“You think I’m going to drink that.”

He swirled the glass, letting everything mix. “You can toss it out a porthole. Waste of good brandy, though.”

“The fish might enjoy a brandy. It’s a cold, wet night in the Thames.”

“It’s cold up here, too, and nearly as wet.” He carried the glass across to her, being casual, like he didn’t care whether she took it or not. “Drink this and stop being a fool.” His fingers didn’t brush hers when he handed it over. “If you’re not going to trust me, I can always cart you outside and dump you back in the rain. I might even find the exact muddy puddle I picked you out of.”

Empty threats. She preferred them, actually, to the other kind.

She sniffed at the glass. Nothing to smell but brandy and something like smoke. When she took a sip, there was nothing much to taste, either. He was a man of secretive medicines. “What did you say that dusty stuff was?”

“I didn’t. That’s medicinal herbs from the mysterious Orient. Guaranteed to do everything but raise the dead. Can’t possibly hurt you.” The Captain busied himself putting his medical gear away.

Hah. But she took a sip. “I don’t trust medicine much. It’s good brandy, though. My father deals in brandy.” We smuggle it.

Rain tapped on the deck above. That was a good sound. Familiar. She’d spent a hundred nights at sea with the rain overhead. Funny how she felt quiet inside, steady, being with this man. She felt safe. He had practice taking care of his ship and his crew. That’s why his hands were leather, strong and hard. That was from handling ropes and checking cargo and holding onto what he intended to keep. It set prickles of awareness running along her skin, thinking that those hands had undressed her. He’d touched her body, doing that, even if he didn’t admit it. It made sense he wouldn’t want to talk about it.

She looked out the window, past the reflection of the cabin. Rain slapped hard on the glass and ran down in lines.

The light was going. The wharf was empty of carts and horses. Lamps in the warehouse yards cast long, greasy, rippling streaks of light on the stones of the dock. To the left, midriver in the Thames, dozens of ships anchored—schooners and frigates, lighters, barges—all with lanterns, fore and aft, bobbing in the tide. A jagged forest of masts and rigging glowed eerily against the mist.

It’s important what day the ships leave. The sailing dates are half the puzzle. The other half . . . The other half is . . .

And then she didn’t know what the other half of the puzzle was. It made sense a minute ago. Now it didn’t. Maybe this was what it was like, being mad. “I can’t think.”

“Then it’s lucky you don’t have to think.”

“One of those fortunate coincidences.” She wrapped her arms around her knees, looking at the little gray bits floating in the brandy, trying to decide whether she should drink it. It came down to trust, didn’t it? The Captain had risked his neck for her, out there in the streets of London. She’d given him nothing in return but sand and mud in his bed. And she’d made a bargain. She kept bargains. “I haven’t thanked you, have I? For saving my life. I almost remember you doing it.”

“I spend most evenings fishing women out of the deeper puddles in the port area. I consider them legitimate spoil. It doesn’t do any good in the glass, Jess.”

He’d been captain a good, long while. He gave orders like a man used to being obeyed. “I haven’t made up my mind yet.” She yawned, surprising herself.

“I suggest you do so, before you fall asleep again. Or set it aside. You don’t have to worry, you know.” Captain Sebastian’s voice rumbled through her, mild and reassuring, stroking away at the last of the frightened places in her, loosening the knots in her nerves.

He could do anything he wanted to her. Commit any evil. And he didn’t. Here and now, because he was such a dangerous man, she knew she could trust him. Paradox they called that. Looking at it from three or four different angles, she still came up with the same answer.

Wasn’t it lucky her brain worked well enough to tell her that? She took a deep drink of the brandy.

HE saw the exact moment she decided to trust him. She drank the brandy, and she stopped looking like a cat in a sinking lifeboat.

That was good. He was damn sick of scaring her. “Are you still afraid of me?”

“Some. You’re formidable as hell. I suppose you know that.” She tilted her head to one side. “I don’t know how to treat you, Sebastian. I wish you were some pudgy little chap who didn’t scare me to death.”

Alone and hurt, totally at the mercy of a stranger, she could say that and give him a little sidewise grin. Courage to burn, this woman had. “You’ll get used to me.”

He was aroused all over again, seeing that street urchin’s grin. She was going to laugh at him like this, when he had her in bed. She’d tease him and play games under the covers. He’d like that.

Since he wasn’t going to get her underneath him, squirming enthusiastically, anytime soon, he did some walking around, kicking the damp towels together in a pile, rolling up the coastal charts and putting them away in brass tubes, giving his body a chance to cool off.

After a bit, she said, “You carried oranges. I can smell them.”

“First cargo up from the hold.” The Flighty would smell of oranges for a while yet. He didn’t notice, himself. By one of God’s small mercies, the crew stopped smelling cargo after the first day or two. “I sold them on the wharf the morning we docked and was glad to get rid of them. Tricky, delicate cargo.”

“They stow forward and below the waterline, with air moving around them. Then you tear up the water heading home.”

She knew shipping. She had a father or brother or lover who was a shipping clerk or a sailor.

“We leave keel marks on the waves.”

“I can see a picture of it in my mind, how you packed the oranges in. Where they were stowed. How they unloaded. Why do I know so much about your ship?” Panic, just the edge of it, touched her voice. “If I don’t know you, why do I know this ship?”

“There’s lots of ships on the river, Jess.”

She was scaring herself again, thinking she knew Flighty and he was lying to her. So he rolled up a map of the Thames estuary and used it to point to the ships at midriver, the ones they could still see in the gloom, naming them one by one, talking cargoes and ports . . . Canton, Baltimore, the Greek isles, Constantinople. He watched fear eddy and slack inside her. But he’d sold goods all over the Mediterranean. She wasn’t a match for him. He talked and talked, and slowly she let herself be gentled into trusting him. She trusted too easily. Somebody should be taking care of her.

“Feels like I’ve been there, some of those places.” She shifted inside the blankets. He got a brief glimpse of some anatomy he’d been admiring earlier. It was even more tempting, half covered. “Valletta. Crete. Minorca. I can almost see them.”

When she belonged to him, he’d take her to sea and show her Crete and the Greek isles. Why not? She’d take to life shipboard like a seagull. It’d be fine to come on deck and see Jess at the rails, her hair blowing, her bonnet off, and her skin brown from the sun.

Or if she wanted to stay in England, he’d bring the world back to her. He’d drop anchor in London and come home to her and shuck his boots at the door. He’d find her curled up next to the fire, waiting for him. She’d be sleepy, the way she was now, and they’d talk about his trip. Everything he’d seen. He’d bring back baubles from his trading and lay them at her feet. This was a woman he’d enjoy spoiling with presents.

“My brain doesn’t work at all.” She rubbed her hand over her forehead and into her hair to badger her brain better. It was a bad idea. She winced, and her fingers came away red. “I’ve got blood on your blanket. I’m sorry.”

“I have three hundred in the hold. I won’t miss one.”

“A third of a percent. Well within normal shipping loss.”

And she’d got the number right. Mystery after mystery was wrapped around his Cockney sparrow. He was going to enjoy unwrapping them.

She yawned and leaned back against the bulkhead. “I should go home and feed Kedger. Pitney does it if he remembers. But he doesn’t like Kedger. Not really.”

Kedger would be her dog, or a cat. Women liked pets. Maybe when he came home from sea, Jess would be sitting waiting for him with a cat in her lap. Hell, if she didn’t have a cat, he’d buy her one. He liked cats. “Kedger will be fine. Stay with me.”

She was brooding, holding the glass in both hands and looking at the brandy instead of drinking it. “I hate going back to the rooms when Papa’s not there.”

When he sat down next to her, she’d already forgotten to be afraid of him. He cupped her cheek, turning her till he had her whole attention. “Stay with me, Jess. It’s cold out there, and it’s dark, and it’s raining.” In the rookeries, five or six men were waiting for her, hoping for a quiet minute to bash her over the head.

“It is raining.”

“And you’re drunk as a wheelbarrow. Getting there, anyway. ”

“I’m drunk?”

“Three sheets to the wind, as we say at sea. Let’s finish the job.” He tipped up the bottom of her glass and made her drink, hurrying her through the rest of it, getting the medicine into her before she fell asleep. “That’s right. Last drop.”

“Drunk?” She let him have the empty glass. “I can’t think anyway, so it probably doesn’t make much difference. You would not believe how strange it is inside my head.”

“Why don’t you relax and enjoy it.”

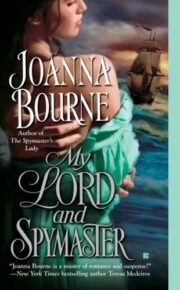

"My Lord and Spymaster" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "My Lord and Spymaster". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "My Lord and Spymaster" друзьям в соцсетях.