“Indeed I don’t,” she agreed, and handed him a farthing. “And the rest when we’re safely across the road.” Far from being offended, the boy gave her a dazzling grin and leaped into the traffic with his birch-broom, carving a path through the trampled swamp of dung while he dodged drays, riders, and the fast-moving phaetons of the rich. According to Abigail’s closest London friend Sarah Atkinson, hundreds of parentless children slept under the bushes in the Park, or beneath the arches of the public buildings. They died of pneumonia every winter like the sparrows that fell from the frozen branches.

“You should be in school,” she informed the boy, handing him the second installment of the fee when Briesler, in his stout boots, had steadied her across the slippery cobblestones to the far corner. “Surely you don’t plan to still sweep a crossing when you’re grown?”

The child took the coin with unimpaired cheer. “Lor’ no, ma’am. When I’m growed I’ll take the King’s shillin’ an’ be a soldier.”

Before she could reply he gave her a brisk salute, and dashed away to proposition his next customer, a stout gentleman emerging from a wine-shop. And where will your King send YOU, Abigail wondered, the next time he needs to avenge ninety thousand dollars’ worth of ruined tea?

As she’d feared, her son-in-law had sacked the cook, and the young maidservant who answered the door at 10 Wimpole Street had the flustered look of one overwhelmed with too many jobs. “Ma’am, I’m that glad to see you, and so will Mrs. Smith be, too,” exclaimed the girl as she opened the door, forgetting the cardinal rule that good servants were both invisible and mute. English servants, anyway—Abigail had never encountered an American servant who didn’t think himself or herself the equal of their employer. “We sent Katie—that’s the kitchenmaid, ma’am—out for the midwife, and she should be here any time now.”

“Mama!” Colonel William Smith came striding down the stairs, holding out his hands to grasp Abigail’s. “Thank God you’ve come!” Big, dark, and flamboyantly handsome, Colonel Smith looked concerned but not scared. When he kissed Abigail, his breath smelled of brandy.

“When did her pains begin?” asked Abigail, and her son-in-law looked completely nonplussed. “You’re a soldier and you didn’t note the time of the battle’s opening guns? Shame, sir.”

“Eight o’clock or thereabouts,” provided the maid. “And nobbut a few moments long. I’ve got water on the boil, and made her some tea.” And snatching up the apron she had clearly stripped off and dropped onto the hall table moments before opening the door, she vanished down the kitchen stairs again.

The house, Abigail observed as Colonel Smith escorted her volubly up the stairs, though a third the size of 8 Grosvenor Square, was ill-kept and a trifle dirty, and, as she’d feared, freezing cold. No one had cleaned the lamp-chimneys in days, and every candle-holder bore a burned-down stump of melted wax. Wax, she noted, and not the less expensive tallow that Abigail bought for every room in her own house where the smell of them wouldn’t be detected by guests.

She understood, of course, the need to keep up appearances, but she knew also what Colonel Smith was paid as John’s secretary. Though a hero of the War, the handsome New Yorker had no family money, a fact which had not entered into the discussion when Smith had asked for Nabby’s hand. And indeed, in a new nation, with the Colonel’s obvious ambition and drive, family money was less important. John’s father had been a farmer, like the Colonel’s, and a ropemaker in his spare time.

At all events, a cheerful fire burned in the bedroom where Nabby sat, propped among pillows, on a sheet-draped chair before the blaze. In spite of herself Abigail glanced at the sides of the hearth. She was relieved to find that it, at least, had been swept the previous day.

“Mama…” Nabby caught her mother’s hands, and Abigail dropped to her knees to hold her.

It was as if the stiff, withdrawn silences, the indifferences of the war years had never been.

Abigail didn’t know how she could have endured the War, if it had not been for Nabby at her side. Nabby had turned nine four months before the tea was dumped in Boston Harbor; the first shots were fired at Lexington bridge three months before her tenth birthday. When a man weds, he gives hostages to fortune, John Dryden had said a century and a half before. Unspoken in Abigail’s partnership with John was the promise that it was she who would keep those hostages safe.

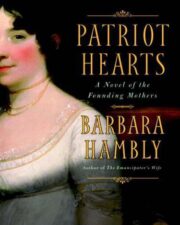

"Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers" друзьям в соцсетях.