"I can see that such a man as Mr Crawford would like to have his own way," replied Mr Norris in a serious tone. "But we cannot all have his same luxury of choice. I envy him that. Most of his fellow men are condemned to self-denial, and an enforced submission to the will of others."

Mary laughed. "I doubt that the nephew of Sir Thomas Bertram can know very much of self-denial. Now, seriously, Mr Norris, what have you ever known of hardship? When have you been prevented from going wherever you chose, whenever the fancy took you? When have you been forced to rely on the kindness of others to supply the necessities of board and lodging?"

She stopped, knowing she had said a great deal too much, and averting her eyes, was unable to see the look on his face as he replied,"Miss Crawford is pleased to remind me of the differences in our situations. But," he said, in a softer accent, "in some matters of great weight, I too have suffered from the want of independence."

"Is this," thought Mary, "meant to refer to Miss Price?" Her embarrassment appeared in an agitated look, his in a rush of colour; and for a few minutes they were both silent; till the distant apparition of Henry promised to save them both from further discomfiture. He met them with great affability, saying that he had returned to the parsonage, and finding Mary still absent, had walked out to meet her. Mr Norris took the first opportunity of consigning Mary to her brother’s care, and when Henry then turned to her and asked what the two of them had been talking of so earnestly, she hardly knew how to answer.

Chapter 4

As she dressed for dinner the following day, Mary struggled to achieve at least the appearance of composure; her brother might make such public shew of his own attachment as he chose, and not care for the consequences; Mary must be more guarded and more circumspect. And now that she was fully apprised of her own feelings, she was apprehensive lest Henry’s discernment or her sister’s shrewd eye might discover the truth; she did not know, in reality, whether it was her brother’s raillery she feared more, or the sisterly concern of Mrs Grant’s warm and affectionate heart.

For the time being, however, Mrs Grant seemed more concerned with the small cares and anxieties of her toilette. "What dreadful hot weather this is!" she said, working away her fan as if for life, as the carriage made its way across the park. "It keeps one in a continual state of inelegance."

"We shall, at least, find the company somewhat enlivened this evening by the presence of another guest," remarked her husband, rather sourly. "A larger group is always preferable — tiny parties force one into constant exertion."

As they approached the Park, they passed close by the stable-yard and coach-house.

"Ha!" cried Henry in delight. "The much-anticipated Rushworth must be here already! You were right, Mary, ’tis a barouche. And a very fine one, at that! Quite as gaudy and ostentatious as I expected. This is much better than I had dared to hope; I anticipate an evening of the keenest enjoyment."

As it was, the parsonage party heard Mr Rushworth before they saw him, for the sound of his voice reached them even as the servant led them across the hall.

"My dear Lady Bertram," he was saying loudly, "the insufferable dilatoriness one endures at their hands! The thousand disappointments and delays to which one is exposed! The trouble that is made over the slightest request, the tricks and stratagems that are employed to avoid the simplest tasks, make one quite despair. Only this morning I decided that blue was quite the wrong colour for the drawing-room and directed the painter that the entire room should be done again in pea-green. One would have thought that I had asked him to undertake one of the labours of Hercules." "For Heaven’s sake, man," said I, "’tis nothing more than a little distemper — no more than half an hour’s work for a great lubberly fellow like you. Go to it, man! You will have it done before dinner-time!" But needless to say, when I left Sotherton two hours ago he was still there, on his hands and knees with a sponge and a pail of water. They have no capacity for diligence, Mrs Norris, no enthusiasm for honest toil!"

"Oh! I can only agree with you, Mr Rushworth," simpered Mrs Norris, "and if he were here, my dear husband would concur most heartily. When we had the dining-parlour at the White House improved, we had to insist that the work was done over three times. I told Mr Norris not to pay them a shilling until we were completely satisfied with the results."

Mr Rushworth was just beginning to commend Mrs Norris’s good management when the Grants and Crawfords made their entrance. When Mary was introduced he addressed her with affected civility, and gave a haughty bow and wave of the hand, which assured Henry, as plainly as words could have done, that he was exactly the coxcomb he had been hoping for. However, the smiles and pleased looks of those standing round him by the fire shewed that many of the family had already formed a completely contrary opinion. Mary soon observed that Miss Bertram looked particularly happy; her countenance had an unusual animation, which was heightened still farther when they went in to dinner and she was seated opposite to their principal guest.

Henry took a place near to Miss Price, but she very pointedly gave her whole attention to Mr Rushworth, who was sitting beside her. With both Miss Bertram and Miss Price claiming a share in his civilities, Mr Rushworth had much to do to satisfy the vanity of both young ladies, but it soon became obvious to Mary, that despite paying the most flattering courtesies on either side, their visitor’s eye was far more often drawn to Maria than to her cousin. Miss Price saw it too; of that there could be no doubt. Her face crimsoned over and she was evidently struggling for composure. Mary saw that she was piqued, and found herself divided between a hope that Miss Price might derive some benefit from such a lesson in humility, and a degree of sympathy she would not have anticipated, had she pondered the question with cool consideration. Accustomed as the young lady was to constant deference and an easy pre-eminence, no-one seemed to have thought it useful to teach her how to govern her temper, or sustain a second place with patience and fortitude.

Of the tumult of Miss Price’s feelings, however, her family seemed perfectly unaware. Mary thought, however, that she observed a look and a smile of consciousness from Miss Bertram, which shewed that she could not but be pleased, she could not but triumph, meeting with such a delightful and unwonted event. Mary wondered what such an unexpected development might lead to, but even her foresight was not equal to imagining what was eventually to ensue.

When the dessert and the wine were arranged, the subject of improving grounds was brought forward again, and Mr Rushworth turned to Henry with all the careless insolence of imaginary superiority. "Knowing something of your reputation, nothing could be so gratifying to me as to hear your opinion of my plans for Sotherton. After all, it is so useful to have one’s genius confirmed by a professional man."

Henry coloured, and said nothing, but Mr Rushworth’s eyes were fixed on the young ladies. "In my opinion it is infinitely better to rely on one’s own genius," he continued, "or, at most, to consult with friends and disinterested advisers, rather than throw the business into the hands of an improver. I had considered engaging Repton. His terms are five guineas a day, you know, which is of course a mere nothing, but in the end I could not see what such a man could possibly devise that I could not do fifty times better myself. How could it be otherwise? I own that he may be blessed with natural taste, but he has no education, none of the instruction that improves the mind and informs the understanding."

Henry’s mortification was apparent, at least to some, and Mr Norris hastened to ask him about his proposals for Mansfield.

"We have all, at one time or another in the last few weeks, attempted to divine your intentions, Crawford, but so far you have always stood firm. But we will not be denied tonight — come, you must let us into the secret. Mrs Grant, Miss Crawford, you must join me in persuading your brother."

Henry laughed, but protested that it would be impossible to do justice to the imagination and invention of his proposals (this with a look of meaning in the direction of Mr Rushworth) without his sketches and drawings shewing the park as it now was, and as it would be after his improvements.

"But surely you can give us some idea?" cried Tom Bertram. "A general picture of what you propose?"

"With Sir Thomas’s permission, I will be happy to do so." Sir Thomas bowing his consent, Henry began his narration; and Mary smiled to see him now the centre of attention, with even Miss Price gazing intently upon him.

"I will begin with the river, or perhaps rivulet is a more apt term; a place such as Mansfield should not be dishonoured by such a thin brook that floods with every shower. No, Mansfield deserves the splendid prospect of an abundant river, majestically flowing. But," he said, turning to his neighbour, "I see a question in Miss Price’s eyes. She is wondering how this is to be done. And the answer is that I propose to build a new weir, a weir that will augment the flow of the river, and create a cascade within view of the house."

There was the greatest amazement at this, and expressions of astonishment and admiration on all sides.

"And yet," he said, smiling, "I have barely begun, and my next scheme is even more ambitious than the first. I will open the prospect at the rear of the house and create a vista that will be the envy of the whole country!"

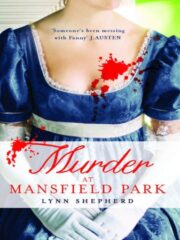

"Murder at Mansfield Park" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Murder at Mansfield Park" друзьям в соцсетях.