"Perhaps," Neville had said with quiet emphasis, "you would care to remember, Wilma, that you are speaking of my wife."

She had tutted, but she had said no more.

His mother had got to her feet to leave the room. "I must return to the dower house and see what is to be done for poor Lauren," she had said. "But tomorrow I shall move back into the abbey, Neville. It is going to need a mistress, and clearly Lily will be quite unable to assume that role for some time to come. I shall undertake her training."

"We will discuss the matter some other time, Mama," he had said, "though I agree it would be best if you moved back here. I will not have Lily made unhappy, however. This is all very difficult for her. Far more difficult than for any of us."

He had left the room before anyone could say anything more and had come to stand on the steps. There were some days, he reflected, that were so unremarkable that a week afterward one could not recall a single thing that had happened in them. And then there were days that seemed packed full of a lifetime of experiences. This was definitely one such day.

He had written several letters after returning from the dower house and then checking on Lily, who had been fast asleep. He had sent the letters on their way. It would not be easy to be patient in awaiting the replies.

The fact was that for all his solicitude, for all his apparent calm, he simply was not sure Lily really was his wife.

They had married without a license and without the customary banns. The regimental chaplain had assured him that the wedding was quite legal, and he had drawn up the proper papers to which Neville had put his signature and Lily her mark and which had been witnessed by Harris and Rieder. But Parker-Rowe had been killed in that ambush the following day. Harris had reported that the belongings of the dead had been left with them in the pass.

That would seem to mean that the marriage had never been registered. Was it therefore not a marriage at all? Was it void? Neville supposed that his mind must have touched upon the possibility before today. But he had never pursued the question. It had been unimportant. Lily had been dead.

But now she was alive and at Newbury Abbey. He had acknowledged her as his wife and his countess. Lauren had been made to suffer. All their lives had been turned upside down. But perhaps there was no legality to the marriage. He had written to Harris—now Captain Harris, it seemed—and to several civil and ecclesiastical authorities to try to find out.

What if he and Lily were not legally married after all?

Should he mention his doubts to her now before he knew the answer? Should he mention them to anyone else? The question had been weighing on his mind ever since it had struck him as he stood on the beach with her, gazing out across the sea. But he had decided to keep his doubts to himself until he had the answer. He was not sure it would make a great deal of difference anyway. He had married Lily in good faith. He had made vows to her that he had had every intention of keeping. He had consummated the marriage with her.

And he had loved her.

But he could not rid his mind of the image of Lauren, swinging gently back and forth on the tree swing in her wedding gown, listless and quietly accepting of her disappointment—and surely about to explode with the anger she had told him was pointless. A bride rejected and humiliated.

This was the devil of a coil, he thought. He felt weighed down by guilt even though common sense told him that he could not possibly have foreseen the day's events.

***

Lily was thankful to be out of doors again—away from that great daunting mansion and the bewildering crowds of people.

Elizabeth had suggested a stroll to the rock garden, which was strangely named as it had far more flowers and ornamental trees than rocks. Graveled walkways meandered through it and a few well-placed wrought-iron seats allowed the stroller to sit and appreciate the cultivated beauty. Lily was more accustomed to wild beauty, but a garden lovingly created and tended by gardeners had its charm, she decided.

Elizabeth walked with her arm drawn through the Duke of Portfrey's. Lily had to be told his name again, but she had noticed him in the drawing room, partly because he was a very distinguished-looking gentleman. She guessed his age to be about forty, but he was still handsome. He was not very tall, but his slim, proud bearing made him appear taller than he was. He had prominent, aristocratic features and dark hair, which had turned silver at the temples. Mainly, though, she had noticed him because he had watched her more intently than anyone else had. He had scarcely taken his eyes off her, in fact. There had been a strange expression on his face—almost of puzzlement.

He asked some pointed questions as they walked.

"Who was your father, Lily?" he asked.

"Sergeant Thomas Doyle of the Ninety-fifth, sir," she told him.

"And where did he live before he took the king's shilling?" he asked.

"I think Leicestershire, sir."

"Ah," he said. "And where exactly in Leicestershire?"

"I do not know, sir." Papa had never talked a great deal about his past. Something he had once said, though, had led Lily to believe that he had left home and joined the army because he had been unhappy.

"And his family?" the duke asked. "What do you know of them?"

"Very little, sir," she replied. "Papa had a father and a brother, I believe."

"But you never visited them?"

"No, sir." She shook her head.

"And your mother," he asked her. "Who was she?"

"Her name was Beatrice, sir," she said. "She died in India when I was seven years old. She had a fever."

"And her maiden name, Lily?"

Elizabeth laughed. "Are you planning to write a biography, Lyndon?" she asked. "Pray do not feel obliged to answer, Lily. We are all curious about you because you have suddenly been presented to us as Neville's wife and your life has been so fascinatingly different from our own. You must forgive us if we seem almost ill-bred in our inquisitiveness."

The duke asked no more questions, Lily was relieved to discover. She found his blue eyes rather disconcerting. He gave the impression of being able to see right into another person's mind.

"Do you know the names of all these flowers?" she asked Elizabeth. "They are very lovely. But they are different from flowers I know."

They sat on one of the seats while Elizabeth named every flower and tree and Lily set herself to memorizing their names—lupins, hollyhocks, wallflowers, lilies, irises, sweet briar, lilacs, cherry trees, pear trees. Would she ever remember them all? The Duke of Portfrey strolled along the paths while they talked, though he did pause for a while at the lower end of the rock garden to gaze back at Lily.

***

Lady Elizabeth stood beside the fountain watching Lily return to the house. She looked small and rather lost, but she had declined Elizabeth's offer to accompany her to her room. She thought she could remember the way, she had said.

"She has courage," Elizabeth said more to herself than to the Duke of Portfrey, who was standing behind her.

"I must thank you, Elizabeth," he said stiffly. "for pointing out how ill-bred and excessively inquisitive my questions were."

She swung around to face him. "Oh, dear," she said, smiling ruefully, "I have offended you."

"Not at all." He made her a slight bow. "I am sure you were quite right."

"Poor child," she said. "One feels she is a child, though if Neville married her well over a year ago she cannot be so very young, can she? She is so small and looks so fragile, yet she has lived in India and Portugal and Spain with the armies. That cannot have been easy. And she was a captive of the French for almost a year. What is your particular interest in her?"

The duke lifted his brows. "Have you not just stated it?" he asked her. "She is a curiosity. And she has appeared at a moment that could not have been better chosen if it had been done for deliberate effect."

"But you surely do not believe that it was?" she said, laughing.

"Not at all." He was gazing broodingly at the door through which Lily had disappeared. "She is very beautiful. Even now. When Kilbourne has spent money on clothes and jewels for her and has brought her into fashion…" He did not complete the thought—he did not need to do so.

Elizabeth said nothing. She was never able to explain even to herself the nature of her relationship with the Duke of Portfrey. They had been friends for several years. There was an ease and a closeness between them that was rare for a single man and a single woman. And yet there was a distance too. Perhaps it was a distance that was inevitable when they were of different genders but were not also lovers.

Elizabeth had sometimes asked herself whether she would become his lover if he ever suggested it. But he never had. Neither had he asked her to be his wife. She was glad of that fact. Although she had lived through her youth and her twenties in the hope that she would meet a man for whom she could care enough to marry him, she was no longer sure she was willing to give up the independence she prized.

But sometimes she thought she would like the experience of being loved—physically loved—by the handsome Duke of Portfrey.

He had been married as a very young man—briefly and tragically. He had been a military officer at the time and a younger son who had not expected ever to succeed to his father's ducal title. He had married secretly before going off with his regiment, first to the Netherlands and then to the West Indies, leaving his bride behind and his marriage undisclosed. She had died before his return. Although it had been years and years ago, Elizabeth often felt that he had never quite recovered from the experience—never forgiven himself, perhaps, for leaving her, for not being with her when she died in a carriage accident, for not being there for her funeral.

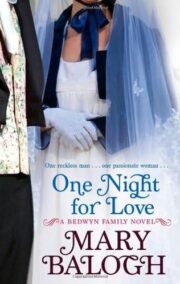

"One Night for Love" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "One Night for Love". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "One Night for Love" друзьям в соцсетях.