Her seat was halfway up the coach, by the window. Her hopes of being left alone to wallow in her misery were dashed when a black youth around her own age dropped into the seat next to her. ‘All right, pet?’ he greeted her. She gave him a pained smile and he laughed. ‘Don’t look so worried, I’m not going to bother you.’ He plugged in his earphones and took a tablet computer out of his backpack. Inside a minute he was lost in a world of his own.

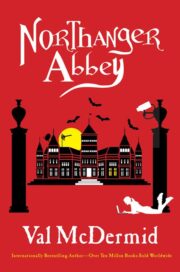

Cat was grateful for his disengagement. Seven and a half hours of being dragged into someone else’s concerns would have left her feeling even more murderous towards General Tilney, hard though that might be to credit. The journey itself had no terrors for her. She had plenty to think about and plenty of Hebridean Harpies to amuse her on her e-reader. The hard part was dragging her mind clear of Northanger Abbey.

She glanced at her watch. On the other side of the country, Henry would be sitting in the dining room at Woodston with his morning coffee and his bowl of cereal. She couldn’t believe he knew anything of what had happened, for he would surely have been in touch. Which reminded her, she hadn’t checked her phone to see if there were any messages. Not to mention the necessity of letting her parents know she was on her way home.

Cat rummaged in her daypack and fished out her phone. She thumbed the button to wake it up and nothing happened. She repeated her action, with no result. She pressed the power button but again there was no response. Realising the extent of her misfortune, Cat groaned out loud. She’d run the battery down during their car journey back from Woodston and she’d forgotten to charge it up again; the lack of signal at Northanger had broken her regular habit of plugging it in every night. And the charger was in her big bag, which was in the luggage locker somewhere under the coach. She was trapped in her isolation, unable to vent her feelings to anyone but herself.

The dead phone reminded her of how buoyant she’d felt on the journey back from Woodston. She’d posted photos of the house and the loch views to her Facebook page and tweeted her delight to the world. She’d even emailed a few pics to her parents, to let them see what a great time she was having. It had been a magical day. In spite of her terrible gaffe at Northanger, Henry was clearly pleased to see her and eager to spirit her off on her own. She couldn’t have wished for a better reaction to Bella’s ridiculous email. And he’d cared enough to ask about her future, as if it might concern him. She didn’t think she was imagining the undercurrent of affection that was building between them. This hollow feeling in her stomach when she thought of him was, she believed, a barometer of love.

And that day at Woodston, the General had been as genial as she’d ever seen him. Even Ellie had commented on his high opinion of her. So what could have happened to throw the switch from regard to contempt – for only contempt could have led to her abrupt dismissal. Surely Henry hadn’t told him about her night-time prowling and embarrassing suspicions? She couldn’t believe that of Henry, for what positive motive could he possibly have harboured for such a revelation? It wasn’t as if it was the sort of thing you could make a joke about – ‘Hey, Dad, Cat thinks you murdered my mother. Did you ever hear anything so funny?’ No, that one wouldn’t work, not even on the Fringe.

What would Henry think when he turned up at Northanger tomorrow evening to find them all gone? She was sure one of the Calmans would bring him up to speed. The question was whether they knew the true reason she’d been banished, which was more than she did herself. Cat wondered what they’d been told, because their behaviour had been at odds. Calman could not have been colder, while Mrs Calman, although she had said nothing, had provided her with enough food for a long weekend. So how would Henry react? Would he, like Ellie, acquiesce without protest in his father’s actions? Or would he be filled with regret and resentment? Would he be sufficiently moved to stand up to his father?

She doubted this last point. It was, she knew, hard to break the habit of a lifetime. And the General had so drilled his younger children in obedience that they struggled even to doubt his certainties. No, Henry would let her go. It was over before it had started. Over before he’d even kissed her properly – social air-kissing didn’t count, obviously.

Cat was so bound up in her thoughts and regrets that she barely noticed the passing of time or landscape. She almost welcomed the length and tedium of the journey, for once she had completed the second stage, another four hours on the coach from Victoria to Dorchester, she would be plunged into the necessity of explaining her precipitate return to her family and friends.

Although she longed to be back in their company after a month’s absence, Cat had no relish for an explanation that could only reflect badly on her. Even though she knew herself to be blameless, her mother and father, like all parents, would inevitably suspect their child had committed some sin so heinous or shaming she dared not admit to it. They might not go so far as to voice their views, but she knew that’s what they’d be thinking.

At that point, she was so depressed that she started on the sandwiches. Her last taste of Northanger, she thought as she bit into the rare roast beef, horseradish and lamb’s lettuce roll. Cat closed her eyes and savoured it. At least there were still some simple pleasures left to her.

* * *

Seven hours and fifty-three minutes after they’d left Newcastle, they pulled into the grimy terminal at Victoria. The exhaust-laden fumes were a shock to Cat’s lungs after the clear Borders atmosphere and the air-conditioning of the coach. She collected her bag and found the stand where the Dorchester service would leave from.

There were fewer travellers heading west that afternoon, so she had a double seat to herself. As they headed into the evening sun and the landscape grew increasingly familiar, Cat began to feel nostalgic for home. She’d dreamed of a very different return, the sort of triumph that featured in so many of the fictions she loved. She’d imagined Henry driving her back from Northanger; introducing him to the family; walking through the orchard to the Allens’ house, where he would declare undying love on the banks of the river. But her dreams were shattered now, revealed for the foolishness they had always been.

At least she’d been able to charge up her phone on this coach. But now that it was possible to text or phone home, Cat found herself increasingly reluctant to do so. Eventually, when they were less than an hour from Dorchester and the sun was starting to sink in the distance, she composed the necessary text.

On coach 2 Dorch. Due 9.17. Can u pick me up pse? Cat x

She despatched it to her father, and within five minutes the reply came.

??? Of course I can. Are you OK? Dad

How could she even begin to answer that question?

I’m OK. Fone ws dead b4. Looking 4ward 2 seeing u. Mist u all. C u soon. X

She could imagine them all, agog in the kitchen, wondering what on earth had brought her back so abruptly. They wouldn’t understand, any more than she had.

When she stepped off the coach at Dorchester, the sight of her father was almost more than she could bear. Cat threw herself into his hug, a bittersweet mixture of joy and pain twisting her heart. Now she was finally where she knew she was unconditionally loved, she could let go. Tears dripped down her cheeks as her father gently patted her back, bemused but professionally accustomed to offering comfort.

When Cat could at last let go, Mr Morland slung an arm round her shoulders and picked up her bag. ‘You don’t have to say anything now unless you want to get it off your chest before we get home,’ he said. ‘Otherwise, wait so you don’t have to go through it all twice.’

Cat swallowed and nodded. ‘OK. I love you, Dad.’

‘I know,’ he said. ‘And we love you too. No matter what. You know that.’

The last few miles of the journey were the hardest. But by the time they arrived at the vicarage, Cat had herself under control so that when they pulled up in the drive and her mother and sisters fell upon her with delight, she was able to contain her tears and enjoy the pleasure of being back in the bosom of a loving family again, rather than one that was ruled by a heartless tyrant.

Her mother bustled around the kitchen, heating soup and opening tins of baking while her sisters quizzed her about the excitements of Edinburgh and the shocking behaviour of Bella Thorpe. Eventually, though, those subjects were temporarily exhausted and Richard Morland shooed his younger daughters upstairs, citing the lateness of the hour.

Then at last, Cat was able to tell her story. She could tell from the looks her parents exchanged that they were shocked by a father who would throw a young woman out of doors with no notice to travel the length and breadth of the country alone. ‘And all this was decided in the middle of the night?’ Annie said, indignant.

‘It was after midnight when Ellie told me.’

‘I can hardly credit it,’ Richard said. ‘At the very least he should have phoned us to let us know Cat was on her way home. We could have been out, or away.’

Cat managed a feeble giggle. ‘You’re never away.’

‘Yes, but General Tilney wasn’t to know that. I’m astonished. Susie Allen spoke so highly of him. And you’ve no idea what provoked this?’

‘No idea at all. Truly, Dad, I’m not trying to cover up anything I did wrong. He seemed to quite like me. Ellie said he thought I was the bee’s knees. And then he just turned.’

"Northanger Abbey" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Northanger Abbey". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Northanger Abbey" друзьям в соцсетях.