Spurred on by Henry’s confrontation with her father, Ellie had also taken her life into her own hands. She accepted a place at the Edinburgh School of Art to pursue a course in design, funding herself by selling some of the jewellery her mother had left her. ‘I only sold the ugly pieces,’ she told Cat. ‘Big stones in clumsy settings. I’ve kept the antiques. But my father really does have dreadful taste in jewellery. I’m not sorry to see the back of most of it.’ Of her romantic life, she never spoke, perhaps with good reason.

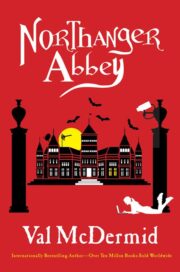

Ellie and Cat had continued with their children’s book project. They’d collected a raft of rejections, but finally an indie publisher in Edinburgh had bought the first two books in a series of comedy vampire stories. ‘Because of our family experience,’ Ellie had said with a giggle when they finally met their editor. Cat kicked her under the table. Not everyone could be expected to share their sense of humour.

Freddie’s tour of duty in Afghanistan being over, he had resigned his commission and taken up a lucrative position with an armament company. He was unable to attend the wedding because of a sales trip to a Gulf emirate. Nobody minded.

James Morland had carved out a niche in immigration and human rights law in his chambers in York. He’d fallen in love with one of his clients, a Somali woman who had just opened a restaurant near the university that was already winning rave reviews. James had gained both happiness and half a stone in the process.

Bella Thorpe had featured briefly in a reality TV show but had been eliminated in the first public vote of the season. Her brother Johnny had been fired by his bank after a series of dubious transactions came to light. Susie Allen took great delight in reporting their misfortunes to the Morlands, and even the vicar could not avoid the sin of schadenfreude.

And what of General Tilney? His first reaction to the rebellion of his younger children was to cut off their allowances and bar them from Northanger Abbey. His capacity for cutting off his nose was remarkable, but he had reckoned without the compassion their mother had installed in Henry and Ellie. A year after the terrible night when he had cast Cat out of the abbey, his younger son arrived there, having colluded with Mrs Calman to ensure the General was home alone.

Henry never revealed what had passed between them, but although there was never much subsequent warmth between father and son, neither was there the bitterness there had been previously. Ellie too had been welcomed back into the fold; now she had completed her degree, she was to take up residence at Woodston, where her father had promised to build a studio at the water’s edge.

The moral or message of this story is hard to discern. And that is as it should be, for as Catherine Morland found out to her cost, it is not the function of fiction to offer lessons in life.

"Northanger Abbey" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Northanger Abbey". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Northanger Abbey" друзьям в соцсетях.