"He might not be too far off thinking that. You heard Mrs. Clairborne's speech about the traditions we must uphold and how we must behave."

"Did you notice that all the clocks were stopped, even the watch around her neck?"

"No," Abby said. "Were they?"

"All at the same hour and minute: at five after two."

"How strange."

"I was going to ask Mrs. Penny about it, but when she became so agitated over my side trip and my meeting Louis, I decided not to add anymore pepper to the gumbo."

Abby laughed.

"What?"

"Every once in a while your Cajun background sneaks back," she said.

"I know. Louis could detect my accent and knew I was from the bayou. He was surprised I was permitted to enroll, considering I wasn't a true blueblood."

"What do you suppose would happen to me if they found out the truth about my past?" Abby said.

"And what truth is that?" Gisselle demanded.

We both spun around and gasped at the sight of her in our doorway. We were so engrossed in our conversation that we hadn't heard her open the door—or else, knowing her, she had opened it softly just so she could spy on us. She wheeled herself into the room, and I sat up in my bed.

"Having a heart to heart, girls?" she teased.

"You should knock before coming in here, Gisselle. You want your privacy, I'm sure."

"I thought you'd be happy to have me come by. I happen to have found out the story of poor Louis," she said, smiling her Cheshire cat smile. Actually, she reminded me more of the sort of muskrat Grandpère Jack trapped.

"And how did you do that?"

"Jacki knew. Seems it isn't all as big a secret as Mrs. Penny pretended. There are skeletons in Mrs. Clairborne's closets," she sang gleefully.

"What sort of skeletons?" Abby asked.

"What's your secret first?"

"Secret?"

"The thing you don't want Mrs. Ironwood to discover about you. Come on, I heard what you said."

"It's nothing," Abby said, her face turning crimson.

"If it's nothing, tell it. Tell it or I'll . . I'll make up something."

"Gisselle!"

"Well, it's a fair trade. I'll tell you what I learned, but you've got to tell me something too. I just knew you'd share secrets with her and not with your own twin sister. You probably told her things about us too."

"I did not." I looked at Abby, whose face was drooping with sadness, both for me and for herself. "All right, we'll tell," I said. Abby's eyes widened. "Gisselle can keep a secret. Can't you?"

"Of course. I know more secrets than you'll ever know, especially about the kids back in our old school, even secrets about Beau," she added happily.

I thought a moment and then blurted something I knew Gisselle would accept.

"Abby was suspended once for being caught with a boy in the basement of one of her previous schools," I said. Abby's surprise worked perfectly, because it looked like I had betrayed her. Gisselle gazed from her to me skeptically for a moment and then laughed.

"Big deal," she said. "Unless," she added, "you were naked when you were caught. Were you?"

Abby looked to me for a moment and then shook her head. "No, not completely."

"Not completely? How much then? Did you take off your blouse?" Abby nodded. "Your bra?" Abby nodded again. Gisselle looked impressed. "What else?"

"That's all," Abby said quickly.

"Well, well, little Miss Goody Goody isn't so pure after all."

"Gisselle, remember, you promised."

"Oh, who cares? That's not enough to interest anyone anyway," she said. She thought a moment and then smiled. "Now I suppose you want me to tell you why Louis is blind and what happened to his parents."

"You said you would," I replied.

She hesitated, enjoying her hold over us. "Maybe later, if I feel like it," she said and spun herself around in her chair and wheeled herself out of our room.

"Gisselle!" Abby cried.

"Oh, let her go, Abby," I said. "She'll just tease us and tease us."

But I couldn't help wondering myself what it was that had turned that handsome young man into a blind, melancholy soul, revealing his feelings and thoughts only through his fingers on the keys of a piano.

6

A Surprising Invitation

Despite my having enough curiosity to fill the eyes of a dozen cats, I didn't give Gisselle the satisfaction of pleading with her to tell us what she had found out, and I certainly didn't go to Jacki. But as it turned out, I didn't have to beg anyone in Gisselle's fan club.

Right after breakfast the next morning, I was called to the telephone to speak to my art teacher, Miss Stevens.

"I was on my way out today to do some work and thought of you," she said. "I know this place just of the highway where we can get a wonderful view of the river. Would you like to come along?"

"Oh yes, I would."

"Fine. It's a bit overcast, but the weatherman guarantees us it will clear up shortly and warm up another ten degrees. I'm just wearing a sweatshirt and jeans," she said.

"So am I."

"Then you're ready. I’ll be by in ten minutes to pick you up. Don't worry about supplies: I have everything we'll need in the car."

"Thank you."

I was so excited by the prospect of drawing and painting scenes in nature again that I nearly bowled Vicki over in the corridor. She had her arms filled with books she had just taken out of the library.

"Where are you going so fast?" she asked.

"Painting . . . with my teacher . . . sorry."

I hurried into our room and told Abby, who was curled up on her bed reading her social studies assignment.

"That's great," she said. I started to change from loafers to a pair of sneakers. "You know, I never noticed that string around your ankle," Abby remarked. "What is it?"

"A dime," I replied, and I told her why Nina had given it to me. "I know you think it seems silly, but . . ."

"No," she said, her face dark, "I don't. My father secretly practices voodoo. Remember, my grandmother was Haitian. I know some rituals and . . ." she said, getting up and going to the closet, "I have this." She plucked a garment out of her suitcase and unfolded it before me. It was a dark blue skirt. I thought there was nothing remarkable about it at first, and then she moved the skirt through her fingers until I saw the tiny nest woven with horsehair and pierced with two crossed roots sewn into the hem.

"What's that?" I asked.

"It's for warding off evil. I'm saving this for a special occasion. I'll wear it when I fear I am in some sort of danger," she told me.

"I never saw that before, and I thought Nina had shown me just about everything in voodoo."

"Oh no," Abby said, laughing. "A moma can invent something new any time." She laughed. "I was hiding this from you because I didn't want you to think me strange, and here you are, wearing a dime on your ankle for good gris-gris." We laughed and hugged just as Samantha, Jacki, and Kate came wheeling Gisselle past our doorway.

"Look at them!" my twin cried, pointing. "See what happens when you don't have boys at your school."

Their laughter brought blood to both our faces.

"Your sister," Abby fumed. "One of these days I'm going to push her and that wheelchair over a cliff."

"You'll have to get in line," I told her, and we laughed again. Then I hurried out to wait for Miss Stevens.

She drove up a few minutes later in a brown jeep with the cloth top down, and I hopped in.

"I'm so glad you can come," she said.

"I'm glad you asked me."

She had her hair in a ponytail and the sleeves of her sweatshirt pushed up to her elbows. The sweatshirt looked like a veteran of many hours of painting, because it was streaked and spotted with just about every color of paint. In her beat-up jeans and sneakers, she looked hardly more than a year or two older than me.

"How do you like living at the Louella Clairborne House? Mrs. Penny is sweet, isn't she?"

"Yes. She's always jolly." After a moment I said, "I switched roommates."

"Oh?"

"I was rooming with my twin sister, Gisselle."

"You don't get along?" she asked, and then she smiled. "If you think I'm getting too personal . . ."

"Oh no," I said, and I meant it. I remembered Grandmère Catherine used to tell me your first impressions about people usually prove to be the truest because your heart is the first to react. Right from the beginning I felt comfortable with Miss Stevens, and I believed I could trust her, if for no other reason than the fact that we shared a love of art.

"No, I don't get along with her," I admitted. "And not because I don't want to or I don't try. Maybe if we had been brought up together, things would be different."

"If?" Miss Stevens's smile melted with confusion.

"We've only known each other a little more than a year," I began, and I told her my story. I was still talking by the time we arrived at the place that overlooked the river. She hadn't said a word the whole time; she just listened quietly.

"And so I agreed to come to Greenwood with Gisselle," I concluded.

"Remarkable," she said. "And I used to think my life was complicated because I was brought up by nuns at an orphanage, St. Mary's in Biloxi."

"Oh? What happened to your parents?"

"I never really knew. All the nuns would tell me was that my mother gave me over to them shortly after I was born. I tried to find out more about myself, but they were very strict about keeping confidences."

I helped her set up our easels and put out paper and drawing utensils. The sky had begun to clear, just as the weatherman had promised, and the thick layers of clouds separated to reveal a light blue sky behind them. Here at the river, the breeze was stronger. Behind us the branches of some red oak and hickory trees shuddered and swayed, sending a flock of chirping sparrows off over the riverbank and then into a quieter section of cottonwoods.

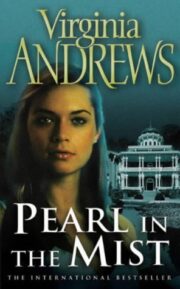

"Pearl in the Mist" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Pearl in the Mist". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Pearl in the Mist" друзьям в соцсетях.