She would never forget their last night together. There had been that terrible indecision which had obsessed him. But she had known that he would go. He had to go. He loved her, yes, but he was a man with a vision. Ambition there would always be, and he must serve it.

So now there she was, a lady of the manor, well cared for. He had seen to that. Her jewels would keep her for the rest of her life if need be. He would put their sons in high places. Even Thomas, her son by Hugh Swynford, had his niche and was with Henry of Bolingbroke. John, Henry and Thomas Beaufort would be even better provided for. She had no fears on that score.

But none of this could ease her melancholy.

She had her attendants; she lived like a lady in her manor, looking to her household, with plenty to minister to her needs. And here in the country now and then news came from Court of the young King’s conflict with his uncle of Gloucester and she thought: At least John is spared those troubles.

She had heard that the young King had come near to being driven from his throne, but a year had passed since, mercifully, those troubles had blown over and he was now in control.

He had taken firm action; he had reminded those about him that he was twenty-one years old. He would have no more regencies, he said. He would rule himself.

The country had grown quieter and there had been no more disturbing rumours for some time.

So life went on – one day very like another. So will it be until the end of my days, thought Catherine. I shall grow old and if he did come back he would not know me.

But it was not to be so.

One misty November day when she had set aside her needlework because the light was so bad, she was startled by the arrival of visitors.

This was a somewhat rare occurrence and always welcomed. It was stimulating to hear news of the outside world.

She was a good housewife and there were always pies in the larder, for there were many in the household to be fed and she liked to be prepared should any travellers call and there was a constant stream of beggars to come pleading for a bite to eat and she never refused them.

She went down to the courtyard. A man leaped from his horse and as she looked at him she thought she was dreaming.

He stood still gazing at her while she stood as though rooted to the ground.

Then he said: ‘Catherine. You have not changed one small bit.’

He held out his hands and they were in each other’s arms.

So he was back. The world was suddenly gay. It was bleak November but it was spring to her. She was wild with joy. She called throughout the house: ‘Fires must be lighted. Flesh must be roasted. The best … the very best. My lord has come home.

‘I shall die of joy,’ she told him.

‘I too,’ he answered.

He must look at her. He must touch her hair, her soft white skin.

‘So often have I done so in my dreams,’ he said.

Nothing had changed. They were the same passionate lovers as they had been when they had first met. There was so much to know. So much to learn.

They must love and they must talk. He must not go away again.

He would not, he promised her. From now on they would be together always.

‘You do not know how near I came to staying, to abandoning all my hopes of Castile for your sake.’

‘Ah, John, I knew,’ she answered. ‘But I knew too that you would go.’

‘Those lonely years … barren of love!’

‘Perhaps they will come again,’ she said.

He shook his head.

‘I shall never leave you again, Catherine,’ he said solemnly.

‘You will never cease to want a crown,’ she said. ‘I know you well. You love me, but ambition is there. It was born in you. You are the son of your father. He sought the crown of France … hopelessly it seems now, and you will always seek that of Castile.’

He smiled at her. He had much to tell her, then she would understand. He wanted news of their children. His aim was to legitimise them. Yes, he was going to do it one day. Richard would agree. He must tell her that Richard had wished him to come home, had asked him to come home.

‘He does not trust my brother Gloucester.’

‘Oh John, there will be this strife again. There was a time after you had gone when there was talk of war … war here in England. The barons rising against the King.’

‘I know … I know. Since the time of John such things have been spoken of. Then there was my grandfather. Once a King is deposed, it is remembered. History can repeat itself. Never fear. Richard will stay on the throne. I think he liked me better after I had gone … that is he preferred me to my brother.’

‘And you, John, you dreamed of a crown. You wanted a crown. And Castile …’

‘Good news from Castile, Catherine.’

She could scarcely believe it. Castile was no longer a menace. It had come about as John said, in a most natural way. The happiest way to settle all disputes between countries was through marriage.

‘I fear, Catherine, you will never see my daughters Philippa and Catherine again. Unless of course you travel to Castile and Portugal or they visit us here. Your charges are wives now, my dearest. What think you of that!’

‘It seems to please you so I suppose I must be pleased.’

‘I married Philippa to my ally João of Portugal. A wise move. I was not sure that I could trust him but the alliance put a seal to that.’

‘And Philippa is happy?’

‘Philippa is Queen of Portugal.’

Catherine looked at him a little sadly. ‘You set such store by crowns,’ she said; and she thought of little Philippa and her grief when her mother had died and how she and her sister Elizabeth had been as Catherine’s own children. She had loved them as dearly since they were John’s.

‘Philippa was never so well able to take care of herself as Elizabeth was,’ she said.

John frowned and she wished she had not said that for she knew that he’d never liked Elizabeth’s marriage to the King’s half-brother, wild John Holland.

‘The best news of all is what has happened to my daughter Catherine. She has settled the matter of the Castile succession and settled it most satisfactorily.’

‘Catherine …’

‘Your namesake, my dearest. Constanza is happy with the result and so am I. Let me tell you how it came about. The campaign was dragging on. There was trouble all about us. Constanza and I came near to being poisoned.’

She caught her breath with horror.

‘These things will be,’ he said lightly. ‘The King of Portugal had fallen dangerously ill and it really seemed as though he were on his deathbed. Then we began to suffer the same symptoms. We kept watch and the fates be praised we found the culprit. He was trying to get rid of us.’

‘He was working for Castile?’ asked Catherine.

‘It would seem so. However we had found the root of the trouble and it was amazing how quickly we all recovered. But such incidents sober one. I had come to the conclusion that this battle would never be satisfactorily resolved and it occurred to me that I had a daughter, Juan of Castile had a son. If they married that would settle the matter once and for all.’

‘So much better than those endless wars which give victory to one side and then the other and decide nothing for more than a few weeks.’

‘My wise Catherine. I put out feelers for the match. Juan was not very anxious for it, but we had a stroke of good fortune, for the Duc de Berri was looking for a wife. He wanted a young one and only a lady of nobility would do for such a noble Prince of France. He was a widower and not very young; I had no intention of giving him Catherine but I pretended to consider. And that frightened Juan. He did not want a powerful French claimant for the Castilian throne. He decided he would take Catherine for his little son, Enrique.’

‘And how old is Enrique?’

‘Ten. But Catherine is only fourteen. They are ideally suited.’

Catherine sighed. She herself had made a marriage of convenience with Hugh Swynford and she knew how unsatisfactory such marriages could be.

‘I was very clever, Catherine. I have no intention that Catherine shall lose her right to the throne of Castile. Juan has a second son Fernando and part of the treaty is that Fernando shall remain unmarried until the match has been consummated.’

‘So this matter of Castile is settled and you have ceased to long to be its King?’

‘I have grown older and wiser, sweet Catherine. I tell you truthfully that all through these negotiations I said to myself: If I can settle this matter to the satisfaction of all I shall go home to my Catherine.’

‘And so you did think of me while you made these plans.’

‘All the time I longed for you.’

‘The Duchess?’ she asked quietly.

‘Constanza is pleased that her daughter should be Queen of Castile. She is content, I think. She too is weary of all the conflict.’

‘She knows you have come to me?’

‘She knows it and she makes no protest. She is Castilian at heart. She will never be anything else. She wishes to live with her own people about her. There is no room for me in her life.’

‘As soon as she became your wife she knew of my existence.’

‘I could not keep it from her.’

‘She knew then that your marriage to her was purely for the sake of the crown of Castile.’

‘Marriages such as ours are usually for such reasons.’

‘And she accepts this?’

‘She must. It is life. She does not want me, Catherine. You should have no qualms. Constanza is happy now that Catherine is married to the heir of Castile. Catherine will be Queen of the Asturias. That is all she asks.’

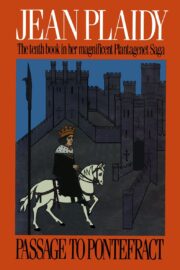

"Passage to Pontefract" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Passage to Pontefract". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Passage to Pontefract" друзьям в соцсетях.