It seemed to them that the masters worked everything out to their own advantage.

And now because of this war with the French which went on and on, there was a new tax – the Poll Tax which people were to pay according to their incomes. Archbishops and Dukes paid six pounds, thirteen shillings and fourpence each and an ordinary labourer was charged fourpence.

In spite of this order the money was not forthcoming and it was necessary to send collectors through the towns and villages to enforce payment.

The law was that every person over fifteen must pay.

Richard had been four years on the throne, and they had been four depressing years. At the end of them the country was in a worse condition than it had been at the death of the old King. The French were troublesome; the Scots were taking advantage of the situation; the bogey of the nation was John of Gaunt who had failed miserably in his expeditions on the Continent. There was a rustling of rebellion throughout the country and it was growing louder. Discontent was rife among the peasants. They were asking each other why it should be that men were condemned to work for others all their lives. Who decided whether a man should be a villein or a lord?

Those in high places were unaware of what was happening. They could not see the gathering storm until it burst upon them.

Chapter IX

WAT TYLER

There was one man who believed so fervently that there was a great deal wrong with life as it was lived in England that he was determined to give his life if necessary to change it.

This was John Ball, a priest who had begun his career in the Abbey of St Mary’s in York. He had very soon found himself in conflict with the authorities because not only did he hold controversial views but he would not stop talking about them.

He had seen what had happened after the Black Death and he deplored the fact that although workers on the land had been seen to be important to the well-being of the country they continued to be treated as serfs; and when their labour was in great demand and there was every reason to suppose they might have asked a higher wage for their services, they had been completely subdued by their masters and forced to work at the same wage as they had received when there were plenty of them.

Why, he asked himself and others, should some, merely on account of where they were born, live on the fruits of other men’s labours?

His watchword was:

‘When Adam delf and Eve span

Who was then the gentleman?’

It was his favourite theme. Had we not all come from Adam and Eve? The scriptures told us so. Why then should some of us be favoured above others?

John Ball was a born preacher. He loved to talk and took a great pleasure in expounding his views to others. He would go to the village green and the people would crowd round him to listen to his sermons. They were different from any other sermons they had ever heard. His views on the Church were similar to those of Wycliffe; but in addition to the reform of the church John Ball wanted the reform of society.

After listening to him the villeins would return to their dark hovels and their meagre fare and would think of the mansion close by in which lived the lord of the manor. He was waited on by countless servants; his table was weighed down with good things to eat. Those who served in his kitchens counted themselves fortunate, for a few crumbs from the rich man’s table fell to them. And yet, argued John Ball, how had this happened? They all had the same forebears, did they not? Adam and Eve? And yet some had been born in mansions, others in dark hovels, some under a hedge maybe.

It was fascinating to listen to him and that which many had accepted before as God’s will, they now questioned.

It was not long before John Ball was noticed, as anyone preaching such a doctrine must be. Moreover whenever he preached, people flocked to hear him. It was disconcerting. More than that. It was dangerous.

On Sundays he would wait until the people came out from Mass and then start preaching in the market square. He had a magnetic quality and many found it impossible to pass on. Moreover his words were so arresting. They had certainly never heard the like before.

One day he was at his usual place and was soon addressing the crowd.

‘My good friends,’ he cried. ‘Things cannot go well in England or ever will until everything shall be in common, when there shall be neither villein nor lord, and all distinctions levelled, when the lords shall be no more masters than ourselves. How ill they have used us! And for what reason do they keep us in bondage? Are we not all descended from the same parents, Adam and Eve, and what reasons can they give, why they should be more masters than ourselves – except perhaps in making us labour for them to spend. They are clothed in velvets and rich stuffs, ornamented with ermine and other furs, while we are forced to wear poor cloth. They have wines, spices and fine bread while we have only rye and the refuse of the straw; and if we drink it must be water. They have handsome seats and manors when we must brave the wind and rain in the field. And, my friends, it is from our labour that they have the wherewithal to support this pomp. What else should you lack when you lack masters? You should not lack for fields you have tilled nor houses you have built, nor cloth you have woven. Why should one man mow the earth for another?’

If John Ball was aware of strangers in the crowd who listened he gave no sign. He did not care who heard him. What he said was truth.

He would go on saying it because he believed it. No matter what befell him, he would go on telling the truth, before the King, before the Pope, before God.

But this could no longer be called the ranting of a mad priest. It was the rumblings of revolt.

John Ball was becoming a menace to security.

It wasn’t long before he received a command to appear before the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Simon of Sudbury – so called because he had been born in the town of that name in Suffolk – had become Archbishop of Canterbury some four years previously. He was a staunch adherent of John of Gaunt and there could not have been a man less like the priest, John Ball. Simon was not one to allow himself to become involved in doctrines; he had been originally disturbed by the rise of John Wycliffe but preferred to forget about him particularly as John of Gaunt was inclined to favour the preacher. But Courtenay, the Bishop of London, was of a very different mettle. There was a man who was going to stand by what he believed in even if he lost his post in so doing.

Simon of Sudbury could well be without these uncomfortable men and such a one was John Ball.

The man stood before him and had the temerity to repeat what he had been saying in market squares. The Archbishop could sense the fiery fanaticism of the man and knew at once that he was dangerous. Such as John Ball should not be allowed to roam the countryside inciting people to revolution.

The Archbishop realised that it was no use admonishing him. He had already been in trouble before. People had been forbidden to attend his meetings – but that had not stopped them. He had been excommunicated, but no one – least of all John Ball – had cared very much about that.

There was only one thing to do with such a man and that was put him away where he could not preach, so the Archbishop sentenced him to a term in Maidstone prison.

Let him stay there where he could do no harm. The people would soon forget him and his dangerous doctrines.

But people did not forget John Ball. His words were remembered. When men laboured in the fields for a pittance, when they wondered where their next meal was coming from and the children were hungry, they remembered John Ball. Why should it be? they asked. They watched the rich ride by on their fine horses with their fine clothes and their attendants. Why? asked the people. How did it happen? Hadn’t they all begun with Adam and Eve? Who was then the gentleman?

Resentment grew when the collectors came round for the tax. Collecting had come to be a somewhat dangerous occupation and only those would enter into it who were promised big rewards.

There was one baker of Fobbing in Essex – a man of great strength who refused to pay the tax and who so terrified the collector that he did not insist.

This baker was talked of throughout Essex and the people of Fobbing made a hero of their baker and would have followed him if he would have led them. But the baker of Fobbing had no desire but to carry on baking his bread and this he did; but he had given them an indication that resistance was not impossible.

One May day the collector called at the house of a tyler in the town of Dartford and demanded payment of the tax.

The man of the house, Walter, was close by at his work tyling a house, and two women, his wife and daughter, were alone.

The collector demanded the tax not only of the mother but of the girl, at which the woman said: ‘My daughter is not yet fifteen years of age and therefore pays no tax.’

‘What?’ said the collector casting a lascivious eye on the girl. ‘That one not fifteen!’

He approached the girl and took her chin in his hand. He forced her to look at him. She was trembling with fear. Her mother looked on with horror, for she had heard tales of how these collectors could behave and that there was no redress against them because they were working for the government and it was not easy to get men to take on the disagreeable task of collecting.

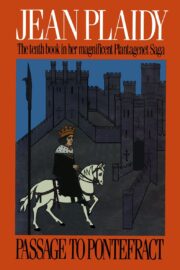

"Passage to Pontefract" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Passage to Pontefract". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Passage to Pontefract" друзьям в соцсетях.