With a shrug, she reached over to assist. They turned Darcy over, careful not to dislodge the towel, and unfastened the buttons. For the first time, Beth saw the bare chest of a man unrelated to her. And a fine, broad one it was. Unconsciously, she licked her lips.

Beth glanced up to see Anne grinning at her. “What?”

She laughed. “Nothing. Oh, we can’t get this off. We’ll have to turn him over again.” Once again on his stomach, the ladies were able to remove the shirt completely. They weren’t prepared for the sight before them. Beth gasped and Anne let out a sharp scream.

Bartholomew dashed into the room, arms filled with cloths and towels. “What is it? What is the matter—Oh, my God!” He stood stock-still at the foot of the bed.

Anne’s eyes filled with tears. “What happened to William? Who did this?”

Beth could not answer; her attention was fixed on Darcy’s back—a back completely covered in angry, white scars.

Chapter 10

July 5

When Beth came down for breakfast the next morning, she was not surprised to learn that Dr. Bingley had been sent for. She didn’t need to ask who Charles was there to see. Indeed, she was hard-pressed to get the man out of her head.

Anne glanced sheepishly at Beth, but with her mother in attendance, she refrained from speaking. It wasn’t until Mrs. Burroughs retired to her study to work on ranch matters that Anne moved to the seat next to Beth.

“Beth, about the dress, I’m so sorry. It was Will’s idea to surprise you—”

Beth cut her off. “Please, the less said about yesterday, the better.”

Anne, chastised, stared at her plate. “I hope you’re still my friend.”

Beth sighed. “I am. But friends don’t deceive each other.” Beth instantly regretted her words as Anne’s eyes filled with tears. But before she could console her, Charles came into the room.

“Well, he’ll live, but I can’t say he’ll enjoy it.” His jovial manner dissipated with one look at Anne’s unhappy face. “Forgive me, I shouldn’t be joking,” he said, misunderstanding Anne’s concern. “Will’ll be fine. He just needs a day o’ rest. He’ll be fit as a fiddle come tomorrow morning.”

Anne smiled her thanks to Dr. Bingley, and Beth realized she was relieved, too. Anne offered Charles some breakfast, and he sat down.

“Thank you, Miss Anne,” Charles said. “Beth? We’ll leave right afterwards, if you’re ready.”

Beth waited until Charles’s surrey was well out of earshot of the ranch house before she turned to her brother-in-law.

“Charles, I’ve recently learned some disturbing things about the war.”

“Is that so?” A puzzled Charles turned to her. “What brings this up?”

Beth had no answer but the truth. “Will Darcy and I were… talking yesterday, and it just came up.”

“Talking about the war? At a party?” Charles was flabbergasted.

Beth turned away to hide the flush on her face. “All right— we had an argument. He said George Whitehead ran one of the prisons you and Mr. Darcy were in. Is that true?”

“Yeah. Will doesn’t usually talk about those days.”

“Nobody does!” Beth cried. “It’s like it’s a great big secret!”

“Beth, war is a thing a man wants to forget.”

“Have you talked about it to Jane?”

Charles ignored the impertinence of her question. “A little. Where’s all this leading?”

“Last night, when Mr. Darcy got… himself injured, Miss Burroughs and I helped Mr. Bartholomew get him to his room. In the course of caring for him we… we saw his back.” Charles’s eyes grew wide. “Charles, where did those scars come from? Was Mr. Darcy whipped in prison?”

It took a moment for an astonished Dr. Bingley to say, “That’s not my story to tell.”

“Then he was. Charles, you can tell me. Mr. Darcy himself told us stories about horrible mistreatment in the camps, so you wouldn’t be telling me something I haven’t heard. He said George liked to have people whipped. Was it George who had Mr. Darcy whipped?”

Charles stared straight ahead. “Yes,” he admitted in a low voice.

“Why?”

“Because of me.”

“You?”

“Beth, this ain’t easy for me to talk about.” He took a breath. “Will and I were at Vicksburg, but instead of being paroled after the surrender like the others, we were arrested by Whitehead on false charges.”

“What were the charges?”

“Resistin’ the surrender, but that wasn’t the real reason. We knew too much. You see, we saw Whitehead and his men stealin’ from my patients. I complained, but instead of punishing Whitehead, his commanders placed him in charge of bringing us to prison.” Charles went on to talk of their trip to Camp Campbell in Missouri—how the transfer point-turned-prison was totally insufficient for the purpose intended, and how Captain Whitehead essentially became the commander of the place.

“The sanitary conditions were awful,” Charles continued. “The latrine wasn’t suitable for even a third of the men we had there. I was workin’ in the camp hospital—there was a shortage of Yankee doctors—so I went to the Yankee colonel to get permission to have a new latrine dug. The drunkard turned me down flat—said his engineers told him what we had would be more than adequate. Beth, he was wrong. That thing was dysentery waitin’ to happen.

“Food was always scarce, so Whitehead had the idea of us makin’ a vegetable garden for the guards. Each day, a team of men would be issued hoes and tools to work the ground. I saw my opportunity and went to Will with my idea. If the men spent an extra ten minutes a day at the end of their shift diggin’ a new latrine, we’d have it done in less than a week. Will told me to go ahead, as long as the guards knew what we were doin’. I didn’t have any trouble with them, ’cause I had pulled a tooth for the head of the detail, and he took a likin’ to me.

“Everything was goin’ along fine until, in an unexpected fit of sobriety, the colonel decided to hold an inspection. He took one look at the nearly-finished latrine and started yellin’, accusing us of diggin’ an escape tunnel. Guns were being pointed every which-way, so I stepped up and told him what it was. I was immediately taken in hand and dragged to a court of inquiry.

“There I was, standin’ afore the colonel with a nervous Whitehead at his side. Now, you see, it was ole George’s idea to have us prisoners make a garden an’ put tools in our hands, so he was ultimately responsible. I figure he was there to make sure I took the blame, not him. So Whitehead said nothing when his commanding officer accused me of organizing a mass escape, until the colonel started talking about havin’ me shot. I guess that was too much even for Whitehead—that, or else he was afraid of an investigation from higher authorities. That’s when he suggested that shootin’ a doctor would be bad for morale and flogging would be enough of a punishment.

“Just before sentence was read, there was a disruption at the tent entrance. I turned around to see Will walking in like he was a commanding general, surrounded by two guards. He was yelling that this hearing was illegal, a violation of the Articles of War. The colonel got mad, I can tell you, and demanded an explanation. Will said that they couldn’t punish a man following a lawful order, and that he, as commanding officer of the Confederate prisoners, had ordered me to build that latrine.

“I was shocked to see him, Beth, and not just because of his words, which was stretchin’ the truth a bit. That he was allowed anywhere near the tent was amazing. But I noted that one of his guards was the same sergeant whose tooth I pulled, so I guess he was repayin’ the favor by bringin’ Darcy to the hearing so that he could object.

“The colonel was spittin’ mad—screaming that he ought to shoot us both. Whitehead put a hand on his shoulder to quiet him down. He said, ‘Colonel, the captain is correct—we can’t punish a man for following a legal order.’ He then turned to Will, and Beth, I swear the man actually smiled as he said, ‘But we can punish an officer who encouraged insurrection against the lawful authority. Since Captain Darcy issued the order, let him be punished.’”

Beth’s hands flew to her mouth. “Oh, Charles!”

“Beth, I tried to stop it—I objected at the top o’ my lungs—but Darcy rode me down. Ordered me to be silent and obey. Whitehead had the guards take Will out immediately and execute the sentence.” He passed a hand over his face. “I wasn’t at the flogging, but since they didn’t revoke my hospital privileges, I was there when they brought him in afterwards. I’ll never forget that sight for as long as I live. They almost beat him to death—I feared for his life for nearly a week.”

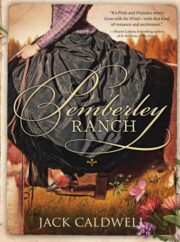

"Pemberley Ranch" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Pemberley Ranch". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Pemberley Ranch" друзьям в соцсетях.