‘Thank you,’ she said, hoping that her voice was steady, ‘but you have no need to repeat your offer. My refusal still stands.’

She saw Richard’s lips curve into a wicked smile. ‘And yet you kissed me as though you meant it. Several times, in fact…’

Deb met his gaze. This was a tricky statement to rebut since she was all too aware that she had succumbed to Richard’s skilful seduction with what could be considered a certain amount of enthusiasm. In fact, she had succumbed not once, but twice, so there was no possible way that she could dismiss it as an aberration.

She burned to think of their kisses. She had enjoyed being in Richard’s arms and wanted to be there again. Yet she remembered the comparison with eating the truffles. They seemed like such a good idea at the time. They were delicious, sinful, a wicked indulgence to which she knew she should not surrender. She was equally certain that she should not surrender to Richard. She gave him a cool smile.

‘Remember that I have consigned you to the same category as drinking too much wine, my lord,’ she said, ‘the category of being very, very bad for me.’ She spun away from him and turned towards the door. ‘Excuse me, I must go home. I am promised to drive along the river with Mr Lang this afternoon and do not wish to be late.’

Richard smiled easily. ‘My route takes me back the same way as yours. I will escort you.’

‘No thank you,’ Deb said. ‘I enjoy walking alone. Besides, you know full well that Mallow is not on the way to Kestrel Court.’

‘It could be,’ Richard said, smiling engagingly. ‘Besides, I feel that it would be safer for you to be accompanied.’

Deb arched her brows. ‘Having an escort may be safer in general but in this specific case I do not require your company.’

Richard laughed. ‘You are always refusing me.’

‘I am.’ Deb smiled sweetly. ‘That should tell you something, I believe.’ She called a hasty farewell to Ross and Olivia and slipped out into the hall, congratulating herself on her swift escape.

She had not gone more than a few paces before she heard Richard’s footsteps behind her and he caught her up as she reached the main door, putting a hand on her arm.

‘A moment, Mrs Stratton,’ he said. ‘You have left your book behind.’

Deb felt annoyed at her carelessness. She had hurried out, wishing to escape his troubling presence, but in doing so she had given him a genuine reason to follow her. Now she could hardly be uncivil as a result. She took the book of poetry and tucked it under her arm, reining in her exasperation as Richard held the door open for her and accompanied her down the steps and on to the gravel.

‘Thank you,’ she said, trying not to sound too grumpy. ‘There really is no need for you to escort me to Mallow, you know.’

Richard smiled and fell into step beside her. ‘No need other than to take pleasure in your company.’

Deb laughed. ‘Why do you persist where there is no hope, my lord?’

Richard gave her a very straight look. ‘Perhaps I am of stubborn disposition, like you yourself, madam.’

He held open the little white-painted gate that opened on to the path to Mallow and stood aside for her to precede him. To Deb’s surprise he made no attempt to engage her in teasing repartee and even less to force his attentions on her. They spoke politely enough on a number of topics, from the state of the roads to the current invasion threat and the political situation. To converse with Richard in an entirely natural manner proved dangerously enjoyable to Deb, for he was a most interesting man to talk with. Occasionally he would hold a gate open for her or pull aside a spray of briars from her path with exemplary courtesy. Deb found it disconcerting, not because she had imagined him without manners, but because it made her feel quite ridiculously cherished. She was rather annoyed with herself for being so receptive to his thoughtfulness, but she could not deny that the walk, in the late summer sunshine, was a very pleasant experience.

The path joined the lane to Midwinter Mallow and from there another white-painted wooden gate led into the back of Deb’s gardens at Mallow House. At the gate Deb paused, preparing to make her farewells and fidgeting a little with her book of poetry as she did so. She realised that she had pulled some of the binding loose and peered at it with dismay.

‘Oh dear, I-’ She stopped, staring. ‘Oh-but this is not my book!’

Richard came across to her. Deb opened the book and flicked through it. Now that she was looking closely, she could see that this book was exactly the same as the one he had given her, except that it was a little older and more worn. The list of odd symbols that she had tucked carelessly inside the front cover was also missing now. She searched the pages, the frown deepening on her brow.

‘Are you looking for this?’ Richard enquired affably. He put a hand inside his jacket and retrieved a folded paper. Deb stared from it to his face. He was watching her, but with neither the speculation nor the admiration to which she had become accustomed. There was an unreadable expression in his eyes and a hard line to his mouth and Deb felt a sudden chill. She put out a hand for the sheet, but he twitched it out of her grip.

‘Oh, no, Mrs Stratton,’ he said, his voice pleasant but definite. ‘It is scarcely that simple. I believe that you have some explaining to do.’

Chapter Eight

‘A re you saying that this is your property, Mrs Stratton?’ Richard was still holding the sheet of paper out of Deb’s reach and his intent gaze had not wavered from her face.

Deb looked at him, bewildered. ‘No,’ she said. ‘I found it in the book. How did you get hold of it?’

Richard ignored her question. ‘So you are claiming that neither the book nor the sheet of paper belongs to you?’ he asked.

His high-handed manner lit a flicker of temper in Deb. ‘I am not claiming anything,’ she said sharply. ‘I am telling you that that is not my book. You should know-you gave it to me yourself!’

Richard took the book from her hand and turned it over, scrutinising it. A shadow of a smile touched his mouth. ‘It is certainly not the copy that I gave to you, but that does not mean it is not yours,’ he said smoothly. ‘Presumably you had a copy that you were using before you received my gift?’

Deb glared at him. ‘I am not entirely sure of the purpose of your questions, Lord Richard,’ she said cuttingly, ‘nor by what right you are asking them-’ She broke off as a cart came around the corner of the road, its wheels churning the dust, harness jingling. Richard gave one sharp glance over his shoulder, caught her arm and bundled her unceremoniously through the wooden gate and into the shrubbery, along the mossy path and past the tangled ranks of holly and laurel.

Deb was taken aback at the manoeuvre. It was not that she suspected him of any sinister motive, rather that his sudden action had taken her by surprise. As soon as they were out of sight of the road he released her arm and Deb sank down on to the stone bench that had once had a very pretty view across to the river, until her garden had grown so out of hand that it was now hidden from sight.

Richard remained standing. In the pale sunlight that was filtered through the leaves Deb saw that he was watching her with narrowed gaze. She rubbed her arm automatically and gave him back a defiant look, but under her bodice her heart was beating rather quickly. Whatever this was about, it was no game. She could sense that instinctively.

‘I apologise for my actions just now,’ Richard said, immaculately polite. ‘I had no wish for us to be seen or overheard.’ He glanced around. ‘I take it that we are hidden from view here?’

Deb nodded. ‘No one can see us from the house or from the road.’ She looked at him. ‘I do not understand.’

Richard paused for a moment, then came to sit beside her on the bench. He sat forward, turning the sheet of symbols over in his hand.

‘Please, would you answer some questions for me?’ he asked.

Deb nodded silently, her eyes fixed on his.

‘Before I gave you a new copy of the poetry book, what were you using?’ Richard asked.

Deb frowned. ‘I shared Olivia’s copy before,’ she said. ‘I do not have a great deal of money to spend on books.’

Richard’s gaze searched her face. ‘Tell me what happened today at the reading group,’ he said.

Deb rubbed her forehead as she tried to remember. ‘We studied “The World” by Henry Vaughan,’ she said, ‘then, after we had finished, Lady Sally asked us to go into the conservatory to have a look at the copy of the watercolour book.’

‘Did you take your book of poetry with you?’

‘No,’ Deb said, wrinkling her brow as she marshalled her thoughts in order. ‘I put it down on the table in Lady Sally’s library and picked it up again as we were on our way out. Except…’ she met his eyes ‘…I must have picked up the wrong book. We had all left our copies there. There was quite a pile of them. We all have the same edition and the books must have become muddled.’

‘You all have the same edition,’ Richard repeated. He was smiling ruefully.

‘Yes.’ Deb looked enquiringly at him. ‘All five of us have this book.’ She tapped the cover. ‘Mine was the only new copy.’

Richard’s gaze was intent on her. ‘When did you know about this?’ he asked, gesturing to the paper with the symbols on it that was still in his hand.

‘I found it when we arrived back at Midwinter Marney Hall,’ Deb said. ‘I dropped the book and the paper fell out. It was folded over, as though it had been used as a bookmark.’

She saw Richard’s eyes narrow thoughtfully. ‘Had you ever seen it before?’ he asked.

‘No, never.’ Deb shifted on the bench, increasingly uncomfortable. ‘To what end do you question me like this, my lord? Please tell me.’

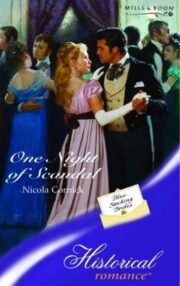

"One Night Of Scandal" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "One Night Of Scandal". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "One Night Of Scandal" друзьям в соцсетях.