"What a challenge it's going to be to mix paints to duplicate this color," she said, looking out over the water. "How are you?"

"Fine and eager," I said, and we began. Once we got started, we both lost ourselves for a while in our work, the process itself absorbing us, seizing our minds. Often, would imagine myself to be one of the animals I painted in my settings, seeing the world from the eyes of a tern or a pelican, or even an alligator.

We both had our concentration broken by the sound of hammering and looked at the boathouse to see Buck Dardar pounding on a lawn-mower blade. He paused as if he could feel our gazes and looked our way for a moment before starting again.

Miss Stevens laughed. "For a while there I forgot where I was."

"Me too."

"Want something cold to drink? I've got iced tea or apple juice."

"Iced tea will be fine," I replied. "Thanks."

She asked me how Gisselle was coping since Daddy's death and our return, and I described her behavior. She listened keenly and nodded thoughtfully.

"Let her alone for a while," she advised. "She needs to succeed at being independent. That will make her stronger, happier. I'm sure she knows you're there if and when she needs you," she added.

I felt better about it, and then we painted some more before stopping to enjoy the picnic lunch she had prepared. As we sat on the blanket and ate and talked, other students walked by, some waving, some gazing curiously. I saw many of my teachers and even spotted Mrs. Ironwood watching us for a few moments before crossing the campus.

"Louis was right about this lake," I said when we resumed our work. "It does have a magic to it. It seems to change its nature, its color, and even its shape as the day moves on."

"I love painting scenes with water in them. One of these days, I'm going to take a trip to the bayou. Maybe you'll come along as my swamp guide," she suggested.

"Oh, there's nothing I'd love better," I said. She smiled warmly at me, and I felt as if I did have a big sister. It turned out to be one of the best days I had had at Greenwood.

That night there was a pajama party at our dorm. Girls from the other dorms came over to listen to music, eat popcorn, and dance in the lounge. Afterward, they slept over, some sharing beds, some sleeping on blankets on the floors. During the night tricks were played. Some of the girls from the B quad downstairs went upstairs and knocked on a door. When the girls opened it, they threw pails of cold water over them and ran. Naturally, the girls upstairs had to respond. Somehow they had captured a couple of bullfrogs and cast them into the B quad lounge, sending the girls screaming through the corridors. Mrs. Penny was beside herself running from one section of the dorm to the other.

To my surprise, Gisselle found all this immature and stupid, and rather than participating and devising things for her little group to do, she retreated again to the confines of her room, locking the door behind her. I began to wonder if she wasn't falling into a deep depression and if that wasn't partly responsible for her fatigue every morning.

On Sunday I caught up on all my homework, studied for my English and math tests with Vicki, did my chores at dinner, and then dressed to go up to visit Louis. I told him not to bother Buck. I'd rather walk to the mansion. It was that nice a night, with a sky just blazing with stars, the Big and Small Dippers rarely as clearly delineated. I felt a pair of eyes on me as I walked and looked up and to my right to see an owl. I imagined that a human being walking alone at night through his domain was more of a curiosity to him than he was to me. It made me recall my life in the bayou and the feeling I used to have that animals there had grown accustomed to me.

The deer had no fear about drawing closer. Bullfrogs practically hopped over my feet; ducks and geese flew so low over my head, I felt the breeze from their wings stir the strands of my hair. I was part of the world in which I lived. Maybe the owl here sensed I was a kindred spirit. He didn't hoot; he didn't fly away. He just lifted his wings gently, as if in greeting, and remained like a statue on a branch, watching.

The large plantation house loomed ahead of me, lights burning brightly on the galeries, even though many of the windows were dark. As I drew closer, I could hear the melodious tones of Louis's piano. I rapped on the door with the large brass ball knocker and waited. A few moments later Otis appeared. He wore a troubled look when he set eyes on me, but he bowed and stepped back.

"Hello, Otis," I said cheerfully. His eyes shifted to the right to be sure Mrs. Clairborne wasn't watching from a doorway before he returned my greeting.

"Good evening, mademoiselle. Monsieur Louis is waiting for you in the music studio. Right this way," he said, and began to lead me through the long corridor quickly, but I looked to my left just in time to see a door closing and thought I caught a glimpse of Mrs. Clairborne. Otis brought me to the studio doorway before nodding and retreating. I entered and watched Louis play for a few moments before he realized I had arrived. He wore a dark blue velvet sports coat with a white silk shirt and a pair of blue slacks. With his hair neatly brushed, he looked handsome. When he turned toward the door, he stopped instantly and sprung from his stool. I immediately noticed something different about the way he looked in my direction and the confidence with which he now walked.

"Ruby!" He stepped quickly across the room to take my hand. "I can see you silhouetted clearly," he declared. "It's so exciting, even to view the world in grays and whites. It's so wonderful not to worry about bumping into anything. What's more, occasionally I get a flash of color." He reached up to touch my hair. "Maybe I'll see your beautiful hair before the evening comes to an end. I'll try. I'll think about it and I'll try. If I concentrate hard enough . . .

"Oh," he said, stepping back a bit, "here I am going on and on about myself and not even asking you how you are."

"I'm fine, Louis."

"You can't be fine," he insisted. "You've been through a terrible time, a terrible time. Come, sit on the settee and tell me everything, anything," he said, still holding my hand and leading me toward the sofa. I sat down and he sat beside me.

There was a new and brighter radiance in his face. It was as if with every particle of light that pierced the dark curtain that had fallen over his eyes, he came back to life, drew closer and closer to a world of hope and joy, returning to a place where he could smile and laugh, sing and talk and find it possible to love again.

"I don't mind your being selfish, Louis, and talking about your progress. I'd rather not talk about the tragedy and what I've just been through. It's still too fresh and painful."

"Of course," he said. "I only meant to be a sympathetic listener." He smiled. "Someone on whose shoulder you could cry. After all, I cried on yours, didn't I?"

"Thank you. It's nice of you to offer, especially in light of your own problems."

"We're better off not worrying about ourselves, and to do that, we have to worry about others," he said. "Oh, don't I sound like some wise old man. I'm sorry, but I've had a lot of time to sit and meditate these past few years. Anyway," he said, pausing to sit up straight, "I've decided to give in and go to the clinic in Switzerland next month. The doctors have promised me that I would stay there only a short time, but in the interim, I could attend the music conservatory and continue with my music."

"Oh Louis, how wonderful!"

"Now," he said, taking my hand into his and softening his voice, "I have asked my doctor why my eyes have suddenly come alive again and he assures me it's because I have found someone I could trust." He smiled. "My doctor is really more what you-would call a psychiatrist," he said quickly. "The way he describes my condition is that my mind dropped a black curtain over my eyes and kept it there all this time. He said I wouldn't let myself get better because I was afraid of seeing again. I felt safer locked in my own world of darkness, permitting my feelings to escape only through my fingers and into the piano keys.

"When I described you and the way I felt about you, he agreed with me that you have been a major part of the reason why I am regaining my sight. As long as I have you nearby . . . as long as I can depend on you to spend time with me . . ."

"Oh Louis, I can't bear to have so much responsibility." He turned red.

"I just knew you would say something like that. You're too sweet and unselfish. Don't you worry. The responsibility is all mine. Of course," he added, sotto voce, "my grandmother is not at all pleased with all this. She was so angry she wanted to employ another doctor. She had my cousin over here to speak to me to try to convince me I felt the way I felt because I am so vulnerable. But I told them . . . I told them how it was impossible for you to be the sort of girl they were describing: someone who connives and takes advantage.

"And then I told them . . ." He paused, his face becoming firm. "No, I didn't tell them—I demanded—that you be permitted to visit me whenever you can before I go off to the clinic. In fact, I made it very clear that I would not go if I didn't see you as often as I wanted, and . . . of course, as often as you wanted to see me.

"But you do want to see me, don't you?" he asked. His tone sounded more like a pleading.

"Louis, I don't mind coming up here whenever I can, but . . ."

"Oh, wonderful. Then it's settled," he declared. "I'll tell you what I will do: I will continue to write an entire symphony. I'll work all this month, and it will be dedicated to you."

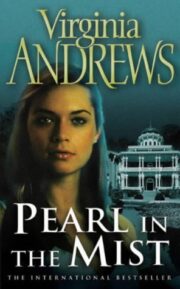

"Pearl in the Mist" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Pearl in the Mist". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Pearl in the Mist" друзьям в соцсетях.