However, since it was so, John must not shut his eyes to the facts.

The King was surrounded by advisers and three days after the coronation his new Council was elected.

This had been done with great care so that every party was represented. The King’s uncle Edmund headed the list; William Courtenay the Bishop of London was another; and the choice of the rest had been made so carefully that for every supporter of John of Gaunt there was one from the opposite party.

It was significant that John of Gaunt was not included. He would not show that he resented this. Nor did he very much. Edmund would do exactly as he told him and he would rather act through his brother than directly.

In the new Parliament there was a majority of members who had been in the Good Parliament which had opposed him, and Sir Peter de la Mare had been chosen as the speaker.

Of course a man such as John of Gaunt – the richest in the country and the first in importance after the King by birth – could not be ignored altogether and when an advisory committee was set up, John’s name appeared at the top of the list.

This list was read out in the presence of the King, and John created a dramatic incident when, to the astonishment of all present, he rose from his seat and walked to the throne on which the young King was seated.

There was a tense silence in the House, and when John spoke all could hear clearly what he said.

‘My lord King, I pray humbly that you will listen to my words. I speak out of concern not only for you as my sovereign but for your own person. The Commons have chosen me to be one of your advisers, but this I cannot accept until I have cleared myself of charges made against me. Calumnies have been uttered. These are cruel lies but they have touched my honour. Unworthy I am, but I am the son of Edward the Third and after you, my lord King, the greatest of peers of the realm. These malicious rumours which have been circulated about me if true – which God forbid – would amount to treason. My lord, until the truth were known I could do nothing. You will see that I stand to lose more by treachery than any man in England. Apart from this it would be a strange and marvellous thing if I should so far depart from the traditions of my blood. Let any man, whatever his degree, dare charge me with treason, disloyalty or any act which would bring harm to this kingdom and I will defend myself with my body.’

The members listened with amazement. It was an appealing scene, this great and magnificently attired man, kneeling to his nephew, a slender boy.

As he rose to his feet the members came forward. They were moved by their emotion. He must not go, they said. He must stay close to the King. They needed his skill and his experience.

No, replied John firmly. He needed time for reflection. He must show the country that his ambition was but to serve it.

There was protest against those who had maligned him. He smiled.

‘It pleases me, my lords,’ he said, ‘that you have at last recognised this for what it is.’

When Alice Perrers was brought to trial John did not attempt to defend her, and stood aside while the sentence which had been delivered by the Good Parliament was confirmed.

It seemed indeed that John of Gaunt had either forgotten his ambitions or had never had them, and had just managed to incur the dislike of the people who had invented tales about him such as the one of his birth which had proved to be quite absurd.

He will stay and become an adviser of his nephew, was the opinion. He is deeply hurt by the slanders which have been circulating and wants an assurance that we believe in his good faith.

In the palace of the Savoy John talked over his future with Catherine.

‘How would you like it,’ he asked, ‘if we were to retire to Kenilworth and live there in peace and quiet for a while?’

She stared at him incredulously.

‘You cannot mean that!’

‘I am considering it,’ he said. ‘You and I and the children … I could be a country gentleman … for a while.’

Catherine’s face betrayed her joy. Then she was sceptical.

‘But you would not! You could not …’

‘Aye, I could. I like to see my little Beauforts growing up. I shall like to think what I can do for them. And there are the others too.’

‘What has come over you? You could not leave this scene. It is your life. And you are nominated one of the King’s advisers.’

‘They are friendly now … At least Parliament is, but my enemies are there. The people are enamoured of a pretty boy. They love him dearly … and they may well continue to while he is a pretty boy. And the wicked uncle … How they hate the wicked uncle, Catherine! They tried to burn down his palace. Do you remember?’

‘I shall never forget it,’ she said with a shudder.

‘Yes … I have a new role to play: the injured uncle, the honest man who will do nothing until his honour has been proved. It is a new part for me, Catherine. Not an easy one to play, but methinks I shall play it better in the country … away from Court. Say … Kenilworth … Leicester or another of the estates. We shall live together you and I … as the good squire and his lady. How like you that?’

She threw herself into his arms. ‘Oh my lord, methinks I shall be the happiest woman in England.’

Richard was growing up quickly and learning that it was not all glory being a king. People did not remain enchanted for ever with their ruler simply because he was possessed of appealing youth and a handsome face.

For as long as possible the news of Edward’s death had been kept from the French who would most certainly see that their old enemy had become somewhat vulnerable. The old King even when he was becoming senile and the slave of his lust was still the old warrior; his image could only die with him. But now he was dead and there was a young boy on the throne, and the truce between the two countries was coming to an end.

They were not long in showing their intentions. Fleets from France and Castile came to the very shores of England. The Isle of Wight was overrun and pillaged; they even got as far as Gravesend and the smoke of the burning town could be seen from the City of London.

It could never have happened in the old King’s day, said the people.

Richard was depressed. It was not what he had looked for from kingship.

It was not to be expected that John of Gaunt would be content with the quiet life for long. A subsidy was raised for carrying on the war in France and John of Gaunt returned to public life and began to prepare a fleet for action.

He was at the coast while the ships were being made ready and Catherine was with him.

They rode out together; they inspected the ships together; he behaved with her as though she were his legal wife.

The people were aghast. Men in such positions might keep their mistresses – in fact they almost always did – but they were expected to behave with discretion. Yet John of Gaunt snapped his fingers at convention. It was as though he was telling them that he was too important to observe general rules. He did not care that they knew he had married his neglected wife for ambition. He wished to honour Catherine Swynford and so must they.

They resented this; especially as they were expected to pay taxes to help him regain the throne of Castile. He even called himself King of Castile, which was a constant reminder of his cynical approach to marriage. His poor wife was neglected and it seemed suffering from some indisposition which prevented her from bearing children. She had only one daughter, while Catherine Swynford had four bastards, all of whom were treated as though they were royal.

Who is she? they demanded of each other. No better than we are! And there she is riding out like a Duchess!

They did not actively abuse her. They were afraid of the French and the recent raids had startled them. They hoped that John of Gaunt would take his fleet across the seas and rid them of this much-feared enemy.

Any small popularity he might have gained by his behaviour at the coronation and immediately afterwards was lost when part of the fleet was defeated by the Spaniards and the rest came home having completely failed to achieve its purpose.

Then another incident occurred which set the people murmuring against him once again.

There were two squires, Robert Hauley and John Shakyl, who had leaped into prominence after the battle of Nájara. These two had captured an important nobleman, the Count of Denia, and, after the custom of the day, hoped to make a handsome sum from the adventure. It was, after all, one of the reasons why so many knights went to war and one of the most valuable perquisites of battle was what could be obtained from ransoms. And naturally the higher the rank of the captive, the greater the reward to be expected …

The Count had been released when his son was delivered to the two squires as a hostage; and as all that had happened ten years ago, the boy had now become a young man while the Count was still trying to raise the ransom money.

That autumn a representative of the Count had come to England with part of the ransom in the hope that this would be acceptable and his son released. The two squires, however, having kept their hostage for ten years were not going to accept less than their demand and they refused to parley with him.

It was at this point that the government stepped in and Hauley and Shakyl were ordered to surrender their hostage to the Council. After having waited ten years when they lived in expectation of a very large sum of money, the two squires, rather naturally, refused. As this was construed as contempt of the government and they were accused of making a private prison of their house, they were ordered to be sent to the Tower.

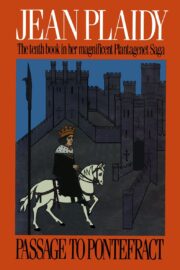

"Passage to Pontefract" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Passage to Pontefract". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Passage to Pontefract" друзьям в соцсетях.