"There were the French prisoners," she began. Her breath was coming in short gasps as she tried not to remember what had happened to them. "Because I was afraid. So afraid. Because I was a coward."

"Lily." He was still using the same voice. His eyes were looking very directly into hers, making it impossible for her to look away. He was her commanding officer again suddenly, not her husband. "It was rape. You were not a coward. It is a soldier's duty to survive any way he can in captivity—and you were a soldier's daughter and a soldier's wife. There is no question of cowardice. It was rape. It was not adultery. Adultery demands consent."

Neville sounded so certain, so sure of what he was saying. Could it possibly be true? She was not a coward? Not an adulteress?

"Let me hold you," he said softly. He was using a different voice now. "You look so very lonely, Lily."

A woman come home to a world that was alien to her and to a husband who had been about to marry someone else. How abject was it possible to feel? Would she never have herself back again, the serene, confident, happy self she remembered, the self who had somehow got lost after her one night of love?

She hunched her shoulders and looked down at her hands. When he came to stand in front of her and took her upper arms in his hands and drew her against him, she relaxed for a while, turning her head to rest against his shoulder, feeling the warmth and the strength of him all along her body. She allowed herself the luxury of feeling safe, of feeling cherished, of feeling that she had come home. He smelled good—of musk and soap and pure masculinity.

Yet she felt like someone who has arrived at the end of the rainbow only to find that there is nothing there after all—no pot of gold, not even the shreds of the rainbow itself. Just… nothing. And no more faith in rainbows. Only the core of herself with which to build a new identity, a new life.

She drew back from him before she could get lost in a dependency that would just not do.

"It would have been better for us both," she said, "if I had died."

"No, Lily." He spoke sharply.

"Can you tell me," she asked him, "that it has not once crossed your mind in the past year and a half that it was better so?"

She paused only briefly, but it did not escape her notice that he did not rush in with any denial.

"I think," she said, "if I had lived—if you had known I lived—you would not have brought me here. You would have found some excuse to keep me far away. You would have been kind about it. You would have explained that it was for my own good, and you would have been right. But you would not have brought me here."

"Lily." He had walked to one of the windows and was standing staring out into the darkness. "You cannot know that. I cannot know it. I do not know what would have happened. You were my wife. You were—dear to me."

Ah, she was dear to him. Not the love of his heart he had called her that night? Lily smiled bleakly and sat on the side of the bed, her arms hugging herself against the chill of the evening.

"I believe," she said, "this is an impossibility. To say I am out of place here is so obvious that it is laughable. She is not out of place, is she? Lauren? She has been brought up to all this and to being your wife and your countess. Instead she has been made miserable, your future is in ruins, and I… Well."

"Lily." He had come back to her, stooped down on his haunches before her, and taken both her hands in his. "Nothing is impossible. Listen to yourself. Is this Lily Doyle speaking? Lily Doyle, who marched the length and breadth of the Peninsula, undaunted by the heat of summer, the bitter cold of winter, the dangers of battle and ambush, the discomforts and diseases of camp? Lily Doyle, who always had a smile and a cheerful word for everyone? Who saw beauty in the dreariest surroundings? There is nothing impossible that you of all people cannot make possible. And I will help you. We freely joined our lives together on that hillside in Portugal. We must soldier on, Lily. We have no alternative. I am not sure I would even wish for one."

She did not know if she could resurrect that old Lily. But she warmed to his faith in her.

"Perhaps," she said, smiling wanly, "I am just tired and dispirited. Perhaps everything will look brighter in the morning. It has been a difficult day for both of us. Thank you for your kindness. You really have been kind."

"You would rather be alone?" he asked her. "I will stay and hold you through the night if you need the comfort, Lily. I will not press other attentions on you."

It was tempting. It would be so very easy to relax permanently into his kindness and his strength and become as abject in a way as she had been with Manuel. But somehow if she was going to find a way to cope with this new, frightening, impossible life, she must not give in to a need for the comfort of his arms—especially when she did not want more than that from him.

"I would rather be alone," she said.

He squeezed her hands before releasing them and getting to his feet. "Good night, then," he said. "If you should need me, tonight or any other night, my dressing room adjoins yours and my bedchamber is beyond that. If you need anything else, the bell pull is beside your bed. Your maid will answer it."

"Thank you," she said. "Good night."

She wondered suddenly how his intended bride—Lauren—was feeling tonight. Did she love him? Lily felt genuinely sorry for her, caught in a situation in which she was entirely innocent and totally helpless. This was to have been her wedding night, but Lily was in the countess's room instead of her.

Everything was so very wrong.

Chapter 8

Manuel was on top of her while she lay beneath him, and then she opened her eyes to see him—Major Newbury, Neville—standing in the doorway of the hut, watching. There was that look on his face that she had seen there sometimes immediately after battle, a hard, cold, battle-mad, almost inhuman look, and his white-knuckled hand was on the hilt of his sword. He was about to kill Manuel and rescue her. Hope soared painfully as she tried to lie still so as not to alert Manuel.

The dream always proceeded the same way. After standing there, white-faced and immobile for endless moments, he turned away and disappeared, and precious minutes were lost to her while Manuel took his pleasure of her.

In the dream she was free to run after Neville as soon as Manuel was finished with her, but her legs were always too weak to carry her at any speed and the air was too thick to move through. She had no voice with which to call to him, and she could never see where he had gone, which direction he had taken. There was always mist swirling about and panic immobilizing her. And then—the crudest part of the dream—the mist suddenly cleared and there he was, only a few steps away, standing still, his back to her.

In the dream she always stopped too at that moment, afraid to proceed, afraid to reach out to him, afraid of what would be in his eyes if he turned. It was the most dreaded moment of the dream and almost its final moment, when she touched the terrifying depths of despair. For during that second of indecision, the mist swirled again and he disappeared, not to be seen again.

She dreamed the nightmare twice during the first night at Newbury Abbey.

She rose when it was still dark, made up her bed, washed in cold water in the dressing room, and clothed herself in her old blue cotton dress. She had to get outside where she could breathe. She did not stop to pick up a bonnet or to pull on her old shoes. She had to feel the good earth beneath her feet. She had to feel the air against her face and in her hair. She met no one on her way downstairs or while she did battle with the heavy bolts on the front doors.

Eventually she was outside, where there was the merest suggestion of dawn in the eastern sky. She breathed in deep lungfuls of chilly air. She felt it raise goosebumps on her bare arms and begin to numb her feet. She was immediately calmed and set out for the beach.

She did not stop until she was at the water's edge. At the edge of the land, the edge of place and time. On the brink of infinity and eternity. The wind, blowing off the vast expanses of the unknown, was strong and salt and chill. It flattened her dress against her and sent her hair billowing out behind her. Her feet sank a little into spongy sand. Above her gulls wheeled and cried, like spirits already free of time and space. For a moment she envied them.

But only for a moment. She felt no real desire this morning to escape the bonds of her mortality. Her years with the army had taught her something about the infinite preciousness of the present moment. Life was such an uncertain, such a fleeting thing, so filled with troubles and horrors and miseries—and with wonder and beauty and mystery. Like all persons, she had known her share of troubles. An almost overwhelming abundance of them had begun for her just the day following both the unhappiest and happiest day of her life, when her father had died and Major Newbury had married her. But she had survived.

She had survived!

And now—now at this most precious of moments—she was free and surrounded by such elemental beauty that her chest and her throat ached with the pain of it all. And it seemed to her that the wind blew through her rather than around her, filling her with all the mysterious spirit of life itself.

How could she fail to reach out and accept such a gift?

How could she fail to let go of the suffocating shreds of her dream and of all the misgivings about her new life that had oppressed her yesterday?

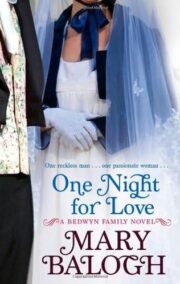

"One Night for Love" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "One Night for Love". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "One Night for Love" друзьям в соцсетях.