But while to her, love and lovemaking were entwined into one experience, the same wasn’t true for her husband. He hadn’t loved any of those other women any more than he loved her. She feared more than anything the most he would ever be able to offer her would be fondness—however sincere—and the carnal offerings of his body. The same thing he’d offered those other women before their marriage. It wasn’t enough, but if she wanted a baby within the legal bonds of marriage, she had to find a way to come to terms.

She took his hand, climbed onto the sled, and sat.

A flush rose into her cheeks at the easy familiarity of settling so intimately against him, of the sensation of his muscular legs bracketing her safely in place and his warm chest against her back. She tucked her skirts underneath her legs.

“Wrap your arms around my legs and hold on tight.” Sophia did as Claxton instructed, his roughened voice in her ear. His arm came across her abdomen, a solid band of wool-covered muscle.

“Are you ready?” he asked quietly. “You know that once we go over the edge, there’s no turning back.”

“That’s what I’m afraid of.”

“Don’t be.”

At his encouragement, the boy gave them a running push. The blades swooshed over the snow, and at the precipice the sled tilted downward—

Cold air streamed against her face, blowing Sophia’s hair free of her hat. Faster. The sled rocked and rattled as the landscape flew past. Faster! A wild, billowing pleasure spiraled up inside her, the purest sensation of joy, returning her, for the briefest moment, to the happiest days of her youth when her heart carried no fear or premonition of hurt or tragedy. She laughed, then screamed, as Claxton held her tight, his face pressed close beside hers. His laughter rumbled against her back.

Sophia regretted when all too quickly they arrived at the bottom. The sled bumped and skidded to an eventual stop. The euphoria in her chest calmed, and when the boy bounded down behind them to return the duke’s hat and to reclaim his sled, she almost begged them both for another turn at the hill. Instead she remained quiet. Dragging his sled, the boy returned to the top, where his friends cheered.

Sophia straightened her redingote and laughed. “I feared that rickety thing would fall to pieces beneath us. It shook and rattled so!”

“You enjoyed it then.” Eyes bright, with his hair blown straight back from his face, he looked very much in his element, like a Russian prince, alive and glorious, against the backdrop of winter.

“Yes. Oh yes,” she exclaimed. “Thank you for taking me down.”

With his hand at the small of her back, he led her toward the sledge, their boots crunching over the snow. Fat, fluffy snowflakes fell all around them, and the cold worked its way through the soles of her boots and through her clothing. She shivered.

“You’re cold.” He wrapped an arm around her shoulders, and with a twist of his other, he removed the scarf from his own neck and draped it round hers. “I apologize. I shouldn’t have pressed you to—”

“No,” she interrupted. “The best sort of cold. What fun! And I saw what you did up there.”

She glanced at his profile.

“What is that?” he asked, his cheeks ruddy and handsome against the stark white background of the hillside. The wind ruffled his hair. She avoided looking at his lips in a failed effort to forget their passionate embraces in the kitchen.

“That boy,” she said. “Quite different from the others, with threadbare clothes and his boots in pieces. You made sure to use his sled, the most dubious of the lot, and gave him a half crown.”

“A half crown?” He glanced down at her from beneath dark lashes. “Surely not. Only a shilling.”

She pinched his sleeve. “A half crown, Claxton.”

“Purely by mistake.” He returned his hat to his head. “He was merely the closest and most eager.”

“I don’t believe you.”

His eyes burned into hers with a sudden flare of intensity. “Is it so difficult to believe there is something good inside me?”

“No, Claxton,” she answered softly. “Not at all.”

A slight pause followed.

“It is almost Christmas,” he said, jerking his chin aside and peering out over the village. “Perhaps he will purchase new shoes or a coat. But more likely, I expect, he will feed his family.”

He extended his arm, and she grasped it, climbing into the sledge.

After a short ride, they arrived to a darkened Camellia House. A half hour later, a blazing fire and the careful placement of screens vanquished the chill from the great room. There, in the same place where they had partaken of Mrs. Kettle’s wonderful meal, they ate the guinea fowls given to them by the innkeeper the previous day with bread, cheese, and some Christmas beer they’d purchased in the village.

“You play chess, don’t you?” he asked when they were done, setting up a board with the proper pieces. Having removed his coat but not his cravat, he looked very much like a gentleman at ease.

“It has been a long time. I’m certain I’ve forgotten how.” Sophia had intended after the meal to immediately retire to her room.

“Oh, I can’t believe that,” he answered wryly, tilting his head downward and giving her a suspicious eye. “One doesn’t forget how to play chess.”

A familiar heaviness filled her chest, one formed of hurtful memories.

“Perhaps that is true,” she agreed. “It’s just that I was the only one in my family who would play with my father. Neither Daphne nor Clarissa could sit still and pay attention for that long. I haven’t undertaken the game since his death.”

She and her father had shared a love of chess and books and had spent endless hours together, just the two of them. Those were special times that she’d always remember. She could not help but wonder for the thousandth time what he would think of her present difficulties with Claxton. She often yearned for his gentle advice.

“It was a terrible thing, your father’s death,” he said quietly. “Such a terrible stroke of chance.”

“Who would ever have thought? Struck down by a rearing horse. He was always so good with them.”

Claxton remained silent, watching her intently. “You told me, after we first met, but we’ve never talked about how it happened. I always felt that even after two years, the tragedy was still too fresh in your mind. For all of you, including Wolverton, of course. You were there, weren’t you?”

With careful precision she arranged the white pieces on her side of the board, so as to disguise the tremble in her hand. Claxton was right. A stroke of chance. More than three years had passed, but it still felt as if the tragedy had struck just yesterday.

“We’d been outside for hours, watching Daphne and Clarissa at their riding lessons when the skies suddenly darkened.” Sophia paused, remembering the fateful moment that had changed her life and the lives of her mother and sisters forever. “Daphne was having so much fun, she didn’t want to ride in. She told us later that she pretended not to hear us calling. So my father walked out to fetch her. At the first faint rumble of thunder, the animal went skittish. Daphne couldn’t control him, and so my father reached for the harness. That’s when an enormous thunderclap seemed to break the sky in two.” She closed her eyes and exhaled. “It wasn’t Daphne’s fault, but I know she’s never forgiven herself. She’s never ridden again.”

“I’m sorry it happened.” He shook his head. “And just two years after Vinson was lost on the Charybdis.”

“Yes.” Her eyelids lowered at the mention of her elder sibling, who had been lost while on a scientific expedition to the South Seas. “I don’t believe I ever told you, but Havering was on the same expedition. The night Vinson died, Havering was ill and kept to his cabin. It’s why he hovers about so. He believes things would be different had he been there.” She shrugged. “As if he could have done something to stop the sea from claiming my brother.”

“Do you find your cousin, Mr. Kincraig, a worthy heir to your grandfather’s title? I met him only briefly at our engagement ball and had no opportunity to form any sort of opinion as to his true character.”

Inwardly she flinched. Mr. Kincraig was a sore subject in the family since being named heir to the Wolverton title and estates. Until then, he’d been a stranger to them all, and to their dismay, he seemed determined to remain so. The idea that he should take possession of the ancestral history that they had all for so long tended with honor and revered seemed a travesty.

“Hmmm. What a question.” She threw a glance at the ceiling. “Shall I answer with diplomacy or with truth?”

“Always truth with me, Sophia,” he answered solemnly.

She ran her fingertip over the crenellated crown of the king. “He strikes me as arrogant and cold, and he has made no effort whatsoever to seek my grandfather’s good graces or approval or to become part of our family, though we have sought on numerous occasions to make him welcome. He just seems to be waiting. Waiting until—” She could say no more, for a sudden rush of emotion closed her throat. She exhaled miserably and lowered her lashes to conceal her tears. “I just wish my father was still alive and my brother. Once my grandfather is gone, everything will change.”

“Yes, I know.”

“It is his greatest wish that his two remaining granddaughters marry before his death so that their futures are secured.”

“Oh yes.” Claxton sat back in the chair and glared into the fire. The leather of his Hessians glowed like onyx. “Because marriage will solve everything. You and I know that better than anyone.”

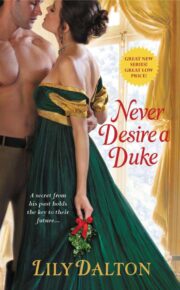

"Never Desire a Duke" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Never Desire a Duke". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Never Desire a Duke" друзьям в соцсетях.