He seized me and held me, laughing aloud.

"As you see," he said, "I am out of favor with the Queen."

"But not with me," I said.

"Then I am not unhappy."

He locked the door and it was as though a frenzy seized him. He was mad with desire for me and so was I for him, and although I knew that his anger with the Queen mingled with his need for me, I did not care. I wanted this man. He had haunted my thoughts from the first moment I had seen him riding beside the Queen at her accession; and if his desire for me was in some measure due to her treatment of him, she was part of my need of him too. Even in our moments of extreme ecstasy it was as though she was there with us.

We lay together, knowing full well that it was a dangerous thing to do. Were we to be discovered we could both be ruined, and we did not care; and because our need for each other transcended our fear of the consequences, it heightened our passion, intensified those sensations which I at least—and I think the same applied to him—believed could come to me through no other.

What was this emotion between us? The recognition of two like natures? It was overwhelming desire and passion and not least of our emotions was the awareness of danger. The fact that each of us could risk our future for this encounter carried our ecstasy to even greater heights.

We lay exhausted, yet triumphant in some way. We should neither of us ever forget this experience. We were bound together by it for the rest of our lives and whatever should happen to us we should never forget.

"I shall see you again ere long," he said soberly.

"Yes," I answered.

"This is a fair meeting place."

"Until we are discovered."

"Are you afraid of that?"

"If I were I should count it worthwhile."

I had known he was the man for me as soon as I had seen him.

"You're looking smug, Lettice," said the Queen. "What has happened to make you thus?" "I could not say that anything has, Your Majesty."

"I thought you might be with child again."

"God forbid," I cried in real fear.

"Come, you have but two ... and girls. Walter wants a boy, I know."

"I want a little rest from childbearing, Madam."

She gave me one of her little taps on the arm. "And you're a wife who gets what she wants, I'll warrant."

She was watching me closely. Could she possibly suspect? If she did I should be drummed out of the Court.

Robert remained aloof from her, and although this sometimes angered her, I was sure that she was determined to teach him a lesson. As she had said, her favor was not so locked up in any man that he could dare take advantage of her fondness. Sometimes I thought she was afraid of that potent attractiveness—of which I had firsthand knowledge—and she liked to whip herself into a fury against him to prevent herself falling completely victim to his desires.

I did not see him as often as I should have liked. He did come once or twice unobtrusively to Court and we met and made passionate love in the private room. But I could sense that frustration in him and I knew that what he wanted above all things was not a woman but a crown.

He went to Kenilworth, which he was turning into one of the most magnificent castles in the country. He said that he wished I could go with him and that if I had had no husband we could have married. But I wondered whether he would have talked of marriage if it had not been safe to do so, for I knew that he had not given up hope of marrying the Queen.

At Court his enemies were starting to plot against him. They clearly thought he was in decline. The Duke of Norfolk—a man I found excessively dull—was a particular enemy. Norfolk was a man of little ability. He had strong principles and was weighed down by his admiration for his own ancestry, which he believed— and I suppose he was right in this—was more noble than the Queen's, for the Tudors had sneaked to the throne in a very backdoor manner. Vitally brilliantly clever people they might be, but some of the ancient nobility were deeply conscious of their own families' superiority and none more than Norfolk. Elizabeth was well aware of this and, like her father, ready to nip it in the bud when it appeared, but she could not stop the blossoms flowering in secret. Poor Norfolk, he was a man with a sense of duty and tried always to do the right thing, but it invariably seemed the wrong thing ... for Norfolk.

For such a man it was galling to see the rise of Robert to the premier position in the country, which he felt because of his birth belonged to him, and there had been one occasion not very long before this when a quarrel had flared up between Norfolk and Leicester.

There was nothing Elizabeth liked better than to see her favorite men jousting or playing games, which called attention not only to their skill but to their physical perfections. She would sit for hours watching and admiring their handsome bodies; and there was none she had liked to see in action more than Robert.

On this occasion there had been an indoor tennis match and Robert had drawn Norfolk as a partner. Robert was winning, for he had exceptional skill in all sports. I was sitting with the Queen in that lower gallery which Henry VIII had had built for spectators, for he too had excelled at the game and enjoyed being watched.

The Queen had leaned forward. Her eyes had never left Robert, and when he scored a point she had called out "Bravo" while during Norfolk's less frequent successes she was silent, which must have been very depressing for England's premier duke.

The game was so fast that the contestants had become very hot. The Queen seemed to suffer with them, so immersed was she in the play, and she lifted a mockinder—or handkerchief—to wipe her brow. As there was a slight pause in the game and Robert was sweating profusely, he snatched the mockinder from the Queen and mopped his brow with it. It was a natural gesture between people who were very familiar with each other. It was actions like this which gave rise to the stories of their being lovers.

Norfolk, incensed by this act of lese-majesty—and perhaps because he was losing the game and was aware of the royal pleasure in his defeat—lost his temper and shouted: "You impudent dog, sir. How dare you insult the Queen!"

Robert had looked surprised when Norfolk had suddenly lifted his racket as though he would strike him. Robert had caught his arm and twisted it so that Norfolk had called out in pain and dropped the racket.

The Queen had been furious. "How dare you brawl before me?" she had demanded. "My Lord Norfolk must look to it or it may not be only his temper which is lost. How dare you, Sir Norfolk, conduct yourself in such a manner before me?"

Norfolk had bowed and asked leave to retire.

"Retire," the Queen had shouted. "Pray do, and don't come back until I send for you. Methinks you give yourself airs above your station."

It is a dig at his overweening family pride, which she resented as a slur on the Tudors.

"Come, sit beside me, Rob," she had said, "for my Lord Norfolk, knowing himself the loser, has no longer stomach for the game."

Robert, still holding the mockinder, had seated himself beside her, well pleased to have scored over Norfolk, and she took the mockinder from him and smiling had attached it once more to her girdle, implying that the fact that he had used it in no way displeased her.

So it was not to be wondered at that now, when Robert was thought to be in decline, Norfolk headed the long list of his enemies, and it was clear that they were going to exploit the situation to the full.

Attack came from an unexpected quarter and a very unsavory one.

There was a tense atmosphere at Court. The Queen was never happy when Robert was not with her. There could not be any doubt that she loved him; all her emotions concerning him went deep. It had even been obvious in their quarrels how much she was affected by him. I knew that she wanted to call him back to Court, but she was so beleaguered by the marriage question and Robert was growing more and more insistent, that she had to hold him off. If she sent for him it would be a victory for him and she had to make him understand that she called the tune.

I had begun to accept the fact that she was afraid of marriage, although of course the Scottish ambassador had been right when he had declared she wanted to be supreme ruler and share with none.

I felt drawn to her in a way because my thoughts were as full of Robert as hers were and I was watching for his return as hopefully as she was.

Sometimes when I was alone at night I used to contemplate what would happen if we were discovered. Walter would be furious, of course. To hell with Walter! I cared nothing for him. He might divorce me. My parents would be deeply shocked, especially my father. I should be in disgrace. They might even take the children from me. I saw little of them when I was at Court, but they were growing into real people and were beginning to interest me. But chiefly I should have to face the Queen. I used to lie in bed shivering—not only with fear but with a kind of delicious delight. I should like to look into those big tawny eyes and cry: "He has been my lover but never yours. You have a crown and we know he wants that more than anything. I have nothing but myself—yet next to the crown, he wants me. The fact that he has become my lover is a measure of his love for me, for he has dared risk a great deal to do so."

When I was with her I felt less brave. There was that in her which could strike terror into the boldest heart. When I contemplated her fury if we were discovered I wondered what her punishment would be. She would blame me as the seductress, the Jezebel. I had noticed that she always made excuses for Robert.

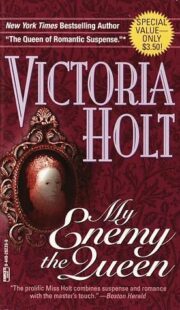

"My Enemy the Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "My Enemy the Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "My Enemy the Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.