“Where were you?” his mother asked when he got home. She was alone in the kitchen, drying the dinner dishes. “This exploring of yours is getting a little suspect.” She got in his face and sniffed his breath. “Have you been drinking, Theo?”

He stared at his mother. She had a tan and her hair was lighter now that it was summer. When he was a little boy, he always told her how pretty she was. Now, he wanted to slap her.

“Fuck you,” he said. He breezed past her and went up to his room.

Hating his mother gave him focus; he funneled all his anger, his hurt, his frustration into dealing with her. She had been a good person to him his whole life, and he had tried to return the favor. But now he couldn’t look into her face without thinking of the abortion. His child, the only thing he had ever created, ripped from Antoinette’s body and discarded. It was his mother’s fault.

Hating his mother transformed him. His anger swirled around him like a wind, blowing his mother-and father and brother and sisters-away. His mother was afraid of him now, he could see it in her eyes, and that made him hate her more. “Fuck you,” he said. “Please just shut the fuck up, and lose some fucking weight while you’re at it.” He left the house without explanation. He shunned his chores. And on one night when Antoinette had refused to sleep with him, saying it would be best if they cooled things off, he drove his Jeep through his mother’s garden. He threw the Jeep into four-wheel-drive and ran over the puny wire fence she put up to keep rabbits out. He drove back and forth over her herbs and vegetables, breaking zucchini and cucumbers, squashing tomatoes, until every plant was mangled and the garden was marred by deep tire ruts. Fuck you, he thought. Fuck you and your stupid garden.

He kept expecting to be punished. He expected his father, at the very least, to say something. But his parents steered clear; they let him go, his anger trailing behind him like a stench.

As Labor Day approached, Antoinette grew more distant. When he stopped by, she no longer offered him wine, and making love was out of the question. Seeing her still aroused Theo-and once he excused himself to her bathroom, where he masturbated into one of her hand towels. He didn’t care if she knew what he was doing.

When they had a week left, he asked her, “You’re going through with it?”

“Of course, Theo,” she said. Again, on the deck drinking chardonnay but not offering him any. She looked at him as though he were the paper boy. “Don’t you think you should be heading home?”

Then the Friday of Labor Day weekend arrived and Theo knew Antoinette would be going for her annual pilgrimage to Great Point with his mother. Before she left, Theo drove to her house to confront her, because he was sure that spending time with his mother would only convince her further that an abortion was the right thing. He walked into her house without knocking, to show her that he wasn’t timid anymore. He wasn’t the boy that she’d led inside in April. But he checked all the rooms-no Antoinette. Then he heard a car door and peeked out the window. Antoinette climbed out of a taxi. He met her at the door, even though he could see the girl driving the taxi was Sara Poncheau, from school. Antoinette was carrying a plastic tub of lobsters; he took the tub from her and brought it into the kitchen.

“What are you doing here?” Antoinette asked.

“I don’t think you should go tonight,” he said.

She laughed. “That’s not your decision.”

“Still.”

Antoinette poured herself a glass of wine. “Well, I’m going.”

“I’ll have a glass of wine,” Theo said.

She stared at him a second, then took out a goblet and poured him some wine. It was a small, small victory. “You haven’t told me what you’re doing here.”

“Do I need a reason to come by? A man should be able to come by and see his own child when he pleases.”

“There’s no child to see,” Antoinette said. It was true: No sign of pregnancy had manifested itself yet on her body. She was wearing another black outfit: leotard, leggings, Chuck Taylors; and her stomach was pancake flat. “But speaking of one’s child, it just so happens that my daughter is coming tomorrow.”

“Your daughter?” he said. “The one you gave away?”

“That’s the one.”

“How did she find you?” he asked.

Antoinette drank her wine, and Theo felt a surge of protectiveness for his own unborn child inside her, whom he was helpless to protect. Just a cluster of cells,, really-still, with a beating heart, probably, and a sex-and here was Antoinette drinking wine because she didn’t give a shit. Theo took a deep breath.

“The Internet,” Antoinette said. “She hooked up with some group on the Internet that connects children with their birth parents. A representative called me and said Lindsey had been making inquiries and asked if I would let them give her my phone number. With the understanding that she might not use it. But then she did call and we talked. She sounds amazingly normal.”

“I’m surprised you let her call you,” Theo said.

“I surprised myself.”

“But you’re still going to kill our baby?” he said. He grabbed her wrist and her wine sloshed.

“Don’t, Theo.”

He clenched her wrist so tightly that she dropped her glass and it shattered against the kitchen floor. “I’m not going to let you do it,” he said. “I’ll follow you off-island if I have to. I’ll follow you right into the clinic.”

“This isn’t your decision, Theo,” Antoinette said. “God, why don’t you just let me be, boy? Let it go? You’re young, you’ll have plenty of children once you’re older, once you’re married. This isn’t something you want, Theo.”

“You’re not going to kill our child, Antoinette,” he said. “I won’t let you.”

Her voice was icy. “It’s time for you to leave.”

He kissed her hard on the lips, leaving behind a fleck of dill from the cucumber salad he’d eaten at home. He tried to wipe it away, but she swung at him. “Get out!” she said. She bent down to pick up the shards of glass but did so with her eyes trained warily on him, as though she were afraid he might attack her. This made him feel powerful-finally, she noticed him, respected him-but it made him feel sad, too.

“I want you to have our baby,” he said. “I don’t want you to kill it.” He pounded his fist on the kitchen counter; it was granite, cold and unyielding against his hand. He felt tears rise. The thought of the little baby, his baby, helpless against Antoinette’s will drove him mad. How had he gotten here? Eighteen years old, in a dangerous love affair, things spinning so hideously out of his control?

Antoinette held the largest shard of glass out like a weapon, and Theo thought of her cheating husband and how that pain made Antoinette stronger, how it made her think she could do whatever she wanted.

“Antoinette?” he pleaded.

“Leave,” she said.

He returned later, when he knew she would be at the beach with his mother. He ripped her cottage apart. He swept her books off her shelves, he tore the clothes out of her closet and dumped the contents of her dresser drawers onto her bed. He smashed her wine goblets and snapped her fancy candles in half, like he was breaking bones. Before he left, he stole her red-handled hatchet from the woodpile and climbed in his Jeep, sweating, breathing hard, his heart pounding. God, was he angry! He drove to the Ting house. He walked into the living room where he had stood two months before with his father. The walls were up now. Theo swung the hatchet into the fresh plasterboard, leaving huge, garish holes. He could kill someone, he could! He could chop someone’s hands off with that hatchet, someone’s head! He swung the hatchet until the walls were a pile of powdery rubble and his arms were heavy and sore. And then suddenly it was as if his anger had drained, he’d expelled it, and he felt better. When he arrived home, in the minutes before his mother called from the Wauwinet, before Theo heard his father on the phone giving instructions, and before his father told him the news-Antoinette was missing-Theo had actually felt better.

“Baby, baby. Oh, my poor baby.”

His mother led him to her car, saying they would come back for the Jeep, saying they needed to get him home. The woman who was Antoinette but not Antoinette-her daughter, Theo realized-glared at him. A look of hatred. What could he think but that it was Antoinette looking at him? Hating him so much that she had disappeared.

“What am I going to do, Mom?” Theo said.

“You’ll do what the rest of us are doing,” his mother said. “You’ll wait.”

Theo crawled into the backseat of the Trooper, and miraculously, his mother produced a blanket and beach towels. She created a nest for him.

“You must be exhausted,” she said. “Try and sleep, Theo.”

Theo watched the diver surface and shake his head-no, nothing. “But my baby-”

His mother put a hand on his back.

“Lie down,” she said.

He lay down. The towels and blanket smelled faintly of fish. The engine started, and the car bounced over the sand, rocking him to sleep.

Karla

As they drove off Great Point, Lindsey asked Kayla to take her to the airport.

“I’ve seen enough,” Lindsey said.

Kayla was relieved; more than anything, she wanted Lindsey out of her car. No, not more than anything. More than anything, Kayla wanted to travel back in time. She wanted Antoinette safe; she wanted Theo erased from the picture. Theo, her own child, involved with Antoinette. Not Raoul at all, but Theo. Her baby, her first baby, having his own baby with her best friend. So this was Antoinette’s confession. Kayla wanted to vomit, scream, spitfire. She thought of Raoul smoothing the dirt in Antoinette’s driveway. Clearing Theo’s tracks. Because he knew! Kayla was ready to kill someone, but she settled for getting Lindsey Allerton out of her car. Kayla drove to the airport silently, avoiding all thought, the layers of hurt and betrayal that she would eventually have to peel back and examine.

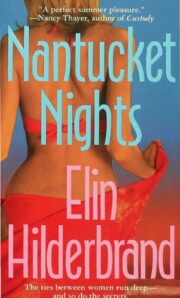

"Nantucket Nights" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Nantucket Nights". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Nantucket Nights" друзьям в соцсетях.