He was back to being his smiling, charming, agreeable self, but there was something off about the performance. For it was a performance, a very good one, in a role Nick adopted as easily as a second skin, but a performance nonetheless.

“Let’s start with bacon and eggs, toast with butter, and some of that chocolate,” Leah replied. “What will you be having?”

“All of the above.” Nick filled a plate for her, the portions generous but reasonable. “And some ham, and an orange or two, as well as the inevitable cup or three of tea.”

Leah built her breakfast into a sandwich.

“I take it,” she began between bites, “we shared this bed last night to create the appearance of consummating the marriage?” Her tone was casual, but she had the sense it took Nick a heartbeat or so to comprehend the substance of the question.

“Just so,” he said, studying the chocolate pot. “I trust my staff, but they do gossip, and Wilton can hire spies as well as the next person can. I wouldn’t want Wilton using any doubts to his advantage.”

“If I am asked,” Leah said, pausing in her consumption of the sandwich, “I can honestly say I made love with my husband.”

He bristled beside her, the chocolate pot returning to the tray with a sharp little clink. “Meaning?”

“Aaron Frommer assured me he was my husband in fact,” Leah said. “I made love with him, or consummated the marriage, in the necessary fashion.” She took a sip of her chocolate, keeping her expression placid. “I think every marriage takes some getting used to, just like the first time you ride a new horse or sail a new boat. I will not render all you’ve done for me pointless, Nicholas.”

Her words did not have the intended effect of putting him at ease.

“Nor will I allow my efforts to keep a promise to my father be shown as an empty exercise,” Nick said. “So like the good English folk we are, we will maintain appearances, but, Leah?”

She was Leah this morning, not lovey, not lamb, not sweetheart.

“I hope we can do more than that,” Nick said. “I don’t know how, not when the entire business of the marriage bed is going to be complicated, but please know I want us to be at least cordial.”

“Cordial.” Leah blew out a breath, hating the word. “I can manage cordial, if that’s what you want.”

“I think it for the best. Shall I peel you an orange?”

A cordial damned orange. Despair reached for Leah’s vitals with cold, sticky fingers. The sandwich she’d eaten abruptly sat heavily in her stomach, and the chocolate less comfortably still.

“No, thank you,” she said, feeling her throat constrict again. She didn’t cry, as a rule, not when Wilton insulted her before guests, not when her brothers lectured her about finding a husband, not when Emily was thoughtlessly cruel in her parroting of Wilton’s positions and sermons and criticisms.

She hadn’t cried when her mother died, hadn’t cried when her father warned her Hellerington would offer for her.

If she cried now, Nick would hold her and stroke her back gently and murmur comforting platitudes, all the while oblivious to the fact that he was breaking her heart with his very kindness.

“I suppose our dressing rooms connect?” Leah asked, her voice convincingly even.

“They do,” Nick said, watching her from the corner of his eye as he buttered a scone. “And you have a sitting room between your bedroom and the corridor, though I do not. I had my bedroom redesigned to encompass my sitting room as well.”

Always helpful to know the architecture of one’s husband’s rooms.

“I think I’ll find my things, then.” Leah tossed back the covers and threw her legs over the side of the bed. “I can’t very well review the staff in your shirt.”

She managed to get free of the room without facing him. The next challenge was closing two doors quietly, calmly, and then the third challenge—barely any challenge at all for her—was to sob out her heartbreak without making a single sound.

Thirteen

When Nick knocked on her door, Leah was dressed, thank the gods, and sitting at a vanity, plaiting her long hair. He watched in silence as she wound the coil at the back of her neck, jabbed pins into it, then rose, a faint smile on her face, making her look tidy, capable, and self-contained.

Just as she’d looked when he’d first met her, when she’d been steeling herself for the prospect of marriage to Hellerington.

“Are you sorry you married me?” The question came out of Nick’s mouth without his willing it into words, and he saw Leah was as surprised by it as he was.

“I am not,” Leah said at length. “Not yet. I think in any marriage there are moments when husband or wife or both succumb to regrets, or second thoughts, but you were very clear on what you offered, Nicholas, and what you did not. I am not at all sorry to be free of my father.”

“That’s… good.” What had he expected her to say? Leah wasn’t vicious, and she’d had few real options. “May I escort you downstairs?”

“Of course.” Leah smiled at him, but her smile was tentative, and Nick’s silence as he led her through the house was wary, and their marriage had indeed begun the way Nick intended it to go.

He pushed that sour thought aside as he introduced Leah to each maid and footman, the senior staff, and the kitchen help. From there, they moved to the stable yard, where the stable boys, grooms, and gardeners presented themselves. When the staff had dispersed, Nick led Leah through the gardens, where the tulips were losing their petals, the daffodils were but a memory, and a single iris was heralding the next wave of color on the garden’s schedule.

On a hard bench in the spring sunshine, they decided to tarry for two weeks at Clover Down before presenting themselves at Belle Maison. The earl had sent felicitations on the occasion of Nick’s nuptials, and yet Nick felt an urgency to return to his father’s side.

“He has asked you to join him at Belle Maison?” Leah’s hand was still curled over Nick’s arm, though they sat side by side.

“He has not, and he has told me on several occasions not to lay about the place, long-faced and restless, waiting for him to die. He’s sent my sisters off to various friends and relatives, all except Nita, that is. George and Dolph are similarly entertained, and Beckman is off to Portsmouth to see to my grandmother’s neglected pile.”

“What does Nita say?”

“I hadn’t thought to ask her. I’ll send her a note today, but I think I should also consult with my wife. How do you feel about going to the family seat when death hangs over it?”

“I have no strong feelings one way or the other,” Leah said. “When your father dies, there will be a great deal to manage, and I suspect Nita will appreciate some help then. It might be easier to help if everything were not a case of first impression for me.”

“True,” Nick said, realizing he hadn’t thought matters through from the most practical angle—the angle the women would be left to deal with when Bellefonte went to his reward.

“Two weeks then,” Leah said, “and you’d best let Nita know that as well. We’ll likely leave here before the neighbors start to call, and that might be a good thing.”

Which meant what? Nick didn’t dwell on her comment, but instead drew her to her feet.

“I’ve something I want to show you.”

“I am at your disposal, Nicholas.”

As they made their way through the stables, the feed room, and the saddle room, to a space tucked against the back wall of the barn, Nick reflected that he liked it better when she called him Husband.

“This is a woodworking shop,” Leah said, scanning the tools hung neatly along the walls and the wood stored and organized by size along another. “This is yours?”

“It is. I have one in the mews in Town, and another at Belle Maison.”

“Your hands.” Leah picked up Nick’s bare hand and peered at it. “I’ve wondered what all the little nicks and scratches are from, and this is why you have them, isn’t it?”

“Mostly.” Nick eased his fingers from hers. “I like to make birdhouses.” He pulled a bound leather journal down from a high shelf. “I can show you some of my designs, if you like. You take the stool.” He pulled it up, and Leah had to scramble a little to take her seat. Everything in the room was scaled to Nick’s size—the stool, the workbench, the drafting table, even some of the tools were proportioned to fit Nick’s hands.

And yet, she looked as if she’d been made to fit in this room with him, on this fine mild morning, sharing a little of himself he hadn’t shown to anyone else.

“This is one I made for my stepmother,” Nick began, opening the book. He’d drawn sketches, and then colored illustrations all over the pages. She studied each one, asking questions as if birdhouses mattered.

“This is lovely.” She traced the lines of the birdhouse on the page. “It looks like a garden house, a little hanging gazebo, with trellises and flower boxes. How could you even see to make such things?”

“I wear magnifying spectacles,” Nick said. “The next one was for my papa, though a birdhouse is hardly a manly sort of present. I was eight, though, and had found my first personal passion.”

“Eight is a passionate age,” Leah murmured as she followed his castle with a finger. “Was this for your papa?”

“I only had illustrations in my storybooks to go by, but it was my version of Arthur’s castle. My father loomed in my awareness with all the power and mystery of the legendary king, of course.” And now his father lay dying, and Nick’s birdhouse had weathered to a uniform gray where it hung outside the earl’s bedroom window.

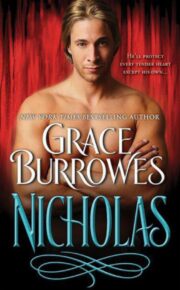

"Nicholas: Lord of Secrets" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Nicholas: Lord of Secrets". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Nicholas: Lord of Secrets" друзьям в соцсетях.