She was still there, and the last of the shouting was just dying down in the hall, when she heard Paul Jennings gasp, “Mr. Madison, sir!”

Stepping quickly through the parlor door she saw the little white-haired gentleman stagger, then sink onto one of the hall benches as if he’d been shot. The men with him crowded around, supporting him and jabbering, Sophie thought, like so many frightened monkeys. She crossed unhurriedly to the dining-room, poured a glass of champagne, and brought it back out.

“Drink this, sir.”

The thin white fingers could barely keep a grip around the stem, but he glanced up and met her eyes and there was nothing weak or beaten in his sharp glance. “Mrs. Hallam.” He shook the others off him—the senior Charles Carroll, whose son had so recently hustled Dolley out of the Mansion, and one of his generals—and stood to bow.

“Mrs. Madison left safely about half an hour ago,” reported Sophie calmly—she had always liked Mr. Madison. “And as you see—” She gestured at the shadowy front hall, strewn with Dolley’s dresses and shawls, with broken china and sweetly reeking puddles of spilled wine, “—the looters were a bare ten minutes behind.”

“I hope you managed to secure something worthwhile for yourself, ma’am?”

“Only memories.”

“Ah.” Madison sank back onto the bench, closed his eyes. “A woman of discernment.” His black clothing was gray with dust, his white hair and dead-white exhausted face, blackened with powder-smoke.

“Dolley, on the other hand, carried off all the Cabinet papers, a small clock, General Washington’s portrait, and the drawing-room curtains, so as you see, she exhibited more discernment than I. Will you lie down, sir?”

“Lie down?” exploded old Mr. Carroll. “Dammit, woman, the British are on our heels—!”

“I see no sign of them on the Avenue,” Sophie retorted coolly. “And I believe Mr. Madison would be the better for twenty minutes’ rest.”

“The lady is right, sir,” affirmed Mr. Barker, kneeling to hold the wineglass again to Madison’s lips. “I think those louts about cleared out the cellar, sir, but I’ll have a look round for cognac if thou’rt mindful for it.”

Madison shook his head. “I see things have much changed since the days of the Revolution,” he murmured. “I would not have believed the difference between a militia force and regulars, had I not seen it today.”

“I think it’s the British who have changed, sir,” replied Sophie. “Since last Americans fought them, they have sharpened their steel against Napoleon. And the generation that has grown up here since that time has done nothing but call one another names.”

“They’ll rally,” said the General bracingly. “Of course they’ll rally. And men will come into the city to defend it—”

Madison lifted his fingers, shook his head without opening his eyes.

After a moment, Sophie said, “Mrs. Madison has gone on to Bellevue with your son, Mr. Carroll.”

“Too close,” Madison breathed. “The British will pass over this city like breaking surf and follow our troops on into Georgetown. Will you be going out there, too, Sophie?”

“Later, yes.”

“I must find General Winder—rally the men. Keep the government together.” He drew a deep breath and coughed, flinching with pain. Sophie, who had sat with Abigail Adams through bouts of her rheumatism, knew just how agonizing was that net of fire that seemed to clothe bone and muscle beneath the skin. “Should you see my wife before I do, let her know we’ll rendezvous at Salona Plantation. It’s ten miles up the river and she should be safe there.”

“You should rest,” said Sophie again, and the old man waved slightly, brushing the suggestion away.

“Since first the British learned they could not hold us by force,” he said, “they’ve been trying to hold us by other means: all the usual tricks that the strong play on the weak. Debt. Extortion. Isolating us from support elsewhere. Bullying. There always comes a time when the bullied must hold the line and say, No more. There is never any going back, but what we strive for now is to choose our own path forward, not the path that is most convenient for the merchants and bankers who surround the English King.

“They could not conquer us before but they can break us apart. Once union is sundered—once the government centered in this city shatters—we can be dealt with piecemeal. Each State will go back to being England’s handmaiden, now that France and Spain are broken. Sending our men to die in wars of her choosing; paying money to her rather than investing it in ourselves. Tonight—and in the next few weeks—we will need to hold fast.”

He sighed, and sat up. An unlikely-looking kingmaker, thought Sophie, to have maneuvered first Washington and then Jefferson into leading the raw new nation in the direction he believed that it should go.

But he was no Richelieu, she thought. When the enemy turned up again, he had mounted his horse and ridden to the battlefield, something not even Washington had done as President. And had it been necessary, she understood, looking down at him, he would have died under the British guns.

“I hope Dolley understands,” he said, and Sophie smiled.

“She spoke of defending this house with Patsy Jefferson’s Tunisian saber.”

His grin was bright as a boy’s. “That’s my Dolley.”

It was yet daylight when they left the Mansion, the last rays of the sun sickly yellow beneath the blackness of the coming storm. Sophie helped Paul Jennings lock up the doors for what she knew was going to be the last time.

Then the young man set off on foot for the Georgetown ferry, and Sophie went back to her house on Connecticut Avenue, to ready her own gig for a drive.

Not long after that, the British came.

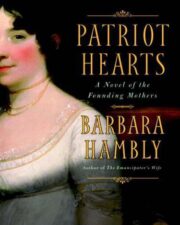

"Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Patriot Hearts: A Novel of the Founding Mothers" друзьям в соцсетях.