Beth was shocked. “Three hundred men died? But… but the papers all said that Confederate prisoners were treated well.” She looked at Anne, who also sat with an astonished look on her face.

“You… you never told us, Will,” was all she said.

“It ain’t somethin’ a man likes to remember, Annie. God help me, I wish I could forget.”

“What happened?” Beth asked.

“Three things—mismanagement, malnourishment, an’ mistreatment. Ha, didn’t think I could get all that out.” Darcy looked perversely proud of his alliteration. “Camp Campbell wasn’t supposed to be a prison—it was a way station. But the real prisons weren’t ready. So there we stayed, as more an’ more men came. A thousand souls on a few acres. Sickness an’ starvation took more of the victims.”

“Starvation?” Beth cried. “But what of the food the War Department sent?”

“Oh, it came, what little they actually sent. We were right by the railroad siding, an’ we saw the Yankee soldiers unloadin’ the freight cars. Funny thing, though—not all of it got into the kitchens. Charles was workin’ in the camp hospital at the time, an’ he made friends with some o’ the guards. He found out from them that a lot of the food for the prisoners was sold to the townspeople.”

“By who?”

Darcy gave her a look. “Who do you think?” Darcy took another drink as Beth digested the implication. “We couldn’t complain about it without bein’ labeled malcontents and bein’ charged with insurrection. But we complained anyway, for all the good it did. George liked that word—insurrection. Most of us were accused of it at least once. He also liked the whip.” An unreadable expression came over Darcy before he turned to the fireplace. “Flogging was a weekly occurrence.”

Beth was having a hard time handling what she was hearing. How could a handsome and charming man like George Whitehead be the ruthless and dishonest monster Darcy was describing? It couldn’t be true, could it?

Darcy continued in an unemotional voice. “By the time they shipped us out, there were three hundred graves in the Confederate cemetery. Some o’ the townspeople didn’t want individual headstones—said it was ugly an’ we didn’t deserve it anyway—but decency won out. An’ as for Captain George Whitehead, he got a promotion to major.

“Camp Douglas[4] in Chicago wasn’t any better. We were crammed in with twelve thousand others in a place designed for half that many. Eighty acres o’ hell. They wouldn’t let Charles serve in the hospital. We never knew how many died—four to six thousand, Charles thinks, most in unmarked graves or tossed into Lake Michigan. An’ unlike Andersonville, nobody was punished for it.”

Darcy bowed his head before turning back to the ladies, both shaken by what they had heard. “All that kept me alive was wantin’ to get back home and see my daddy an’ my sister again. In the summer of ’65, I finally got back to Rosings, only to find my daddy sick. You remember, don’t you, Annie? I had to take over runnin’ Pemberley. For two years, Daddy and me ran the ranch together, me from a horse an’ him from his sickbed. By then, th’ Yankee carpetbaggers were movin’ in, but we paid them no mind. There was a ranch to run.

“Fitz an’ I took a herd up to Kansas in ’68. By the time I got back, Daddy had been in his grave for three weeks. And sittin’ on the front porch o’ Pemberley, pretty as you please, was good ole George Whitehead, late of Illinois an’ newly appointed Recorder of Deeds for Long Branch County, and Judge Alton Phillips, who had kept his job by kissin’ the asses o’ the occupation government in Austin. Whitehead was tryin’ to get himself named executor of my daddy’s estate an’ he was payin’ court to my grievin’ sister, while she was still wearin’ her mournin’ clothes.”

Beth’s jaw dropped. “Paying court to Gaby? But… but she’s not of age now!”

Darcy’s face screwed up in fury. “That’s right—and she wasn’t yet fifteen years old at the time.”

Beth thought she was going to be sick.

“Only reason I didn’t shoot that bastard and his scalawag friend right then an’ there was that Fitz stopped me. Convinced me that bein’ hung for killin’ those two would not help Gaby at all. But I told them—told them both—that if I ever saw either of them on Pemberley land again, I’d kill them.

“I told Cate what had happened, an’ you know what she said? Told me to forget it. That times had changed, an’ we had to change with them. There was a new game in Austin, an’ if we were going to get ahead, we’d have to play along.” He drank down the last of his brandy.

“So, I’m sure you can understand why I don’t give a good goddamn what happens in Rosings, Miss Bennet. I went to war to serve my town an’ my state—defend my new country—an’ when I came back an’ needed help, where were the good people of Rosings? I ask you—where were they? Hidin’ under their beds! The hell with ’em!” He staggered back over to the sideboard for a refill.

Beth turned to Anne. “Is it true?”

Anne nodded. “We all heard about it. We were afraid Whitehead was going to call in the army and occupy the town. We were all scared for the longest time. But when nothing happened and Whitehead started charming everybody, the town… forgot.”

Darcy turned from the sideboard and raised his refilled glass to the ladies. “And so I hope I’ve been exonerated of bad behavior towards the Honorable George Whitehead. Here’s to you, you son-of-a-bitch.” Darcy tossed down half the glass. “And you’re now free to hate me, Miss Beth, on my own merits and not on other people’s opinions.”

“I… I…” Beth composed herself. “I really don’t know what to think right now, Mr. Darcy.”

Darcy just stared at her. “I’m sorry about your brother. I lost a lot of friends in that damned war, but I didn’t lose a brother. I’m really sorry for your loss.”

Beth bowed her head. “Thank you.”

“You gotta understand war,” Darcy went on. “When you’re on th’ battlefield, nothin’ matters except survivin’ and watchin’ out for your fellows. The other side, well, it’s like they’re not people, you see. They’re not human. You’ve got to kill them, ’cause they’re tryin’ to kill you. If a man stops to think about what he’s doing, about what war really is, you… you just can’t do it. You hesitate. An’ if you hesitate, you die, or the man next to you dies. You can’t allow yourself to think.”

Darcy took another drink. “If your brother was here today, I’d shake his hand an’ call him friend, ’cause he would know what I’m talking about. Just like that Buford fella I met today. Country, cause, flag—it don’t mean anything when th’ shootin’ starts. Only keepin’ alive. He’d know; he’d understand. I’m sorry, Beth. I’d give anything if he could be here today. Anything.” To Beth’s dismay, tears freely ran down Darcy’s proud face. “I’d trade places with him, if it would make you happy—”

Just then, Darcy lost his footing and, with a crash, fell to the floor. The two ladies jumped up and ran to his side to find the young rancher insensible on the floor, blood seeping from one side of his scalp. Beth was alarmed and stood to get help when they were joined by a white-haired man in a black jacket.

“Bartholomew!” cried Anne. “Where did you come from?”

“I was just outside the door, miss,” the butler said as he examined Darcy.

“Were you there the whole time?” Beth asked.

His eyes flicked over to her. “For much of it. It’s my job to look after you, Miss Anne,” he explained.

“Are you following me?” Anne demanded angrily.

“Of course not,” he said smoothly. “I just happen to be in your general vicinity as often as possible.” He glanced at her. “Mrs. Burroughs knows nothing of this.”

Anne stared at him, confused.

“I think Mr. Darcy struck his head as he fell,” the butler determined. “The damage is less than it seems. Head wounds do bleed freely. He needs to rest. I don’t envy his head when he wakes in the morning.” He slid his hands under Darcy’s arms and tried to lift him. Beth immediately moved to help.

“Miss Bennet, please! It is unseemly!” Bartholomew complained.

“Mr. Bartholomew, it’s obvious you need assistance, and I am no helpless female. I will help you get Mr. Darcy upstairs.” Beth’s words inspired Anne to do the same, and despite the butler’s protests, they worked together to maneuver the barely conscious man up the stairs and into a guest bedroom just across the hall from Beth. They were fortunate that Darcy could still make his legs work, for he was too tall and heavy even for the three of them. A towel was placed against his head to stem the bleeding before they allowed him to fall upon the bed.

“That won’t last,” Bartholomew said as he observed the towel turning red with blood. “I will fetch new cloths straight away.” With that he left the room.

Beth stared at the man sprawled across the bed, trying to come to terms with her feelings. She was mortified to learn that most of what she held against him was based on her own ingrained prejudgment and other people’s lies. Just who was William Darcy?

“I’d give anything if he could be here today,” Darcy had said. “Anything. I’d trade places with him, if it would make you happy.”

Will Darcy would die for me?

Anne moved over to Darcy’s towel-covered head. “Beth, help me.”

“What? What are you doing?”

“If we don’t get his shirt off, he’ll get blood on it.”

Beth hesitated a moment, frozen by the impropriety of the suggestion, before her innate sense of the absurd promoted itself. Beth Bennet, you’re already in a gentleman’s bedroom after spending a half-hour talking to him late at night in your nightgown. It can hardly get any more improper than it already is. At least Anne is here with me.

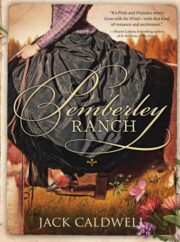

"Pemberley Ranch" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Pemberley Ranch". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Pemberley Ranch" друзьям в соцсетях.