Lily looked at the developing style in the looking glass, her eyes wide with astonishment. "How extraordinarily clever you are," she said. "You have amazing skill, Dolly. I would not have thought it possible for my hair to look tame."

Dolly flushed with pleasure and pushed the final pin into place. She picked up a small hand mirror from the dressing table and held it up at various angles behind Lily so that she could see the back of her head and the sides.

"That will do for tea, my lady," she said. "For this evening we will need something more special. I will think of what to do. I hope your own maid does not arrive too soon, though I ought not to say so, ought I?" She was fluffing the short puffed sleeves of Lily's dress as she talked, watching the effect in the looking glass. "There you are, my lady. You are ready whenever his lordship comes."

It was not a comforting prospect. He was going to take her to tea. What did that mean exactly? But there was no time for reflection. Almost immediately there was a tap on one of the three doors of the dressing room and Dolly went to answer it—she seemed to know unerringly which one to open. Lily got to her feet.

He had changed out of his pale wedding clothes. He looked more familiar wearing a dark-green coat, though it was far more carefully tailored and form-fitting than his Rifleman's jacket had been. He looked her over quickly from head to toe and bowed to her.

"You are looking better," he said. "I trust you slept well?"

"Yes, thank you, sir," she said, and grimaced. She must remember not to call him that.

"You were fast asleep when I looked in on you earlier," he told her. "You are looking very pretty."

"Thanks to Dolly," she said, smiling at the maid. "She ironed my dress and tamed my hair. Was that not kind of her?"

"Indeed." He raised his eyebrows. "You may leave us… Dolly."

"Yes, my lord." The maid curtsied deeply without raising her eyes to him and scurried from the room.

Well, Lily could understand that reaction. She had seen soldiers leave his presence in similar fashion—though they had not curtsied, of course—after he had turned his eyes on them. His men had always worshiped him—and been terrified of his displeasure. Lily had never felt the terror.

"My name is Neville, Lily," he said. "You may use it, if you please. I am going to take you to the drawing room for tea. You must not mind. Several of my guests have already left so the numbers will not be quite overwhelming. They are mostly members of my family. I will stay close to you. Just be yourself."

But some of those grand people she had seen last night and this morning would be there, gathered in the drawing room? And he was going to take her there to join them? How could she possibly meet them? What would she say? Or do? And what would they think of her? Not very much, she guessed. She had lived most of her life with the army and was well aware of the huge gap that had separated the men—her father included—from the officers. And here she was, an earl's wife, making her first appearance at his home on the very day he was to have married someone else—a lady from his own class, she did not doubt. It would be difficult to imagine a less desirable situation.

But all her life Lily had been led into difficult situations, none of them of her own choosing. She had grown up with an army at war. She had adjusted to all sorts of places and situations and people. She had even lived through seven months of what many women would have considered a fate worse than death.

And so she stepped forward and took Neville's offered arm without showing any of her inward qualms, and they stepped out into the wide corridor she remembered from earlier. They descended one of the grand curved staircases. She looked down over the banister to the marble, tiled hall below and up to the gilded, windowed dome above. She had that feeling again of being dwarfed, overwhelmed.

"I expected a large cottage," she said.

"I beg your pardon?"

"Your home," she said. "I expected a large cottage in a large garden."

"Did you, Lily?" He looked gravely down at her. "And you found this instead? I am sorry."

"I thought only kings lived in houses like this," she said, and felt very foolish indeed, especially when his eyes crinkled at the corners and she realized she had said something to amuse him.

Then they were approaching two huge double doors and one of those liveried footmen waited to open them. He was the footman she'd encountered last evening, Lily saw. She could even remember what the superior servant had called him. Her life with the army had made her skilled in remembering faces and the names that went with them. She smiled warmly.

"How do you do, Mr. Jones?" she asked.

The footman looked startled, blushed noticeably beneath his white wig, bobbed his head, and opened the doors. Lily glanced upward to see that Neville's eyes were crinkled at the corners again. He was also pursing his lips to keep from laughing.

But she had no chance to consider the matter further because as soon as they stepped inside the drawing room, she was assaulted by so many impressions at once that she was struck quite dumb and breathless. There was the hugeness and magnificence of the room itself—four of her imagined cottages would surely have fit inside it with ease. But more daunting than the room was the number of people who occupied it. Was it possible that any of the wedding guests had already left for home? Everyone was dressed with somewhat less magnificence than either last evening or this morning, but even so Lily suddenly realized that her own prized muslin dress was quite ordinary and her wonderful coiffure very plain. Not to mention her shoes!

Neville took her, in the hush that followed their entrance, toward an older lady of regal bearing and attractively graying dark hair. She was seated, a delicate saucer in one hand, a cup in the other. She looked as if she had frozen in position. Her eyebrows were arched finely upward.

"Mama," Neville said, bowing to her, "may I present Lily, my wife? This is my mother, Lily, the Countess of Kilbourne." He drew breath audibly and spoke more quietly. "Pardon me—the dowager Countess of Kilbourne."

She was the lady who had stood up at the front of the church during the morning and spoken his name, Lily realized. She was his mother—she set down her cup and saucer and got to her feet. She was tall.

"Lily," she said, smiling, "welcome to Newbury Abbey, my dear, and to our family." And she took one of Lily's hands from her side and leaned forward to kiss her on the cheek.

Lily smelled a whiff of some expensive and exquisite perfume. "I am pleased to meet you," she said, not at all sure that either of them spoke with any degree of sincerity.

"Let me present you to everyone else, Lily," Neville said. The room was remarkably silent. "Or perhaps not. It might prove too overwhelming for you. Perhaps a general introduction for now?" He turned and smiled about him.

But the dowager countess had other ideas and told him so. "Of course Lily must be presented to everyone, Neville," she said, drawing Lily's arm through her own. "She is your countess. Come, Lily, and meet our family and friends."

There followed a bewildering spell that felt hours long to Lily though it was doubtful it exceeded a quarter of an hour. She was presented to the silver-haired gentleman and the lady with all the rings she had seen downstairs last evening and understood that they were the Duke and Duchess of Anburey, the dowager countess's brother and sister-in-law. She was presented to their son, the Marquess of something impossibly long. And then she was aware only of faces, all of which belonged to persons with first names and last names and—all too often—titles too. Some were aunts or uncles. Some were cousins—either first or second or at some remove. Some were family friends or her husband's particular friends or someone else's friends. Some of them inclined their heads to her. Several of the younger people bowed or curtsied to her. Most smiled; some did not. All too many of them spoke to her; she could think of nothing to say in reply except that she was pleased to meet them all.

"Poor Lily. You look thoroughly bewildered," the lady behind the tea tray said when Lily and the dowager countess finally reached her. "Enough for now, Clara. Come and sit on this empty chair, Lily, and have a cup of tea and a sandwich. I am Elizabeth. I daresay you did not hear it the first time, and really it does not matter if you forget it the next time you see me. We have only one name to remember while you have a whole host. Eventually you will sort us all out. Here, my dear."

She had been pouring a cup of tea as she spoke and handed it to Lily now with a plate of tiny sandwiches with the crusts cut off. Lily was not hungry, but she did not want to refuse. She took a sandwich and then discovered that if she was to drink, as she dearly wished to do, she must eat the sandwich first so that she might have a hand free with which to lift the cup. The china was so very delicate and pretty that she felt a sudden terror of dropping some of it and smashing it.

Neville's hand came to rest on her shoulder.

The room was no longer silent, Lily noticed in some relief, and all attention was no longer focused on her. Everyone was being polite, she gathered. She listened to the conversation that flowed around her as she ate her sandwich and succeeded in sipping her tea without mishap. But she was not being ignored either. People whose names she could not remember—what a time for her usual skill of memory to have deserted her!—kept trying to draw her into the conversation. A few of the ladies had been having a spirited discussion on the relative merits of two types of bonnet.

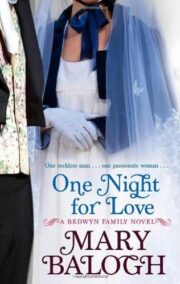

"One Night for Love" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "One Night for Love". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "One Night for Love" друзьям в соцсетях.