‘Nonsense, my dear. John is delighted with one who is so good to me.’

‘My lord,’ said John, ‘I have much with which to occupy myself if I am to raise this army in good time. I pray you give me leave to go about my business.’

‘Go, John. Go. I expect to hear good news of you.’

As he left Alice’s laughter echoed in his ears.

How could a great man become a slave of his passion? he thought. It made him none the more easy in his mind because he could understand the King’s feeling for his siren.

The Black Prince was at Cognac awaiting John’s arrival. He was coming with a big force. Four hundred men at arms and four thousand archers should give them what they needed.

The Prince was fighting off one of those debilitating attacks of dysentery which were occurring with alarming frequency. Joan had been against his coming. ‘Leave it to others,’ she had said. ‘You have done your part. You have earned a rest.’ He could not heed her though. Battle was in his blood and he could see that if he was not there these possessions in France, so vital to England, could slip away.

The King of France was naturally taking advantage of the situation and must be rejoicing in the disability of the Black Prince.

But John would come with his army and they would stand together. He felt uneasy about John. He had always known of his brother’s ambition. He had now brought with him a commission that such places of Aquitaine which gave their allegiance to the King of England should be received into favour. He, John, would be the arbiter, in the absence of the Black Prince. Was John trying to take over Aquitaine from his brother?

No, it was reasonable enough. Edward was ailing. There were times when even in camp he was too weak to rise from his bed.

He must not be suspicious of his own brother; and yet the anxieties would not be entirely dismissed.

He felt old and ill and disillusioned. His life was battle. He had been bred to it; and since his father had laid claim to the throne of France he had been dedicated to that goal. He himself would one day be King of England and King of France. He must not forget that. And he must make those thrones safe for little Edward.

Thinking of his son gave him heart. As fine a boy as he had ever seen. Joan scolded him and said he spoilt his eldest son. She was always trying to push Richard forward. Richard was a good boy, it seemed, but he was not like his elder brother. Never mind. They would have a scholar in the family. It did not matter as long as they had the kingly Edward as the firstborn.

He was depressed nevertheless. He had heard only recently of the death of Sir John Chandos. Beloved friend of his childhood who had been close to him ever since. Chandos had saved his life at Poitiers and he had been rewarded with the manor of Kirkton in Lincolnshire, but nothing could be an adequate reward for what he had done. Chandos once said that he had the reward which meant most to him – the Prince’s lifelong friendship.

And now Chandos was dead – killed in battle. Edward mourned him deeply and could not forget him. He had died – this good friend – in his service, killed not far from Poitiers and buried at Mortemer.

To lose such a friend left a scar on his memory which would never heal.

And here he was, himself so sick that at times he thought his end was near.

It was a depressing outlook. He could only thank God for the devotion of Joan and the good health of his son.

As he lay in his tent, exhausted by the ride and determined not to take to his litter until it was absolutely necessary, news came to him that Jean de Cros, the Bishop of Limoges whom Edward had regarded as his friend, had surrendered the town to the French.

Limoges! To have let the French in. The man was a traitor. A raging fury possessed the Prince.

‘By God,’ he cried, ‘he shall suffer for this. Traitor that he is. Why should traitors such as this man live while great men like Chandos are cut down in the flower of their manhood?’

Never had any of his men seen him so overcome by fury.

‘Not a moment shall be lost,’ he cried. ‘We shall leave without delay for Limoges.’

Nor did his fury abate as he rode out with John of Gaunt beside him.

‘We shall have the town in a matter of days and then, by God, we shall see what happens to traitors.’

John was amazed by his brother’s fury. Towns had surrendered to the enemy before. Sometimes it was a wise thing to do if it could save bloodshed and destruction, and the Prince, who was not naturally a violent man, should understand this.

But on this occasion his anger persisted and it did not abate. All through the six-day siege he was like a man possessed with one motive in life – revenge on Limoges.

At length, the city could hold out no longer. The moment had come.

The Black Prince, hitherto famous for his chivalry towards a fallen enemy, screamed in his rage: ‘Let no one in that town live. Put them all to the sword.’

‘Women and children, my lord?’

‘All. All!’ screamed the Prince.

‘But, my lord …’

‘By God. Did you not hear me? Do your duty or it will be the worse for you.’

What had happened to this man, this noble Black Prince whose name was associated with all that was glorious in military matters?

He had changed. He was a tyrant. He called for blood. He wanted vengeance. The very name Limoges sent him white with fury.

The Bishop was captured.

‘Bring him to me,’ shouted the Prince. ‘I will show him what happens to traitors.’

His brother was beside him. ‘Edward … I would speak with you alone …’

He turned on John – this brother who had always sought honours, who had married Blanche of Lancaster, inherited her estates and become the richest man in England under the King.

John was humble now … appealing. ‘A word, Edward … just a word.’

They were alone in the tent.

‘Edward,’ said John, ‘we must have a care. This is a man of the Church. We could bring down the wrath of the Pope on us if harm befell him.’

‘You would plead for this traitor!’

‘Traitor he may be, but he is a Bishop. Edward, I beg of you. You have had your revenge on Limoges and I tell you this, it may well be in time that you will regret this act. But for the sake of England and our armies do not harm the Bishop.’

The Prince put his hand to his head. John took him by the arm and made him sit down.

‘You are sick, Edward,’ he said. ‘You are overwrought. I beg of you take care.’

The Prince was silent for a few moments. Then he said: ‘I pass the traitor Bishop over to you.’

John was greatly relieved.

The Bishop was made his prisoner.

The army encamped outside Limoges and the Black Prince stood watching the black smoke of the devastated town rising to the sky. He fancied he could hear the cries of murdered people as his men went from street to street carrying out his orders – not a man, woman or child to remain.

Now that he had shown everyone what it meant to defy the Black Prince, a calm had settled on him.

With it came the terrible realisation that he would hear the cries of the people of Limoges for the rest of his life.

They carried him in his litter. It was useless to attempt to sit his horse. He was sick and he had to face that fact.

They rested awhile at Cognac where he hoped he might recover sufficiently to continue with the army, but it was clear that this was not to be.

There was only one alternative. He must return to Bordeaux.

When he arrived Joan, horrified at his appearance, insisted that he stay in his bed; moreover she sent for the doctors and told them that she wanted to know the truth and why it was that her husband, hitherto so strong, had become a victim to this recurring sickness.

The verdict was that he had endured too many hardships on the battlefield over many years and that he should not return to such conditions until he was completely recovered.

‘My lady,’ they said, ‘he should return to England. There he should retire to the country and live quietly until his health is restored. It is our considered opinion that this is the only way to prevent his illness growing worse.’

That decided Joan. She would hear no protests.

‘My dear,’ said the Prince, ‘what will become of Aquitaine if I go home?’

‘My dear,’ she retorted, ‘you are worth a thousand Aquitaines.’

‘I am not sure that anyone else would agree with that.’

‘I have never greatly cared for the opinions of others. We are going home.’

She was delighted. It was what she had always wanted. She had made the Court of Aquitaine one of the most brilliant in Europe. Wandering musicians had always been well received at the castle; poets flourished there; it was delightful in the evening when the trestle tables had been cleared of food and taken away and songs of love and chivalry were sung.

But alas the Prince was so seldom there – he was always away winning some glorious battle which never seemed to bring the war any nearer to an end. How much better it would have been if he had remained at home.

Joan could have been happy in Bordeaux if it were not for this senseless fighting.

But even though she loved the climate which was softer than that of England and the fertile country with its colourful flowers, she had often felt a longing for her native land, and if she could go home and take her husband and her boys with her and have them completely under her care she would be happy.

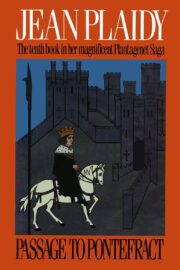

"Passage to Pontefract" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Passage to Pontefract". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Passage to Pontefract" друзьям в соцсетях.