“And you kept it?” he said.

“I hadn’t gotten a gift like that in a long time. Nor have I gotten one since.” She touched his lips and then she kissed him. She tasted smoky and sweet, and the word persimmon came to his mind, though he had never eaten a persimmon, or even seen one, for that matter.

They made love again, and Theo thought of his little boy self on the beach at Tuckernuck, handing the thing most precious to him at that moment to Antoinette, and in thinking about that he felt even more like a man.

He returned again the next day, and the next. At first it was as if his hour with Antoinette were pure fantasy, a visit to another planet where there were no rules, where nothing mattered except their attraction to each other. But then, as more days passed, the opposite became true, and Theo’s life at school and at home turned into the fantasy-a false life, a lie he was living until six o’clock came and he was driving along Polpis Road toward Antoinette’s house.

Baseball season ended. At the awards banquet, held upstairs at Arno’s, Theo was named “Outstanding Infielder.” His parents glowed with pride, and Theo walked to the front of the room as everyone applauded. He took the trophy from Coach Buford and saluted the crowd with two fingers, but his heart wasn’t in it. It was like he was watching himself, or wondering what Antoinette would be thinking if she were watching. He’d won an award at a stupid high school sports banquet where they’d eaten stuffed chicken breasts and ice cream sundaes. So what? He left his trophy on the table on purpose-it was too childish to take home-but his father noticed it and carried it out to the truck for him.

Theo took Gillian Bergey to the junior prom. Her parents belonged to Faraway Island Club, so that was where they ate-in the club dining room that smelled as damp and mildewy as the hull of a ship. They double-dated with Gillian’s friend Sara Poncheau and Sara’s date, a kid named Felipe from Marstons Mills. The rest of the people eating at Faraway Island were older, the age of Theo’s grandparents, and they smiled kindly at the prom couples. Theo sweated in the white dinner jacket he’d rented from Murray’s. Two months earlier, going to the prom with Gillian and eating at the Faraway Island Club had seemed like a good idea. Now he couldn’t wait for it to be over.

During the shrimp cocktail, he asked, “Do you think this club has any black members?”

Felipe, who was Hispanic, said, “Shit, no, man! Don’t you see all these granddaddies looking at me like I’m the busboy?”

Theo nudged Gillian with one of the black plastic shoes that came with his rented tux. “What do you think?”

Gillian was a pale blonde whose skin looked translucent next to the electric blue satin of her dress. Two red circles surfaced on her cheeks. “I have no idea, Theo. I’m sure everyone is welcome.”

“I’m not sure,” Theo said. “I mean, look around. Everyone is white.”

“Everyone on Nantucket is white,” Gillian whispered. “Please don’t make an issue of it. I’ll be embarrassed.”

“Well, I wouldn’t want to embarrass you,” Theo said. He wondered how he had ever found Gillian attractive enough to have sex with. She was so pale you could see her veins. Theo pointed the tail of a shrimp at her. “And FYI, baby doll, not everyone on Nantucket is white.”

Theo danced with Gillian three times at the prom; then he drove her out to the post-party at Jetties Beach. She changed her clothes in the passenger seat of the Jeep, and that would have been the time to make his move-when she was out of her dress but not yet into her shorts and T-shirt-but Theo waited politely outside the Jeep, standing guard, wishing he smoked cigarettes, wishing that he was not at his prom at all, but with Antoinette instead. He took Gillian home without kissing her or feeling her up or anything. Gillian seemed disappointed by that and on Monday she told her girlfriends that he was a jerk, but Theo didn’t care. All he cared about were his afternoons with Antoinette.

In June, after school ended, Theo started his job at Island Airlines, and he fell into the habit of stopping by Antoinette’s on his way home. The only conceivable danger was his mother showing up unannounced. But at that time of day, she was busy with other things: chauffeuring one of the kids, making dinner. She did ask him once, “You’re not still hanging out at the Islander, are you, Theo? After work? You know I don’t like it.”

“Not the Islander,” Theo said. He had a foolproof answer all prepared. “I’ve been exploring the island. Looking at the architecture. I want to study architecture when I go to college, and I thought I might as well get a head start.” He pulled a book out of his backpack titled 300 Years of Nantucket Architecture’, he’d checked it out of the Atheneum with his sister Cassidy’s library card. “So I’ve been driving around, studying.”

His mother thought he was a wonder. She told his father about the book over dinner.

His father perked up when he heard the word architecture, but otherwise seemed distracted. He was busy, especially after he got Ting in June, and Theo understood his father would never notice if he disappeared for an hour each day.

In this way, it was surprisingly easy.

What wasn’t as easy was being in a relationship with an actual woman. With Antoinette.

At first, it was just sex. Seeing her, Theo would get a stubborn erection and Antoinette would make love to him until he cried out, or just plain cried, so grateful was he for the incredible pleasure, a pleasure bordering on pain. Sex made him feel alive, and feeling alive brought on a new fear of death. When he drove, he always fastened his seat belt.

By the time school ended, the sex wasn’t enough. Theo wanted to know Antoinette, he wanted her to talk to him, he wanted her to listen to him. Theo worked his job at the airport-loading luggage onto planes, taking luggage off planes, telling passengers to follow the green walkway-and he became distraught at how little he knew about Antoinette. He looked around her house each night and picked up an object and studied it, hoping for clues. He memorized a few of the titles on her bookshelves and bought them from Mitchell’s Book Corner: Go Down, Moses, by Faulkner, Continental Drift by Russell Banks. He read these books, wondering what they meant to Antoinette, what she gained from them. He didn’t tell her he was reading them.

He started asking her questions at the end of their hour together, simple things.

“What did you do today?”

“What did I Jo?”

“Yeah, you know.” He propped himself on one elbow on her bed. “What do you do in a normal day? You never talk about it. You must have a routine.”

“Oh, Theo,” she said. And she laughed.

“What’s so funny?” he said. “I want to know what you do. Is that so odd? To want to know what my-” He almost said “girlfriend,” but when the word was on his tongue he realized how wrong it would sound. “-my lover does all day?”

“How does it feel,” she asked, “to be an eighteen-year-old with a lover?”

“It feels great,” he said. “But you’re avoiding my question.”

“What question is that?”

“See?” he said. He punched one of her feather pillows like it was someone’s face. He felt himself losing patience. “What the hell do you do all day?”

She got out of bed and put on a plain black cotton sundress with skinny straps.

“I do what everybody else in this world does, Theo. I try to survive.”

“What is that supposed to mean?”

“Okay, look, I eat, I dance, I read, I satiate my sexual desires.”

“Do you want to know what I do?” Theo asked. “Do you want to know how my day at work went?”

Antoinette batted her eyelashes. “How was your day at work, honey?”

“Never mind,” he said.

“Exactly,” she said.

There were funny little things about her. Like, for example, she had no photographs of herself. No pictures of her family. When Theo brought the snapshot of her holding him as a baby, she gazed at it for a long time. “That’s me,” she said finally, as if there had been any doubt.

“Well, yeah,” he said. “How come you don’t have other pictures?”

“Pictures of what?”

“Of yourself.”

She looked truly puzzled. “Why would I have pictures of myself? I already know what I look like.”

“What about your parents, then?” Theo asked. His voice was thick and nervous. It wasn’t fair-she had known him since the day he was born. “Are they still alive?”

“I have no idea,” she said.

“What does that mean?” Theo asked.

“You sure ask a lot of questions,” she said.

He asked a lot of questions but received no answers. Maybe there were no answers, Theo thought. It was as if Antoinette were a mirage, a phantom who had no past and whose likeness couldn’t be captured on film. He tasted her skin, he sniffed under her arms, he tangled his fingers in her coarse, curly hair to reassure himself that she was real.

He was brave enough to bring up Antoinette with his mother only once. Just after school ended, he was helping in the garden and he said, “I saw Antoinette on my way to work today. Riding her bike.”

“Oh, really?” his mother said. She was kneeling in the dirt, staking her tomato plants; it was Theo’s job to hold the plants against the stake while his mother tore strips from one of his father’s old white T-shirts and tied the plants up. “I should call her, I guess.”

Theo stared at the earth, as rich and brown as chocolate cake. “What’s Antoinette’s story, anyway?”

His mother looked up at him. “What do you mean?”

“I don’t know,” Theo said. The sun was hot against the back of his neck. “She’s just so… weird. How did she end up here? Was she born here?”

“No,” his mother said. “She came from New York City the same summer I moved here. We lived together. You know that.”

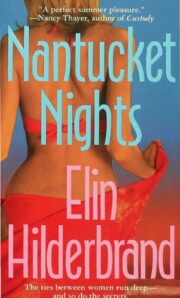

"Nantucket Nights" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Nantucket Nights". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Nantucket Nights" друзьям в соцсетях.