“Yes, we are.”

Caroline’s nose seemed to rise. “That explains things. You have a lot to learn, Miss Beth, bless your heart.”

It didn’t take long for Beth to realize that Caroline used “bless your heart” as a means of taking the sting out of her most pointed insults.

Passing a ranch hand on the street: “He probably hasn’t had a bath this year, bless his heart.”

After meeting Charlotte: “Not every girl can be born pretty, bless her heart.”

Beth’s clothing: “I suppose livin’ on a farm you have to make your own dresses, bless your heart.”

When Caroline wasn’t holding court over the shortcomings in Rosings, she reflected on life at Netherfield, where the Bingleys grew up, or waxed elegant over New Orleans, where she was currently living with her sister and brother-in-law, the Hursts. The music, the food, the society—everything was superior in the Queen City of the South. She talked endlessly of the fine parties and balls she had attended, particularly about an event called “Mardi Gras.”

“A bal masque,” she explained, “only attended by the cream of society. Oh, Charles, if only you lived in New Orleans! With Mr. Hurst’s connections, I’m sure that you and dear Jane would soon be in the highest circles.” She then turned to Beth. “And I’m sure we could do something for you, too, dear.”

The only resident of Rosings who seemed worthy of Caroline’s notice was Will Darcy. He brought his sister to dinner one night, and Beth was amused at how Caroline practically threw herself at the man. It was obvious that the woman’s interest was purely monetary, for she spent the entirety of the dinner asking Darcy about Pemberley Ranch, ignoring Gaby altogether. Beth swore she could see dollar signs in Caroline’s eyes.

For his part, Darcy treated the woman with the same disdain he held for everyone. Beth almost laughed when the rancher grew so desperate for other conversation that he actually tried to talk to her. Beth’s eyes danced in mischief each time she spoke with Darcy, knowing that her actions would infuriate Caroline. Beth knew that if looks could kill, she would be dead. It never occurred to her to pay attention to Darcy’s expression.

At least the two women could share a room without incident. There were two beds—fortunately—and as Beth tended to retire and rise early and Caroline was of the opposite inclination, one was always asleep when the other was not.

Beth could not talk of Caroline’s behavior to either Charles or Jane. Beth did not want to trouble her tenderhearted sister in her delicate condition. And Charles was oblivious. “Oh, that’s just Caroline,” he would say. “It’s just her way. She’s had a hard time. You shouldn’t take it to heart.” The man was useless.

Charlotte was her only confidante, and Beth told her the story of her strained relationship with Caroline on the way home from church that Sunday.

“Beth, I’m so sorry. I had no idea that a sister of Doc Bingley could be so unpleasant.”

“It is a surprise. I keep waiting for Charles to say something to her, but he never does. He keeps saying she’s had a hard life and I have to forgive her. I don’t know how much more I can take.”

“How does she treat Jane?”

Beth thought. “Well, she’s never really mean to her. Caroline’s got plenty to say against everybody else in town, including my family, but it’s like she exempts Jane from criticism because she’s Charles’s wife. But she’s lazy and demanding and no help at all!”

Charlotte grinned and slipped into a Southern drawl. “‘We Southern belles are so delicate, we get the vapors if we do anything more than breathe, I declare.’”

Beth laughed. “She has her nose so high in the air she needs a guide to help her walk down the street, bless her heart!”

The girls laughed all the way home.

George Whitehead followed Pyke down the upstairs hall of Younge’s Saloon, towards room number five. He had received a letter earlier in the day from a Mr. Carson requesting a private business meeting. The pair paused before the door.

“You searched this fellow?” Whitehead asked Pyke. His henchman assured him that Carson’s person and luggage had been inspected and no weapons had been found. Whitehead touched his own gun belt and indicated that Pyke should knock on the door.

“Come in,” called a male voice.

“Stay close by,” Whitehead told Pyke as he turned the knob. Pyke nodded and stepped away to the head of the stairs.

Whitehead slowly walked into the bedroom. The room was bare—only a bed and dresser joined a small table with a couple of chairs. Whitehead’s quick glance took in a battered suitcase at the foot of the bed and a hat on one of the series of hooks on the wall opposite—but no inhabitant.

As alarm bells went off in Whitehead’s head, a voice softly said, “Close the door quiet like, or I’ll plug you right now.”

Moving slowly and deliberately, Whitehead stepped far enough in to close the door. Hands outstretched away from his body, he turned back towards the door. Standing beside it, in a spot where he could be hidden from the outside, was a man holding a pistol.

“If you’re holding me up, you’re bound for disappointment,” Whitehead said with a trace of bravado. “My wallet’s in my office.”

“Shut up. Move over to the other side of the room. Don’t talk.”

Whitehead became nervous. The man’s voice was deadly calm, indicating this was a planned ambush. He handled the gun with practiced ease. Whitehead knew he had to be very careful, or he would not leave this room alive. Hands up, he did as he was bid, placing the table between himself and the man called Carson.

“All right, now unfasten that gun belt—one hand only.”

Whitehead’s eyes never left his assailant as he slowly unbuckled the belt with his right hand. The holstered gun slipped to the carpeted floor. Whitehead stared hard at the man opposite. There was something familiar about him.

“I suppose you have a reason for all this, Mr. Carson—if that’s your real name.”

“Oh, I have a reason, all right. You’re George Whitehead, right?”

“I am.”

“The name Churchill mean anything to you?”

Whitehead’s blood ran cold—a ghost from his past had come visiting. He knew that yelling for Pyke would do no good. By the time Pyke could open that door, Whitehead would be dead.

“Yes,” Whitehead said. “James Churchill and I served in the war together.”

“I know. He told me all about it. I’m his brother, Frank.”

Whitehead said nothing, his mind racing.

“Where’s the money, Whitehead?”

Whitehead’s first thought was to deny everything, an impulse he dismissed immediately. Lying would do no good. He had to stall, though—he had to find out how much James had told Frank.

“Here.”

“I’ve come to get Jimmy’s share.”

“It’s not that easy.”

Churchill raised his gun. “This says it’s easy. Half of twenty-five thousand—that’s twelve thousand five hundred. I want it.”

“And then you’ll kill me?”

“Get me the money, and we’ll see. Don’t and you’re dead.”

“No, you’ll shoot me as soon as you get the cash. And I don’t blame you.”

Churchill gritted his teeth. “You killed my brother.”

“No, I didn’t. He saved my life.”

“Don’t you lie! You killed Jimmy and took all the money! The law came to the house during the war saying Jimmy took that money an’ was hiding out. But I knew that was a lie! Jimmy would never just leave and not get word back to his family. When months went by, we knew he was dead.” A feral look came into his eyes. “I knew what really happened, because Jimmy wrote to me—told me what you two had planned. Stealin’ a U.S. Army payroll. So I knew it was you that did away with him.”

Whitehead shook his head sadly. “That’s not what happened. Things didn’t work out like we thought. There was an extra guard, and he got the drop on me.” Whitehead grunted. “A bit like you did tonight. I thought it was all over for me when Jimmy jumped the man. Before I could pull my gun out, there were a couple of shots, and they were both dead. There was nothing I could do. I got the strongbox and Jimmy out of there and hightailed it.”

“I knew it. I knew Jimmy was dead. What did you do with him?”

“Buried him.”

“Where?”

“I really can’t tell you—in a farmer’s field, but it was in the middle of the night. Doubt I could find it again. I hid the money in my footlocker—right in plain sight.” Whitehead looked at Churchill. “Look, Jimmy didn’t tell me about you—all he talked about was his sister.”

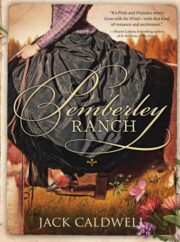

"Pemberley Ranch" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Pemberley Ranch". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Pemberley Ranch" друзьям в соцсетях.