"No matter where you go or what you do, you become Little Miss Special. Even the Iron Lady makes special rules for you and not for everyone else," she complained.

"I don't think Mrs. Ironwood is doing anything for me or is very happy about it anyway," I replied, but Gisselle only saw one thing: I was being permitted to break out of my imprisonment. _

"Well, if any of us get punished, we're going to remind her about this," she threatened, firing her angry gaze at everyone around the table.

After breakfast I left the dorm and got into the car. Buck said very little, except to mutter about how his repair work kept getting interrupted. Apparently no one was happy about my command appearance at the Clairborne plantation. Mrs. Clairborne didn't even appear to greet me. It was Otis who led me through the long corridor to the music studio, where Louis waited at his piano.

"Mademoiselle Dumas," the butler announced, and left us.

Louis, dressed in a gray silk smoking jacket, white cotton shirt, and dark gray flannel slacks, raised his head. "Please, come in," he said, realizing that I was still standing in the doorway.

"What is it, Louis?" I asked, not disguising the note of annoyance in my voice. "Why did you ask that I be brought back here?"

"I know you're angry with me," he said. "I treated you rather shabbily and you have every right to be mad. I embarrassed you and then ran out on you. I wanted you to come up here so I could apologize to you face to face. Even though I can't see you," he added with a tiny smile.

"It's all right. I wasn't angry at you."

"I know. You felt sorry for me, and I guess I deserve that too. I'm pitiful. No," he said when I started to protest. "It's all right. I understand and accept it. I am to be pitied. I remain here, wallowing in my own self-pity, so why shouldn't someone else look at me pathetically and not want to have anything much to do with me?

"It's just that . . . I felt something about you that drew me a little closer to you, made me less afraid of being laughed at or ridiculed—so it was something I know most girls your age would do, especially Grandmother's precious Greenwood girls."

"They wouldn't laugh at you, Louis. Even the crème de la crème, the direct descendants of the Filles de la Cassette," I said with ridicule. He widened his smile.

"That's what I mean," he said. "You think like I do. You are different. I feel I can trust you. I'm sorry I made you feel as if you were summoned to appear in court," he added quickly.

"Well, it's not that, so much as I was punished and . . . ″

"Yes. Why were you punished? I hope it was something very naughty," he added.

"I'm afraid it's not." I told him about my painting trip off campus and he smirked.

"That was it?"

I wanted to tell him more—how his cousin Mrs. Ironwood had it in for me for meeting him—but I decided not to add fuel to the fire. He looked relieved.

"So I pulled a little rank, so what? My cousin will get over it. I've never asked her for anything before. Grandmother wasn't overjoyed, of course."

"I bet you did more than pull a little rank," I said, stepping closer to the piano. "I bet you pulled a little tantrum of your own."

He laughed. "Just a little." He was silent a moment, and then he handed me a few pages of notes. "Here," he said. "It's your song."

At the top of the page was the title "Ruby."

"Oh. Thank you." I put it into my purse.

"Would you like to take a walk through the gardens?" he asked. "Or rather, I should say, take me for a walk?"

"Yes, I would."

He stood up and offered me his hand.

"Just go through the patio doors and turn right," he directed. He scooped his arm through mine and I led him along. It was a warm, partly cloudy morning, with just a small breeze. With amazing accuracy, he described the fountains, the hanging fern and philodendron plants, the oaks and bamboo trees and the trellises erupting with purple wisteria. He identified everything because of their scents, whether it be camellias or magnolias. He had the surroundings memorized according to aromas and knew just when we had reached a set of patio doors on the west side of the house that, he said, opened to his room.

"No one but the maids, Otis, and my grandmother have ever been in my room since my parents died," he said. "I'd like you to be the first outsider, if you like."

"Yes, I would," I said. He opened the patio door and we entered a rather large bedroom, which contained a dresser, an armoire, and a bed made of mahogany. Everything was very neat and as clean and polished as it would be had the maid just left. A portrait of a pretty blond woman was hung over the dresser.

"Is that a painting of your mother?" I asked.

"Yes."

"She was very beautiful."

"Yes, she was," he said wistfully.

There were no pictures of his father or any pictures of his father and mother together. The only other paintings on the walls were of river scenes. There were no photographs in frames on the dresser either. Had he had all pictures of his father removed?

I gazed at the closed door that connected his room with the room I knew must have been his parents' bedroom, the room in which I had seen him curl up in emotional agonythat night.

"What do you think of my self-imposed cell?" he asked.

"It's a nice room. The furniture looks brand-new. You're a very neat person."

He laughed.

And then he turned serious, letting go of my arm and moving to his bed. He ran his hand over the footboard and the post. "I've slept in this bed since I was three years old. This door," he said, turning around, "opens to my parents' bedroom. My grandmother keeps it as clean and polished as any of the bedroom is still in use."

"This must have been a nice place to grow up in," I said. My heart had begun to pitter-patter, as if it sensed something my eyes had missed.

"It was and it wasn't," he said. His lips twisted as he struggled with his memories. He moved to the door and pressed his palm against it. "For years and years, this door was never locked," he said. "My mother and I . . . we were always very close."

He continued to face the door and speak as if he could see through it into the past. "Often in the morning, after my father had gotten up to get to work, she would come in and crawl up beside me in my bed and hold me close so I could wake up in her arms. And if anything ever frightened me . . . no matter how late or early, she would come to me or let me come to her." He turned slowly. "She was the only woman I have ever laid beside. Isn't that sad?"

"You're not very old, Louis. You'll find someone to love,' I said.

He laughed a strange, thin ugh.

"Who would love me? tt not only blind . . I’m twisted, as twisted and ugly as the Hunchback of Notre Dame?"

"Oh, but you're not. You're good-looking and you're very talented."

"And rich, don't forget that."

He walked back to the bed and took hold of the post. Then he ran his hand over the blanket softly.

"I used to lie here, hoping she would come to me, and if she didn't come on own, I would pretend to have been frightened by a bad dream just to bring her here," he confessed. "Is that so terrible?"

"Of course not."

"My father thought it was," he said angrily. "He was always bawling her out for spoiling me and for lavishing too much attention on me."

Having been someone who never knew her mother, I couldn't imagine being spoiled by one, but it sounded like a nice fault.

"He was jealous of us," Louis continued.

"A mother and her child? Really?"

He turned away and faced the portrait as if he could see it. "He thought I was too old for such motherly attention.

She was still coming to me and I was still going to her when I was eight . . . nine . . . ten. Even after I had turned thirteen," he added. "Was that wrong?" he demanded, spinning on me My hesitation put pain in his face. "You think so too, don't you?"

"No," I said softly.

"Yes you do." He sat on the bed. "I thought I could tell you about it. I thought you would understand."

"I do understand. Louis. I don't think badly of you. I'm sorry your father did," I added.

He raised his head hopefully. "You don't think badly of me?”

"Of course not. Why shouldn't a mother and a son comfort and love each other?"

"Even if I pretended to need the comfort just so she would come to me?"

"I guess so," I said, not quite understanding.

"I'd open the door a little," he said, "and then I would return to my bed and lay here, curled up like this." He spread himself out and folded into the fetal position. "And I'd start to whimper." He made the small sounds to illustrate. "Just go over to the door," he said. "Go ahead. Please."

I did so, the pitter-patter of my heart growing stronger, faster, as his actions and words became more confusing. "Open it," he said. "I want to hear the hinges squeak."

"Why?"

"Please," he begged, so I did so. He looked so happy. "Then I would hear her say, 'Louis? Darling? Are you crying, dear?'

"Yes, Mommy,' I would tell her.

“Don't cry, dear,' she would say." He hesitated and turned his head in my direction. "Would you say that to me? Please?" he asked me.

I was silent.

"Please," he pleaded.

Feeling foolish and a bit frightened now, I did so. "Don't cry, dear."

"I can't help it, Mommy." He held his hand out. "Take my hand," he begged. "Just take it."

"Louis, what . . ."

"I just want to show you. I want you to know and to tell me what you think."

I took his hand and he pulled me toward him.

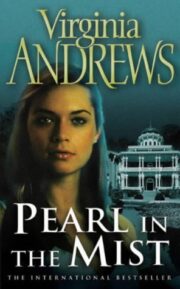

"Pearl in the Mist" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Pearl in the Mist". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Pearl in the Mist" друзьям в соцсетях.