“What did she do in New York?” Theo asked.

“Ballet,” his mother said. She moved on to the next plant and Theo followed. “That’s really all I can tell you.”

“How come?” Theo said. “Is her life, like, classified information?”

His mother ripped his father’s shirt down the middle in a way that seemed almost violent. “Yes,” she said. “It is.”

One evening in mid-June, Theo told Antoinette that he loved her. They had finished making love, and Antoinette was bleeding a little. She had her period.

“Ugh,” she said. “Sorry about that.”

“I don’t mind,” Theo said. “I love you.”

Antoinette disappeared into the bathroom, closing the door. Theo could hear her opening a drawer, rummaging around. He sank his head back into one of Antoinette’s feather pillows. He’d never told a woman that he loved her before. He never said the words, not even to his mother and father. I love you. It was an overused phrase, but that was how he felt, that was who he’d become-someone who loved another person. He felt vulnerable, exposed, scared. He put on his clothes.

“I love you, Antoinette,” he said to the closed door. “Are you listening?”

Oddly enough, it was his father who caught him. One night, the week after the Fourth of July, Theo sat in his Jeep at the end of Antoinette’s driveway. He saw a red Chevy coming from the north, but there were a lot of red Chevys on Nantucket-and besides, his dad was working in Monomoy, which was to the west. But then the driver flashed his lights. Theo threw the Jeep into reverse and backed up ten feet, bent his head, and closed his eyes, praying that the truck would pass. Instead, when he looked up, the red truck was stopped right in front of the driveway, and there was his father, window down, staring at him.

“What are you doing here, Theo?” his father said. “Did your mother send you to get something?”

What could he say? He clawed around for some likely reason for being in Antoinette’s driveway.

“I was out exploring,” he said, “and I made a wrong turn.”

His father stared at him. Theo willed another car to come along and end the issue, but none did. Then his father waved a hand.

“Follow me,” he said. “I want to show you something.”

Theo pulled out behind his father, reviewing the lie in his head. He’d made a wrong turn while exploring. He’d forgotten it was Antoinette’s house until he pulled up, and then, because it looked like she wasn’t home, he’d turned around. Nothing wrong with that.

They drove to Monomoy, to the Ting house, such as it was, barely framed out. Still, the views across the water were incredible. Theo climbed out of the Jeep; he was sweating.

“No wonder you’re never home,” Theo said to his father. “It’s beautiful here.” “It’s beautiful at home,” his dad said. “This is nothing but work.”

“Yeah, well. Huge house.”

“Biggest house on the island.”

“Yeah,” Theo said.

They walked inside-the walls weren’t completely up yet-and headed toward the front of the house where giant windows overlooked the harbor. The wooden floors were littered with tools, nails, an electric sander. The sun was still up above the steeple of the Congregational Church. Seagulls cried. Theo’s hands were shaking.

“So tell me again,” his father said. “What were you doing at Antoinette’s?”

“I made a wrong turn,” Theo said. How long had it been since he’d lied to his father? He couldn’t look his father’s way, but with a view like this, there was no need. Theo focused on the sailboats, which looked like bits of confetti scattered across the water. “I was hunting for a certain dirt road, and I drove up Antoinette’s driveway accidentally.”

“The roads back that way are confusing,” his father said. “I got lost a few times myself when I was building that house.”

It had been two weeks since Theo had told Antoinette he loved her, and she’d said nothing in return. Okay, then, she didn’t love him back. Did he really expect her to?

Theo looked at his father. His mother always said his father was a lucky man. “I’ve been seeing Antoinette,” Theo said. He kicked a nail across the floor. “We’re sleeping together.”

His father’s eyes closed and opened again. Brown eyes flecked with gold, like Theo’s own eyes and the eyes of his brother and sisters. “No,” he said. “I don’t believe you.”

“You have to believe me,” Theo said. “It’s true.”

“What the hell are you telling me?” Theo recognized the expression on his father’s face-he was holding back his anger, keeping himself in check. When Theo’s father was a teenager, he’d flown out of control all the time-started fistfights, punched holes in walls, broke legs off dining room chairs. But not anymore. “Theo,” his father said, in a voice so low Theo could barely hear it. “What’s going on?”

Theo spewed forth the story, an edited version, from the baseball game forward, up to the part where Theo now knew himself to be in love-only instead of the kind of love that made things bright and clear, this kind of love obscured things, confused them. This was the kind of love that was like walking through the dark woods alone, terrifying, unknown.

“I haven’t told anybody else about this,” Theo said. His voice broke. “I want her to love me back, Dad.”

His father put his arm around Theo and squeezed hard. “Trust me when I say you’re in over your head. And what about your mother?”

“What about her?”

His father turned Theo’s face by the chin. “What am I supposed to do? Keep this from her?”

“Yeah,” Theo said. “I mean, you can’t tell her.”

“Well, then, you shouldn’t have told me.”

“Except you’re my father.”

“That’s not going to work, Theo. I’m not getting warm, fuzzy father-son feelings about this conversation. Because what you’re telling me spells danger for you and for your mother. You especially. You’re going to get creamed in this, I promise. Antoinette is too old, too sophisticated, too goddamned complicated. But mostly too old. Do you hear me? Now, I understand wanting to get laid. I understand that part just fine. But not Antoinette.” He put his hands on the windowsill and leaned through the empty window. “What the hell is that woman thinking? You’re just a kid.”

“I’m an adult,” Theo said. “Eighteen, right? Old enough to go to war and all that.”

“It’s wrong,” his father said. “What Antoinette is doing is wrong.”

“It’s not her fault,” Theo said. “Please don’t say anything to Antoinette.”

“Well, it’s over now. I’m making it over.” Theo’s father blew air out his nose, like a bull ready to charge. “You’re forbidden from going over there again.”

“You can’t forbid me to do anything.”

“I sure can. I’m your father.”

“What about you always telling us to make our own choices, to develop our independence? What about that? Was that all bullshit?”

“This isn’t a sound choice, Theo.”

“Just let me deal, okay? I told you because, well, because I needed to tell somebody, and you asked. Whatever, just let me make this mistake if that’s what this is.” He poked his father in the back. “If you tell Mom, I’ll kill you.”

“Don’t threaten me, mister.”

Theo kicked some more nails, then a hammer. What he needed was some help, some understanding. Didn’t his father see that?

“Just forget it,” Theo said. He left the house, got in his Jeep, and headed home.

Theo studied his mother for any sign of change and saw none. So there was that. Either his father respected his decision or he was too afraid to tell Theo’s mother the truth. His father was cold with him, distant, and that hurt because his father wasn’t home that often anyway, and so Theo went from getting a small amount of his father’s attention to none at all. So what could Theo think but, Fuck him? All his father cared about was building some huge house that-according to the principles of 300 Years of Nantucket Architecture-would ruin the character of the island forever.

…

And then, Antoinette missed her period.

She’d been irritable for a few days-if a person who almost never communicated could be called irritable-she didn’t want to be held or kissed. She slapped Theo across the face while they were making love. She pretended like it was an act of passion, except that it hurt, and tears came to Theo’s eyes. When it was over, he said, “Why did you hit me?”

She rolled away from him on the mattress. “Sorry, I was letting out some frustrations.”

“What kind of frustrations?” This was what ate away at him: Antoinette had frustrations and he didn’t even know about it. “Frustrations with me?”

She stood up and looked him over.

“I missed my period.”

“Oh, shit,” he said. They had never used condoms because Theo figured Antoinette would take care of herself-the pill, IUD, menopause for all he knew. “So you think you’re pregnant, then?”

“Well, it’s been a while, but it feels the same.”

“Wait a minute. What feels the same? You’ve been pregnant before?”

“I have a daughter,” Antoinette said. “Or I had a daughter. Twenty years ago.”

“You’re kidding,” Theo said. “You have-a daughter who’s older than me?”

“I gave her up for adoption,” Antoinette said.

“Really?” Theo said. “How come?”

She sighed. “It’s a long story.”

“Tell me,” Theo said. “You never tell me anything.” He touched his cheek where she’d hit him and wondered if she’d left a mark.

She sat down on the edge of the bed and gazed out the window into the woods. “Let me ask you a question,” she said. “Why would you want to know about an old woman’s life? What could it possibly mean to you?”

“I want to know you, Antoinette,” Theo said. “I show up here every day and we… we screw and I don’t know the first thing about you. I don’t know anything about your family, your parents, this daughter. Just tell me about the daughter, okay?”

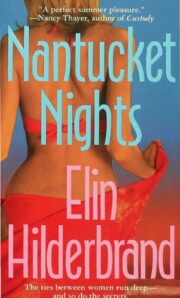

"Nantucket Nights" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Nantucket Nights". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Nantucket Nights" друзьям в соцсетях.