“You’re crazy,” Val said. She ran to the water’s edge. “If they find that bottle, they’re going to think we’re guilty of something.”

Guilty of something. Kayla watched Val wade into the water and retrieve the Methuselah. Kayla hadn’t thrown it very far, and unlike Antoinette, the bottle had washed back to shore, whole and unharmed.

Soon, Great Point was swarming with men. How incongruous, Kayla thought, that their women-only ritual was being invaded by these foreign creatures. A true sign that something was wrong. And what did it say about her that she was relieved, happy even, to see all these men-the men in the coast guard who piloted the search boat, two men on WaveRunners, the men of the police and fire departments who arrived in their Suburbans with their lights flashing, and finally Raoul, who trundled up the beach in his red Chevy? He ran to her like a hero from the movies. Raoul was the luckiest man Kayla had ever met. Just his presence would help.

Paul Henry, a policeman Kayla had known for years, climbed out of one of the Suburbans. Paul was short and wiry, quietly intense. He dressed like a math teacher, or like Mr. Rogers, in cardigan sweaters and canvas sneakers, and he had a crew cut. Kayla asked him once if he’d ever been in the military. Navy, he said-but the crew cut he’d had since he was six years old, and he’d never seen any reason to change it.

“Kayla, Valerie,” Paul said. “Tell me what happened.”

“We were swimming,” Kayla said. “I mean, Val and I were sitting here on the beach and Antoinette danced into the water.”

“She what?”

“She danced into the water. She put her arms out like she was holding a ball, and then she pirouetted into the water. Look, here are her footprints.” Kayla showed him the deep gouges that Antoinette’s toes had left in the sand. “Once she started swimming, we lost track of her.”

Paul Henry pinched his lips together like he’d just eaten a bad clam. “Never, never swim up here without a spotter. At night, no less. It’s irresponsible. Because this is what can happen. This is the danger. Do you see that rip, Kayla?” Paul Henry pointed. “You know better than this. You’ve lived here, what, twenty years? You wouldn’t let your kids do it, and you shouldn’t be doing it yourself.”

“Paul,” Val piped up. “Scolding us now isn’t helping Antoinette.”

Kayla and Val walked with Paul Henry to the water line. The waves lapped over Kayla’s feet, and over the tops of Paul Henry’s canvas sneakers.

Val pointed to an imaginary spot in the dark sea. “I saw her out there.” “And she swam straight out?” Paul asked. “You’re sure?”

“Yes,” Val said.

“I’m not sure,” Kayla said. “Now I can’t remember where I saw her.”

“It was here,” Val said.

“What was she wearing?” Paul Henry asked. “Did she have anything on-a sweatshirt or anything- that might weigh her down?”

“She was nude,” Val said.

“Why in the world were you ladies out here in the middle of the night swimming nude?” Paul Henry said. “What was going on out here?”

“We come every year,” Kayla said. “For Night Swimmers.”

“Night Swimmers?”

“It’s a tradition,” Kayla said. “We’re always careful.”

“Well, not careful enough,” Paul Henry said. “Not tonight.” He radioed the coast guard boat. The boat had a roaming searchlight, there was more talk of the rip current, and they were all silent when someone on the coast guard boat cut through the radio static and said, “With a rip tide like this, a person could be washed out to sea in a matter of minutes.”

Jack Montalbano, the fire chief, approached them. He was a big, hearty Portuguese with a crushing handshake. His wife had died of ovarian cancer the year before, and Kayla hadn’t spoken to him since she’d dropped a roasted chicken off at his house after the funeral.

“Hi, Jack,” she said.

“We’ll find her,” he said, putting his arm around Kayla. “Don’t you worry. The boys will pull her out on the WaveRunners. They always do.”

“Thank you, Jack,” Kayla said. “We know you’re doing the best you can.”

Jack shook hands with Raoul. “Heard you’re working on the Ting house,” Jack said. “Heard that job is so big you have your own phone number for the site.”

Raoul shrugged. “Lots of job sites have their own phone numbers. You know how it is.”

Jack rubbed his hand over his black hair. He was in street clothes: a denim shirt, khaki pants. Jack’s wife, Janey, had been a secretary at the elementary school. She knew every kid’s name by heart, and she had always called when one of Kayla’s kids was sick or in trouble. “No, I don’t. I’m sure as hell not making any money off the wash-ashores the way some folks are. And these Tings, they’re Chinese, right?” Both Jack and Janey had been born and raised on the island; they were warm and kind people, although Jack was known to be close-minded about anyone who wasn’t a native Nantucketer. Round-the-pointers, wash-ashores-this was what he called the summer people and even folks like Kayla and Raoul, who’d lived here for twenty years.

“Does their ethnicity matter?” Raoul said.

“Jack, I want you to find my friend,” Kayla said.

“Rumor on the scanner has it that you ladies were out here fooling around.”

Rumors were everywhere on Nantucket, Kayla thought. Even the police scanner. “Depends what you mean by fooling around.”

“I mean drinking,” Jack said. “Drinking and swimming in waters that would be a challenge for a good swimmer, sober. It’s two o’clock in the morning, Kayla.”

“We’ve been coming out here for twenty years,” Kayla said. “We’re not a bunch of drunk teenagers you can just chastise, Jack.” But her voice sounded whiny and overly defensive, like that of a drunk teenager.

He let a “Chrissake” out under his breath and then stuffed his hands deep in the pockets of his khakis. “It might be best if you all stepped out of the way,” he said. “Maybe you could wait in your car?”

Kayla and Val sat on the front bumper of the Trooper with Raoul between them. Kayla watched Paul Henry pick the empty Methuselah out of the sand. He read the label as he walked over to them.

“You ladies drank all this?”

Kayla huffed. “We’re over twenty-one, Paul.”

“I asked you a question,” Paul said. “I’m your friend, Kayla, but I’m also a policeman and I’m trying to help. Was your friend drinking champagne?”

Kayla threw her hands up. “The rumors are confirmed. We were drinking! Blatantly breaking the open container law!”

Paul scowled at her, unamused. “So you estimate that the woman we’re looking for drank a third of this bottle?”

Kayla looked at Val. Val was asleep with her eyes open. “Not a third. Just a couple of glasses.”

“Two glasses?” he asked.

“Two or three,” Kayla said.

“And how much did you have?” he asked. “This is a huge bottle.”

“Does it matter, Paul?” Raoul asked. “They come out here every year to have some champagne and go for a swim. Celebrate the end of summer. That’s all this was.”

“I’m not insinuating anything else,” Paul said. “But I like to know what I’m dealing with. There’s a big difference between a swimming woman and an intoxicated swimming woman. A big difference.”

A young policeman whom Kayla didn’t recognize approached Paul with a handful of glass shards he’d gathered from the shoreline. The remnants of the champagne glasses.

“Don’t get excited,” Kayla said. “Those are our glasses. I threw them in the water.”

Paul picked up a piece of glass and turned it in the moonlight. “Was this before or after Ms. Riley disappeared?”

“After,” Kayla said.

“So it wasn’t as if you had a fight with Ms. Riley before she decided to go swimming?”

Kayla disliked the way Paul said the words “go swimming.” He said them like they were a euphemism for something else. “No,” she said.

Paul gave the piece of glass back to the young policeman, who was wearing surgical gloves. The coast guard boat moved farther out, and the WaveRunners zipped back and forth closer to shore. Jack Montalbano watched them, smoking a cigarette.

“Why aren’t they diving?” Kayla asked. “Jack, why aren’t they diving?”

“They’re looking above the surface right now,” Jack said. “They’ll dive only if they have to.”

Paul’s walkie-talkie rasped, and Kayla heard the sound of a helicopter.

“Coast guard sent a copter,” Paul Henry said. He sounded impressed.

The coast guard helicopter had a searchlight that swept over the water like the eyes of God. Paul Henry squinted at it, the tendons of his neck stretched tight.

“That baby has a sensor that detects body heat above the water,” he said. “The helicopter will locate her, Kayla. You can bet on it.”

They waited while the helicopter circled the area. At one point it was so far away that Kayla lost track of it, and her stomach turned at the thought of Antoinette all the way out there. Everything keeled to one side like a capsizing boat. Kayla vomited in the sand-the champagne, the lobsters, one stinky, lumpy mess. How had this happened? She wanted to hit reverse, rewind, she wanted to rewrite the way the evening had gone. One moment all of them were safe, the next moment not. Raoul patted her back and gave her a towel to wipe her mouth. Paul Henry handed her a thermos of cold water, which was so unexpectedly beautiful and welcome, tears came to her eyes. She drank nearly the whole thing, letting it drip down her chin. Raoul smoothed her hair.

“Ssshhh, it’s okay.”

But, of course, it wasn’t okay. The helicopter was out of sight, the rescue boat a mere blip on the horizon, and then the WaveRunners pulled onto shore and the riders climbed off, shaking their heads.

“She’s not out there anywhere, boss,” one of the riders told Jack Montalbano. “Do you want us to dive?”

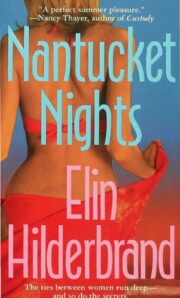

"Nantucket Nights" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Nantucket Nights". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Nantucket Nights" друзьям в соцсетях.