks later, Charles helped his sister to board the stagecoach back to Louisiana. Caroline made one last attempt to convince Charles to move to New Orleans before taking her leave of Jane. The party waved as the stage left town, Beth feeling guilty relief that the woman was out of Jane’s life.

Beth, too, found her help was no longer needed and returned the next day to the farm. She was content to fall back into the routine of chores and was happy in the familiarity of her family. She was pleased to see that Kathy continued to mature and take more responsibility around the house, but Lily was still Lily—young and lazy.

The only other change was with her father; he seemed to spend more time than usual closed up in his study. When he was with the family, mostly at table, his face carried lines never seen before. There was a slight air of worry about the man, but when Beth asked him about it, he dismissed her concerns with a smile.

Mrs. Bennet mentioned something about the harvest not being what it should, but she was confident that, if this year was tight, next year should be better. Other than that, she appeared to have changed little. Beth shook her head. For all her mother’s emotional outbursts, she was a farmer’s wife through and through. Fanny Bennet was a levelheaded, dependable sort of person, except when it came to her daughters’ futures. Knowing a good marriage was the difference between plenty and poverty, happiness and hunger, she worried incessantly over the lack of eligible men in Rosings. When it came to the farm, however, she was as stoic as her husband. It was a farmer’s lot to be held hostage by the whims of markets and weather. The phrase “Things will be better next year” sustained the Bennet clan through the worst of times in the past, and Beth knew it would serve as a source of steadiness for her family in the future.

A few days later, Beth, riding her beloved Turner, found herself at Thompson Crossing. The horse started to move forward, but Beth held him back. Normally she would not have hesitated to cross the ford and allow Turner free rein across the vastness of Pemberley, but after her argument with Darcy at the B&R, she had second thoughts.

Yes, Darcy had forgiven her—he made that clear in town— but Beth still felt uneasy. Her terrible accusations, mostly built on lies and willful miscomprehensions, were unworthy of clemency. Beth felt a need to punish herself for hurting such a man as Will Darcy.

Looking at the situation dispassionately, Beth could finally see that there was little to complain about when it came to the owner of Pemberley Ranch. He was kind to his kinfolk and respectful of others. True, he was a reserved person and hard for strangers to approach, but the man’s ironclad sense of justice and generous, forgiving nature more than made up for it.

Beth could now understand the incident in Zimmerman’s store months ago. Darcy had somehow expressed in a few words and a quiet look his displeasure at how poor Mrs. Washington had been treated. That was why Mr. Zimmerman rushed to the back door to see to the woman’s order. Beth had to shake her head. How many other rich men would wait in line behind anyone, especially a former slave?

Stupidly, Beth had not considered the enormous compliment Darcy had paid her by allowing an affectionate acquaintance to blossom between herself and his relations, particularly after Mary’s overheard outburst about Catholics. Beth knew in her heart she wouldn’t be so forgiving over such an insult to her faith. She was glad that Henry Tilney had set her family straight about the matter, but Beth hardly thought about the matter anymore. She shouldn’t have forgotten, she berated herself, because that belittled the gesture made by Will and Gaby, reaching their hands out in friendship.

Beth had ignored all that. She had allowed herself to hate someone without knowing who he was. George’s falsehoods found fertile ground to grow in Beth’s mind because she had spent years cultivating it. She, alone in her family, held on to anger over the war. She was the only one not to put it truly behind her.

She now knew the reason she wouldn’t let go of the war— she was afraid she would dishonor the memory of Samuel. Her initial anger at his death was understandable, but she had perpetuated her anguish by embellishing the facts. Samuel wasn’t killed by the Rebels; he died of influenza while in camp. An honest person would have to admit that it could have happened anywhere at any time. Didn’t a cholera epidemic sweep through Ohio in ’49, the year before she was born? Her parents told her the family was lucky to have been untouched by it.

Fair was fair, and Beth had not been fair to Will Darcy or the South. Truly, the person she had been angry with was, in fact, Samuel himself. She never wanted her brother to enlist in the first place, but, caught up in the patriotic fervor engulfing the community, Samuel couldn’t wait to don the blue of the Republic, march off to defend the Union, and put paid to those foolish Rebels. Beth felt abandoned as her beloved brother and playmate joined the army and left home. Her only consolation was that the war would be short. Surely those silly Southerners would come to their senses and beg for mercy at first sight of the mighty Union Army. Only after Bull Run and Shiloh did both sides realize they were in a struggle to the death.

For almost two years, Beth waited in fearful anticipation for news of her brother. Perversely, she held on tightly to his promise to return, a promise no man could be certain to keep. Providence would either take Samuel or return him. When the hated telegram came, Beth wanted to lash out at someone, but it couldn’t be Samuel, and it couldn’t be God. It could only be the Confederates.

By the time she reached Texas, she thought she put the war behind her. After all, she had made friends here. But her confrontations with Darcy and Caroline, and the explanations afterwards, made her reexamine her thinking.

What she found made her uncomfortable. She realized she had allowed herself to befriend Charlotte, Gaby, and Anne, not because of their innate goodness, but because it flattered her own vanity. Beth permitted herself to be friendly to Southerners to prove to the world that she was open-minded, tolerant, and forgiving. Though she enjoyed her friends’ company, did she really respect them? Did she ever listen to their views without a critical ear? Did she ever give credence to their opinions? Charlotte told her about Darcy, and Anne tried to apologize, but Beth had dismissed them. In her estimation, Beth knew she was superior to them, not because of wealth, position, or education, but by the simple accident of where she was born.

Northerners were better than Southerners; it had been her belief for most of her life. The word of a Northerner must be taken over that of a Southerner. That was why she listened to Whitehead. Darcy challenged her, so she dismissed him. She felt free to heap all of her pain, grief, and disappointment onto a fine man who had suffered and lost more than she had.

No, Beth told herself. She wasn’t better than Southerners. She certainly wasn’t better than the man on whom she had heaped all her pain and disappointment over Samuel’s death. William Darcy, rather than being a wicked representation of all that was wrong with Texas, was the best man she had ever known. Instead of being thankful for his friendship, grateful for his understanding and patience, and appreciative for his regard, she had been mean, thoughtless, and hypercritical.

Beth fought back her tears. What a fool I was! How cruel and judgmental I was. I, who prided myself on my ability to read character and congratulated myself on being kind to those less fortunate, have been nothing but mean and critical. I believed everything George said because his stories confirmed my prejudices. Had I been in love, I couldn’t have been more wretchedly blind.

Pride has been my weakness. George didn’t seduce my heart but my vanity. His stories allowed me to remain comfortably ignorant and allowed me to look down on my neighbors. Even Miss Bingley, for all her haughtiness, deserves more compassion from me than censure. How would I behave had her misfortunes fallen upon me?

And Will Darcy. Why am I so distressed over him? I couldn’t be falling in love with him—it’s impossible. Yet, when I think how I wronged him, my heart is filled with a terrible sorrow. I don’t know why, but the very idea that he’s alive and might think poorly of me is unbearable!

I know he said he’s forgiven me—in fact, he apologized for his own behavior—yet, I can hardly credit it. For him to be so kind to me after I cruelly abused him is astonishing. I’m blessed I have the chance of being his friend and the chance to change for the better.

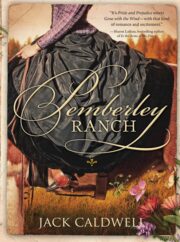

"Pemberley Ranch" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Pemberley Ranch". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Pemberley Ranch" друзьям в соцсетях.