“Theo’s still asleep. I gave Jennifer money, and she walked with Cass and Luke to the Clam Shack.”

Kayla felt feverish. She looked at Jacob. “You’re still here.”

“Val was planning on hashing things out with her hubby,” Jacob said. “Not a scene I wanted to walk in on.”

“Kayla, what happened with the police?” Raoul asked. His diction was thick and deliberate; it sounded like he’d had too much to drink.

Kayla looked out the sliding glass doors. Theo’s Jeep was gone-still up at Great Point. She listened to die ice clink in Raoul’s and Jacob’s glasses, she listened to their molars grind up peanuts. She turned on the kitchen light and this startled them both. Raoul looked at her quizzically with his golden brown eyes. Eyes that, it had always seemed to Kayla, were flooded with sunlight. He was supposed to be her ally, her last resort, her safe place. And yet he’d betrayed her, too. He’d never said a word.

“Jacob?” Kayla said. “Are you on your way home?”

Jacob emptied his drink into his mouth, crunched the ice cubes, and stood up. “Actually, yeah. I was just going.”

“Can you do me a favor?”

“Sure.”

“Can you give me a ride up to Great Point? I have to get Theo’s Jeep. We left it there. God knows what the police will do if they find it.”

“It can wait until morning,” Raoul said.

“No, Raoul,” Kayla said “It can’t.”

“I’ll take you,” Jacob said, “It’s no problem.”

“But it’s dark,” Raoul said. “You’re not going up to Great Point in the dark. Not after last night.”

“I’m getting the Jeep,” she said.

“Okay, fine, then I’ll take you,” Raoul said.

“You’ve been drinking,” Kayla said.

“So has Jacob.”

“It’s on Jacob’s way home,” Kayla said, although Great Point was so out of the way that this could barely be counted as true.

“Relax, man,” Jacob said. “It’s no problem.”

Raoul stuffed his hands into the front pockets of his jeans. Kayla’s heart ached with how much she loved him, and with how sorely he’d disappointed her. The luckiest man she’d ever known, until tonight.

Her third trip to Great Point in twenty-four hours was with Jacob Anderson in his 1991 Bronco that smelled of marijuana. Kayla hadn’t smoked dope since Theo and Jennifer were small children, but she thought of smoking now with longing, especially since her Ativan was gone, especially since she was steeping in her anger.

Her semi-oldies station was on the radio, continuing with the countdown (“Uncle Albert,” “Baba O’Reilly”) and Jacob whistled along. He wasn’t into conversation, and that was fine with her. There weren’t any safe topics tonight, anyway.

When he turned onto Polpis Road, Kayla said, “Do you have a joint?”

He glanced at her. The moon was full, and trees cast shadows on the road.

“Sure.” He flipped open the ashtray and produced a fresh joint. “I didn’t know you smoked. Raoul, he’s so straight…”

“We have four children,” Kayla said. “That’s why he’s straight.”

“Yeah. But you?”

“Ask Val sometime about my wilder days.”

Jacob pressed the cigarette lighter to the tip of the joint. The paper hissed and crinkled as it caught. He inhaled deeply and after he let the smoke go, he held the joint out to her and said, “I always knew there was a wild woman in you somewhere, Kayla.”

She smoked the joint down without responding. What did he mean by that? She concentrated on the dope, the fresh green smell, the promise of it in her lungs. Immediately her head felt lighter, like a balloon. Luke’s purple balloon. She laughed, and it felt wonderful.

They passed the turn for Antoinette’s driveway, but Jacob didn’t slow down or look. Antoinette’s disappearance meant nothing to him except a day off work, a little excitement, his straight boss’s family involved in a small-time scandal. Kayla peered into the dark woods surrounding Antoinette’s driveway and she wondered if they had posted a policeman there for the night. Did the town have that kind of extra staffing? That much money? Did anyone at the police station care except for Detective Simpson? No, she guessed that Officer Johnny Love had gone home at the end of his shift with no one to replace him, and now Antoinette’s house was dark and unprotected.

“Turn around,” Kayla said.

“I thought you wanted to go to Great Point,” Jacob said.

“I do,” she said. “But I want to take a detour. Is that okay with you?”

The air in the car was sweet with smoke. Jacob pulled a U-turn on the spot; the road was completely deserted.

“Where to?” he said.

Kayla directed him to Antoinette’s driveway. The house was still bound up with police tape, but it was unattended, as expected.

“I worked on this house,” Jacob said.

“That’s right,” Kayla said. The front door was closed. Kayla took down the police tape and tried the knob. Locked.

“Shit,” she said.

“You know,” Jacob said, “I remember this woman.” He eyed the front of the house as if Antoinette’s image were projected there. “She is one beautiful lady.”

Kayla sighed, pressed her hand against the wooden panel of the door. “I can’t believe they locked it. How could they lock it without a key? Do you think they found her keys? God, it would be just like the Nantucket police to lock themselves out.”

“I can get in,” Jacob said. He raced back to the Bronco and returned brandishing a T-square. “Looks like a simple measuring device-but wait and see!”

Jacob wedged the ruler into the crack. Kayla was so close to him that she could feel the muscles in his forearm tense. He was a typical man, intent on solving a physical problem. Jacob grunted and voilà-the door popped open.

“You see?” Jacob said.

“Well done,” Kayla said.

Jacob held his arm out. “After you.”

Kayla stepped into the house. Everything had been left as it was-the Norfolk pine lay on its side, dirt spilling from it like blood.

“Antoinette?” Kayla called out. “Antoinette, are you home?”

A clock ticked, moonlight polished the wood floors. Kayla tiptoed down the hall toward the bedroom; broken glass crunched under her feet. The Waterford goblets, smashed.

“Antoinette?”

Antoinette’s bed was mounded with enough black clothing for a month of funerals. The drawers of the dresser had been emptied; the Tiffany lamp on top of the dresser had a crack in its milky glass. It was Theo, Kayla reminded herself. Theo had done this.

As she stepped into the bathroom, someone grabbed her. Kayla screamed. Then she felt Jacob’s face against the back of her neck. He wrapped his arms around her waist and lifted her up. Kayla screamed again. As she struggled to free herself of Jacob’s grip, he lost his balance and the two of them tumbled to the ground. Kayla conked her head on the foot of the bed.

“Ouch!” she said. She started laughing. “You clown!”

Jacob held her around the waist. “Why did we come here?” he asked. “You don’t think Antoinette is here?”

“No,” Kayla said. “I just wanted to look around. I thought maybe if I looked around, things would start to make sense.”

“Some things don’t make any sense.” Jacob said this in the most off-handed way; it was a sentence without any thought behind it, but it rang true in Kayla’s head. Some things didn’t make any sense. Her child having sex with her best friend. Val turning Kayla in to the police. Antoinette dancing into the water.

Jacob rested his hand on the curve just above her hip. Kayla felt heat rise off her body; she was simmering, a cauldron of water ready to boil. She couldn’t find a place inside her to contain her anger-it was too wild, too chaotic. Jacob lay behind her, he growled in her ear. To be funny-but Kayla was overcome with a desire to upset the system. She recalled Val’s words from early that morning. I’d like to do something drastic, something dangerous.

“Jacob?” she said.

He squeezed her in response.

“We should go.”

They smoked the rest of the joint, and by the time they reached the Wauwinet gatehouse, Kayla was hopelessly stoned. She saw the pay phone she had used to call Raoul, then the police, and she giggled. She thought of Detective Simpson and the way his thin, bloodless lips said the words, “Foul play,” and she giggled. Jacob had a dreamy smile on his face. She wondered if he was thinking what she was thinking. She was thinking about his hand on her waist.

“You should let your tires down,” she said.

He kept driving: past the gatehouse, over the speed bumps, and out onto the path that led to the beach. “We’ll be okay,” he said. “I come out here all the time. On Sundays? Just me and my pole.” He pointed a finger at her. “My fishing pole, that is.”

They lumbered over the dunes to the ocean, and Jacob hit the gas. They flew up the beach, sand spraying from the tires. Because it was Labor Day weekend Kayla figured they might see people barbecuing or enjoying the full moon, but the beach was deserted. Maybe word had spread that someone had drowned. Kayla gazed out at the silver water, the gentle waves. It looked just as it had the night before.

“I can’t believe Antoinette is out there,” she said. “Can you believe it?”

Jacob shook his head. “Man.”

“Does Val ever talk about me, Jacob?” she asked.

“About you? What do you mean?”

“Does she ever say she thinks I’m a good friend or that she likes me, or that I’m someone she can trust?”

“She brings up your name sometimes,” Jacob said. “I mean, I know you two are friends. I knew you were friends when I started seeing her. But I can’t remember anything she’s said, like, specifically.”

Kayla popped the cigarette lighter and lit the roach, smoked it until it was nothing but a tiny piece of charred paper. She flicked it out her window.

“I think Val hates me,” she said. “She might not even realize it, but she does.”

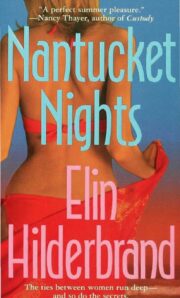

"Nantucket Nights" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Nantucket Nights". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Nantucket Nights" друзьям в соцсетях.