He’d threatened to keep her prisoner, like some monster.

Which of them was the monster?

Good Lord, he was enormous.

And intimidating, somehow, despite being unconscious.

And handsome, though not in a classical way.

He was all size and force, even motionless. Her gaze tracked the length of him, the long arms and legs in perfectly tailored clothes, the cords of his neck peeking out from above the uncravatted collar of his shirt, the stretch of bronze to his strong jaw and dimpled chin, and the scars.

Even with the scars, the angles of his face betrayed his aristocratic lineage, all sharp edges and long slopes—the kind that set women to swooning.

Mara couldn’t entirely blame them for swooning.

She’d nearly swooned herself, once.

Not nearly. Had.

When he was young, he’d been quick to smile, baring straight white teeth and an expression that promised more than pleasantry. That promised pleasure. His size, combined with that ease, had been so calm, so unpracticed that she’d thought him anything but the aristocracy. A stable boy. Or a footman. Or perhaps a member of the gentry, invited by her father to the enormous wedding that would make his daughter a duchess.

He’d looked like someone who did not have to worry about appearances.

It hadn’t occurred to her that the heir to one of the most powerful dukedoms in the country would be the most carefree gentleman for miles. Of course, it should have. She should have known the moment that they came together in that cold garden and he smiled at her as though she were the only woman in Britain and he the only man, that he was an aristocrat.

But she hadn’t.

And she certainly hadn’t imagined that he was the Marquess of Chapin. The heir to the dukedom to which she would soon become duchess. Her future stepson.

The man sprawled across mahogany and carpet didn’t look anything stepson-like.

But she would not think on that.

She crouched low to check his breathing, taking no small amount of relief in the way his wide chest rose and fell beneath his jacket in even strokes. Her heart pounded, no doubt in fear—after all, if he were to wake, he would not be happy.

She gave a little huff of laughter at the thought.

Happy was not the word.

He would not be human.

And then, with the giddiness of panic coursing through her, she did something she never would have imagined doing. Or, rather, she would have imagined doing, but never would have found the courage to do.

She touched him.

Her hand was moving before she could stop it. Before she really even knew what she was about. But then her fingers were on his skin—smooth and warm and alive. And ever so tempting.

Her fingers traced the angles of his face, finding the smooth ridges of the inch-long white scar along the bone at the base of his left eye, then down the barely-there bumps and angles of his once-perfect nose, her chest tightening as she considered the battles that would have produced the breaks. The pain of them.

The life he’d lived to wear them.

The life she’d given him.

“What happened to you?” The question came out on a whisper.

He did not answer, and her touch slid to his final scar, at the curve of his lower lip.

She knew she shouldn’t . . . that it wouldn’t do . . . but then her fingers were on that thin white line, barely there against rich skin, edging into the soft swell of his lip. And then she was touching his mouth, tracing the dips and curves of it, marveling at its softness.

Remembering the way it had felt on hers.

Wishing for—

No.

Her hand came away from him as though she’d been burned, and she turned her attention to the rest of him, to the way one arm spread haphazardly across the carpet, the victim of laudanum. He looked uncomfortable, and so she reached across him, intending to straighten that arm, to lay it flat against his side. But once his hand was in hers, she couldn’t help but consider it, the spray of black hair that dusted the back of it, the way the veins tracked like rivers across its landscape, the way the knuckles rose and dipped, scarred and calloused from years of fighting. Bruised with experience.

“Why do you do this to yourself?” She ran her thumb across those knuckles, unable to resist, unable to remain aloof in the feel of him.

In the memory of him—young and charming and handsome, with the world at his feet—tempting her like nothing else.

Nothing else, but freedom.

She shivered in the cool room, her gaze moving to the fire, where the flames he’d stoked had died away to a quiet ember. She stood and moved to add another log to the hearth, stirring the coals to raise the fire. Once golden flames licked and danced again, she returned to him, staring down at him arms akimbo, and took a moment to speak to him, finding the act much easier with his accusing eyes closed. “If you hadn’t threatened me, we would not be in this position. If you’d simply agreed to my trade, you’d be conscious. And I’d not feel so guilty.”

He did not reply.

“Yes, I left you holding the guilt for my death.”

And still nothing.

“But I swear I did not mean it to go the way I did. The whole thing got away from me.”

Yet still she’d run.

“If you knew why I did it—”

His chest rose in a long, even breath.

“Why I returned—”

And fell.

If he knew, he’d still be furious. She sighed. “Well. Here we are. And I am tired of running.”

No answer.

“I shan’t run now.”

It seemed important to say it. Perhaps because there was a part of her—a very sane and intelligent part of her—that wished to run. That wished to leave him here on his cold, hard floor, and escape as she had so many years ago.

But there was another part of her—not so sane, and not so intelligent—that knew that it was time for her penance. And that if she played her cards right, she could get what she wanted in the bargain.

“Assuming you negotiate.”

She turned to the sideboard, where the day’s paper sat, unread. She wondered if he were the kind of man who read his news each day. If he were the kind of man who cared about the world.

Guilt flared, and she pushed it away.

She tore the sheet of newsprint in half, then searched the drawers in the room until she found what she was looking for—a pot of ink and a quill. She scrawled a note, haphazardly waving the wet ink in the air as she returned to him, still as a corpse.

Extracting a hairpin, she crouched beside him again. “No blood this time,” she whispered to him. “I hope you’ll notice that.”

Still, he slept.

She pinned the note to his chest, reached into his boot to extract her knife, and made to leave.

Except she couldn’t.

At the door, she turned back, noting the chill in the room. She couldn’t leave him like this. He’d catch a death of cold. On a chair in the corner, there was a green and black tartan. It was the least she could do.

She had drugged the man, after all.

She was across the room and had the blanket in her hands before she could change her mind. She spread it across him, tucking it around his body carefully, trying not to notice the size of him. The way he exuded warmth and the tempting scent of clove and thyme. The memory of him. The now of him.

Failing.

“I’m sorry,” she whispered.

And then she left.

Chapter 3

He dreamed of the ballroom at Whitefawn Abbey, gleaming sun-bright in the shade of a thousand candles and the sheen of silks and satins in a myriad of color.

The room belied the darkness that lurked beyond the enormous windows overlooking the massive gardens of the Devonshire estate—the country seat of the Duke of Lamont.

His estate.

He descended the wide marble stairs to the ballroom floor, where a crush of bodies writhed in time to the orchestra situated behind a wall of greenery at the far end of the room. The heat of the revelers overwhelmed him as he made his way through the throngs, pressing against him, pulsing with laughter and sighs, hands reaching for him, touching, grasping. Wide smiles and unintelligible words beckoned him deeper into the mass of people—welcoming him into its center.

Home.

There was a glass in his hand; he lifted it to his lips, the cool stream of champagne quenching the thirst he hadn’t noticed before, but was now nearly unbearable. He lowered the glass, letting it fall into nothingness as a beautiful woman turned and stepped into his arms.

“Your Grace.” The title echoed through him, coming on a wave of pleasure.

They danced.

The steps came from distant memory, a slow, spinning eternity of long-forgotten skill. The woman in his arms was all warmth, tall enough to make him a proper match, and curved enough to fit his long arms.

The music swelled, and still they danced, turning again and again, the sea of faces in the ballroom fading into blackness—the walls of the room falling away as he was distracted by a sudden, heavy weight on his sleeve. He turned his attention to his forearm, wrapped in black wool, pristine but for a sixpence-sized white spot.

Wax, fallen from the chandeliers overhead.

As he watched, the spot liquefied, spreading across his coat sleeve in a thread of molten honey. The woman in his arms reached for the liquid—her long, delicate fingers stroking along the fabric, her touch spreading fire as it crept toward the spot, hot wax coating her fingertips before she turned them up to his gaze.

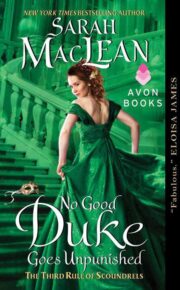

"No Good Duke Goes Unpunished" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "No Good Duke Goes Unpunished". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "No Good Duke Goes Unpunished" друзьям в соцсетях.