“You must be strong,” she’d said to them, when with fall of darkness the voices of the men assembled outside Old South grew louder. She gathered them close to her on the bed, Charley and Nabby and Johnny, and Tommy a babe in the crib. “I expect all of you to be strong, to be worthy and to serve your country as your father is doing.”

God help them, she had thought, they will need strength, if anything goes wrong. If something happens to John.

When Johnny and Charley had been put to bed, Nabby remained in Abigail’s room, reading to her. Her young voice had barely paused, when torchlight had streamed past the window; she had not even looked up. Abigail had wanted to ask her then if she still had nightmares, but could not.

Later, when John had come in and Nabby had run to him to silently clasp him round the waist, he had laid a hand on her head but looked over her at Abigail. He had said only, “The die is cast.”

A scruffy little boy dressed in men’s cast-offs darted up to Abigail at the corner of Marylebone Road and offered, for a halfpenny, to sweep the crossing: “Fine lady like you don’t want to get ’er clogs all shitty,” he explained with a winning smile. He didn’t look any older than Johnny had been when the fighting started with England, and was probably as illiterate as Abigail’s finches.

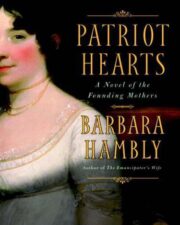

"Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers" друзьям в соцсетях.