“Tonia was persisting her way into beds when I was just a sprout. Tumble all you like, and give her my regards.”

“I don’t suppose the occasion will arise, as it were.” Val shifted the mood of the piece he was concocting, from playful and light to sweet and soothing. “What troubles you, Nicholas?”

“I wish I knew.” Nick lowered himself beside Val on the piano bench. “What are you playing?”

Val shrugged. “Just notes. You may chime in, I’ll stay below high G.”

“Shameless.” Nick sipped at his drink. “Now you are attempting to trifle with me.”

“Dodging,” Val murmured, “prevaricating, weaseling…”

“I think I am more distracted to be away from Leah than to be away from my usual consorts. I’ll want to leave early tomorrow,” Nick said, rising from the bench. “You’re welcome to sleep in and follow with the coach. I’ve no idea what time Ethan will rise, but I plan to head out at first light.”

“Why?” Val brought his piece to a gentle close and rose from the bench, rubbing his backside with both hands. “London isn’t going anywhere, and you should at least eat and rest before making a journey.”

As if he’d be able to sleep or have any interest in food.

“I am to meet Leah tomorrow afternoon in the park. She’s promised me an answer to my proposal.”

Val left off rubbing his delicate fundament. “Are you more concerned she’ll have you, or reject you?”

And why did Valentine choose now to focus on something other than his music? “God help me, Val, I do not know. I simply do not know, but in my gut, I cannot like that I let her return to Town without one of us to keep an eye on her.”

“Lady Warne will man the crow’s nest,” Val reminded him, crossing to the sideboard, “and Darius and Trenton Lindsey can spike Wilton’s cannon for a day or two. Speaking of Darius…”

“Yes?”

“Have you ever seen such a collection of misfits as he has staffing his estate?” Val poured a half portion of brandy into Nick’s glass, and a full measure for himself. “I hadn’t pegged him as the charitable sort,” Val went on. “Those females on his arm suggest he’s more the type to play hard and fast.”

“I tried to tell him Blanche Cowell would eat him alive, but he merely laughed.” Nick frowned in thought. “It wasn’t a happy laugh, either, Val. At first I thought he was simply being foolish, but I do not take him for a fool upon closer inspection.”

“Can’t his brother talk sense into him?”

“Amherst is up to his ears in small children, and both brothers fret over Leah.”

“Which brings the total to three,” Val said, “because you fret over her too.”

“I do,” Nick conceded, though fret was too mild a word for the roiling panic in his gut. He was tempted to ride out with the moonrise, so intense was his unease. “I’m going upstairs to pack.”

“I’ll probably see you back in Town, then, because there’s more I need to say to my muse tonight, and she to me, I hope.” Val sat back down on the piano bench. “May I assume the hospitality of your town house is yet available to me?”

“You may,” Nick assured him. “In fact, I will insist on it, if you like. Your company…”

“Yes?” Val paused and glanced over his shoulder.

“I’ve enjoyed your company. Even if you do make a great lot of noise at all hours.”

“Love you too.” Val blew him a kiss then brought his fingers crashing down on a resounding chord that heralded the introduction to some rousing Beethoven, the title of which, Nick could not for the life of him recall.

Ethan watched as his father was assisted into a voluminous blue velvet dressing gown. The color of the robe accented the degree to which age had leached the brilliance from the blue of the earl’s eyes, and the way it hung loosely on him pointed up how much weight and muscle a once-impressive man had given up.

“Are you going to stand there gawking,” Bellefonte asked when he’d batted his manservant away, “or come sit in the light where I can pretend to see you?”

“I’ll stand,” Ethan said, but he moved closer, understanding his father was constitutionally incapable of asking for consideration.

“Suit your arrogant, silly self.” The earl balanced himself carefully on the desk and slowly lowered himself onto his favorite chair, landing with a soft plop and a sigh. “Now then, why have you come here, robbing me of my slumbers, when we both know we’ll end up yelling and wishing this might have kept for later?”

“You are running out of laters,” Ethan said, trying to keep his tone brisk. “One must accommodate this inconvenience.”

The earl grinned, making his drawn features look skeletal. “So accommodate, and tell me why you’ve come back. I know you’ve been lurking about the place for the past couple of days. Nita has been looking like the cat in the cream to have you underfoot.”

“Matters between you and me need further resolution.”

“You want to bellow and strut and reel with righteousness?” The earl waved a veined hand. “Well, have at it. I can’t hear or see to speak of, so you’ll only be wearing yourself out, but I suppose you’re entitled.”

“Why would I be entitled?” Ethan pressed, the injured boy in him unwilling to give up his due.

The earl met his eyes squarely. “Because, lad, I made grievous, compound mistakes with you, for which I am sorry. There, can we dispense with the tantrum now?”

Ethan lifted an eyebrow. “That is a declaration of remorse, which does not quite rise to the level of an apology, but no matter. I’ve a modicum of remorse of my own.”

A large modicum, if there was such a thing.

“Oh?” The earl’s tone was a masterpiece of lack of interest, but his aged body sat slightly forward, and his eyes tracked Ethan’s expression like a sinner eyed salvation.

“Oh.” Ethan lowered himself into a chair across the desk from the old man and crossed his ankle over his knee. “Their names are Jeremiah and Joshua, and they are your grandsons, born to me and my late wife, five and six years ago.”

The words started up that damnable ache in Ethan’s throat. The boys would not care that the earl was old and skinny and grumpy. They would love him for the stories he told and his sly, irreverent humor.

They would have loved him.

“No matter my quarrels with you,” Ethan said more quietly, “I should not have kept your only grandsons a secret from you. To do so was to commit a version of the same folly you visited on me when you sent me away.”

For long, silent moments the earl said nothing, merely held his peace and kept his head down. Were he a younger man, a healthier man, Ethan knew he’d be indulging in a tantrum, roaring and reeling and making the servants shudder with his outrage. But he was old, frail, dying.

“I am too damned tired to rise from this chair for something as petty as a display of pique, which would impress you not one bit. Have you miniatures?” the earl asked when he finally met Ethan’s eyes again. Silently, Ethan passed two gold-backed miniatures across the desk, then slid a candle nearer to the center of the desk as the earl peered at the likenesses.

“Going to have your hands full with these two,” the earl said with relish. “They have your stubborn chin, Ethan, and the same light of mischief in their eyes you used to sport. Tell me about them.”

When the earl ran out of energy to ask further questions, he sat back, still studying the little paintings.

“I’m glad you told me,” he said at length. “If Della or Nick knew, they kept your confidences.”

“Nick did not know.”

The earl nodded. “Good of you.” He pushed the miniatures back across the desk, straightening with effort.

“Keep them,” Ethan said gently, his eyes saying what they both knew: It was a loan, to be redeemed after the earl’s death.

“Believe I shall,” the earl said. “And I shall extract a price for guarding them for you.”

“Oh, of course.” Ethan felt humor and an oddly welcome respect for his father’s wiliness. “Name your price.”

“Your brother informs me of his intent to ask for this Lindsey girl,” the earl began, all paternal nonchalance. “Will she do?”

That Bellefonte would seek this information from Ethan was touching. That Ethan would provide it, proof the age of miracles had not entirely ended.

“I like her,” Ethan said. “More to the point, she likes Nick and doesn’t view him as just a means to a title. He doesn’t scare her or awe her or sway her with his charm.”

The earl frowned. “And Nick? Why is he choosing this one, when her past is checkered, she’s not young, and he can’t dazzle her with his usual weapons?”

“I think he trusts her. Trusts she will be grateful enough for his protection to keep her vows and take his interests to heart.”

“So she’s honorable,” the earl concluded. “That will have to do, but, Ethan?”

“Sir?”

“I fear in my dotage, or perhaps in anticipation of an interview with St. Peter, I am growing dithery. I have pushed your brother mercilessly to find a bride before I die, when I myself did not marry until I was considerably older than Nick is now.”

“You were a younger son.” The defense came out unbidden, though it was the simple truth.

“And Nick has three other brothers, though we can’t really count on George to contribute sons to the House of Haddonfield, can we?” the earl groused. “I did not have to demand so vociferously that my heir take a bride, and now that Nick’s marriage is close at hand, I am wishing Nick had chosen for himself, not for me.”

And thus, the ground became boggy with conflicting loyalties. “I don’t think Nick regards himself as very promising husband material. Had you not cornered him with a promise, I doubt he would have chosen any bride at all.”

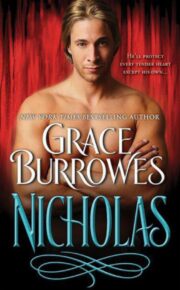

"Nicholas: Lord of Secrets" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Nicholas: Lord of Secrets". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Nicholas: Lord of Secrets" друзьям в соцсетях.