There was nothing to do but accept the position. The Black Prince was married at last and to his sweetheart of years ago. Neither of them was in their first youth but there were a few years ahead for childbearing. How could fate be so cruel!

Of course there was some delay. But Joan and the Prince snapped their fingers at ceremonies. At least Joan did and Edward followed her. But in due course the papal dispensation arrived and in October the espousals were celebrated at Lambeth by the Archbishop of Canterbury. That Christmas Joan and Edward entertained the entire royal family at their home in Berkhamsted; and the people from the surrounding country joined in the festivities. It was a great occasion, the marriage of the Black Prince, which was all the more to be enjoyed because it had been delayed so long.

After Christmas great preparations were afoot for the Prince and his family to leave for France. The King had made him Prince of Aquitaine and Gascony and he was to set out with his wife and entourage for Bordeaux.

During that very month when Edward and Joan sailed for Bordeaux, Matilda, Blanche’s sister, arrived in England to take possession of her inheritance.

She had not been more than a few weeks in England when she caught the plague and within a day or so was dead.

Blanche was now her father’s sole heiress and the entire Lancastrian fortune, by courtesy of her marriage, was in the hands of John of Gaunt.

He reflected with Isolda on the strangeness of fate which seemed determined to shower blessings on him with one hand and take them away with the other.

So there he was rich beyond his dreams but his path to the throne it seemed blocked for ever by Edward’s marriage to the lusty Joan.

He considered the situation with Isolda. Joan was two years older than her husband; but she had already borne five children and could bear Edward sons. Once she did that – one or two boys … that would be the death knell of his hopes.

‘The greatest man in the kingdom …’ crooned Isolda.

‘Next to the King and my brother of Wales. There is also Lionel.’

He was in possession of the earldom of Richmond, of Derby, Leicester and of course Lancaster. His father, delighted at the turn of events, rejoicing in his foresight in arranging the match with Blanche of Lancaster, decided to make him a Duke, and one dull November day John knelt before his father and was girded with the sword, and the cap was set on his head while he was proclaimed a Duke – Duke of Lancaster.

More than ever he longed for a son but when Blanche was next brought to bed, she was delivered of a daughter. He could have wept with mortification, though he kept his disappointment from Blanche.

They called the girl Elizabeth and he loved her even as he loved her elder sister Philippa, but he went on longing for a boy.

His bitterness was great when news came from Aquitaine that Joan had produced a fine boy. There was great rejoicing throughout the court and the country. It was fitting that the Black Prince should give the country an heir who would be exactly like himself. They christened the boy Edward. There was a feeling that that was a kingly name. People forgot that there had been one Edward – the Second – who had been slightly less than kingly. The Prince was there to step into his father’s shoes, already loved and revered by the people – and he had not disappointed them. There was another Edward and a little one in his cradle to grow up in the light of his father’s wisdom – a little king in the making.

John curbed his disappointment. He would have hated Blanche to know his feelings. His love for her was idealised, as was hers for him.

He could talk to Isolda about the new turn of events, but she continued to look wise – almost as though she were some soothsayer who could see into the future. He half believed that she feigned this for his pleasure; but sometimes he felt that she had some insight and she continued to insist that there was a crown close to him.

Blanche was once more pregnant. So was Joan of Kent.

The King was in close conversation with his son and on the table before him lay letters from Bordeaux.

‘Your brother is eager that you should join him,’ said Edward, ‘and I am sure when you know the reason you will be eager to do so. The King of Castile is at Bordeaux.’

John knew that there was trouble in Castile, because Henry of Trastamare, Pedro’s bastard brother, had for some time believed he had a right to the throne and would rule better than Pedro.

‘Henry of Trastamare now reigns in Castile and Pedro is asking our help to regain his throne,’ went on the King.

‘Is it any quarrel of ours?’ asked John.

‘Your brother believes and I with him that it is no good thing for bastards to depose legitimate heirs. Moreover Pedro has promised to make little Edward King of Galicia and to reward well those who help him.’

‘If he can be trusted that seems fair enough.’

‘I am sure your brother agrees with that. He asks that you join him there. My dear son, it is my wish that you make preparations to leave without delay.’

John bowed his head. He was not averse to the adventure and it was true that legitimate sons could not stand aside and allow bastards to triumph. It was a dangerous precedent.

Blanche was apprehensive when he told her he must prepare to leave, but as the Queen pointed out to her women in their positions must learn to accept these separations.

Bravely Blanche said her farewells. ‘And when you come back,’ she added, ‘I trust I shall have a fine son to show you.’

‘We’ll have him yet,’ replied John. ‘Never fear. Isolda swears it and she is a wise woman.’

So he left her and sailed for Brittany and when he reached the shores of that country, a message awaited him from his brother.

‘On the morning of Twelfth Day Joan bore me another son. The child was born in the Abbey of Bordeaux. A boy. God be praised. A brother for little Edward. Truly I am pleased in my marriage. There is great rejoicing here at the coming of Richard of Bordeaux.’

John ground his teeth in envy. Another boy. Another to stand between him and the throne.

Whatever Isolda said fate was mocking him.

Blanche had decided that her child should be born in the Lancastrian castle of Bolingbroke. This had been one of her father’s castles which was now in the hands of her husband. She had always had a fancy for the place although many of the servants believed that it was haunted. A very strange kind of ghost was this one. It was said to be the spirit of some tormented soul which took the shape of a hare which had been seen running through the castle and some swore they had been thrown by it as it passed swiftly between their legs.

Blanche remembered her father’s telling how a pantler of the castle who had once tripped while carrying wine had blamed the hare, but it seemed more likely that he had been indulging too freely in the cellars.

There was an old story that once some bold spirits had gathered together a pack of hounds to hunt the hare. They had pursued it through the rooms of the castle down the spiral staircases to the cellars. Then the hounds had come dashing out, mad to escape, their hair on end, their eyes wild and none of them would enter the castle again.

In all her sojourns at the castle Blanche had never seen the hare and as the fancy had come to her to visit Bolingbroke, hither she had come and decided that it should be the birthplace of her child.

Here she awaited the event and thought constantly of John, praying to God and the saints to bring him safely through the battle.

She sent for Isolda who was a great comfort to her, for she believed that Isolda had some rare gift of looking into the future. Isolda was sure that her beloved John was coming home safely. She was sure too that this time there was going to be a healthy boy.

So while the winter days grew a little longer and the signs of spring increased with passing time, Blanche waited at the Castle of Bolingbroke for the birth of her child.

On the battle field of Nájara the Black Prince with his brother John of Gaunt was ready to fight the cause of Pedro of Castile.

Against them was the army of Henry of Trastamare. ‘This day,’ the Prince had said to Pedro, ‘we shall decide whether or not you are to have your throne.’

He had begun to doubt Pedro. Henry of Trastamare had written to him in a manner which seemed frank and plausible. Pedro was known throughout Castile as The Cruel. He had shed much innocent blood. Legitimate he might be but Castile suffered under him and the people of Castile would be overjoyed to see him deposed. The great Black Prince had no notion of the man he was dealing with. If he really knew Pedro the Cruel he would recognise him as a false friend.

‘Ha,’ said the Prince, ‘it is clear that Bastard Henry has no stomach for the conflict. The battle is as good as won.’

So they rode forward and there was not a man in Henry of Trastamare’s ranks who was not aware that that military legend the Black Prince came against them and in their hearts they knew that the hero of Crécy and Poitiers was undefeatable.

They saw him there, at the head of his army, his black armour making him easily identifiable.

From the moment they heard his shout: ‘Advance, banner in the name of God and St George. And God defend our right!’ the result was a foregone conclusion. All knew that the Black Prince was the greatest soldier in the world next to his father and his great-grandfather; and the former was growing old and the latter was dead. He had gathered under his banner the flower of English chivalry and there was not a man who did not regard it as the greatest honour to serve under him.

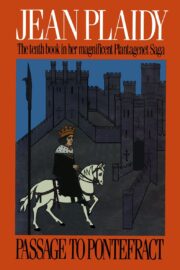

"Passage to Pontefract" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Passage to Pontefract". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Passage to Pontefract" друзьям в соцсетях.