So it seemed to her, Martha thought, that in 1774 a clock had struck somewhere and it was time to get up from their quiet life of family and home and watching the river flow past the foot of the hill, and step out the door and into the War.

The War had ended four years ago. But as she shook out the folds of her dark skirts, and glanced at her looking-glass to make sure her cap was straight, it seemed to Martha that the War was once again waiting downstairs, as alive as it ever had been. Ready to sink its claws into George and drag him away from her.

Drag them both away, never to return.

Never, she vowed in her heart. I saw what it did to them—to Fanny, to Jacky, to those children whom I most love.

He promised, and I will hold him to that promise. Nothing—nothing—will take us again from this place, and from these people who need us.

As she came down the stairs into the paneled shadows of the hall, Martha heard James Madison’s voice in the West Parlor. Barely a murmur from that small slight man, like a mouse nibbling in a wainscot. A wet, rasping cough told her Madison was talking with George’s nephew Augustine—Fanny’s husband, about whose health Martha was increasingly worried.

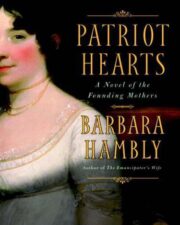

"Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers" друзьям в соцсетях.